eBook - ePub

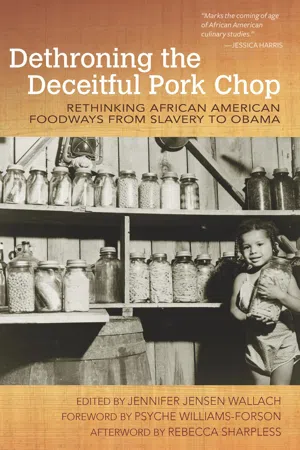

Dethroning the Deceitful Pork Chop

Rethinking African American Foodways from Slavery to Obama

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Dethroning the Deceitful Pork Chop

Rethinking African American Foodways from Slavery to Obama

About this book

2016 Choice Outstanding Academic Title

2017 Association for the Study of Food and Society Award, best edited collection.

The fifteen essays collected in Dethroning the Deceitful Pork Chop utilize a wide variety of methodological perspectives to explore African American food expressions from slavery up through the present. The volume offers fresh insights into a growing field beginning to reach maturity. The contributors demonstrate that throughout time black people have used food practices as a means of overtly resisting white oppression—through techniques like poison, theft, deception, and magic—or more subtly as a way of asserting humanity and ingenuity, revealing both cultural continuity and improvisational finesse. Collectively, the authors complicate generalizations that conflate African American food culture with southern-derived soul food and challenge the tenacious hold that stereotypical black cooks like Aunt Jemima and the depersonalized Mammy have on the American imagination. They survey the abundant but still understudied archives of black food history and establish an ongoing research agenda that should animate American food culture scholarship for years to come.

2017 Association for the Study of Food and Society Award, best edited collection.

The fifteen essays collected in Dethroning the Deceitful Pork Chop utilize a wide variety of methodological perspectives to explore African American food expressions from slavery up through the present. The volume offers fresh insights into a growing field beginning to reach maturity. The contributors demonstrate that throughout time black people have used food practices as a means of overtly resisting white oppression—through techniques like poison, theft, deception, and magic—or more subtly as a way of asserting humanity and ingenuity, revealing both cultural continuity and improvisational finesse. Collectively, the authors complicate generalizations that conflate African American food culture with southern-derived soul food and challenge the tenacious hold that stereotypical black cooks like Aunt Jemima and the depersonalized Mammy have on the American imagination. They survey the abundant but still understudied archives of black food history and establish an ongoing research agenda that should animate American food culture scholarship for years to come.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dethroning the Deceitful Pork Chop by Jennifer Jensen Wallach in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences sociales & Politique publique en matière d'agriculture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Archives

CHAPTER 1

Foodways and Resistance

Cassava, Poison, and Natural Histories in the Early Americas

While sugar is the food with which Africans in the early Americas are most closely associated, and certainly the food whose value as a commodity and consumable outweighed all others, sugar was produced to be consumed elsewhere and not by the people who produced it. Colonial economies depended on other foods, both those indigenous to the Americas and those imported from as far away as the Pacific, to feed the huge population of enslaved Africans who planted, cultivated, harvested, and processed sugarcane.1 Moreover, Africans’ diets were determined to a large degree by planters’ financial concerns and, by the late eighteenth century, their attempts to maintain their labor force without metropolitan oversight. As planter David Collins wrote in his Practical Rules for the Management and Medical Treatment of Negro Slaves, in the Sugar Colonies. By a Professional Planter, “It may be laid down as a principle, susceptible of the clearest demonstration, that every benefit conferred on the slaves, whether in food, or clothing, or rest, must ultimately terminate in the interest of the owner.”2 Planters’ concerns about maintaining control of the slave trade in the face of abolitionist arguments—what Collins called the “interest of the owner”—motivated them to provide slaves with what they deemed to be a regular supply of sustaining food. As Collins noted, food was crucial to maintaining an efficient labor force: “the energy and vigor of an arm depends, next to natural temperament, upon an ample supply of food; therefore, the Planter, who would wish to have his work done with pleasure to himself, and with ease to his slaves, must not abridge them, as is too frequently the case.”3 Far from deriving from concerns about the inhumane conditions of slavery, planters’ interest in Africans’ diets may be traced to their desires to control their slaves and to maintain their profits and access to the slave trade by “ameliorating” the conditions of slavery.

Considering early African American foodways in the context of plantation slavery thus raises a number of epistemological and methodological quandaries. First, the archive containing records of enslaved Africans’ foodways is found in colonial texts whose purpose was not simply to report on the Americas but to justify slavery, to defend planters’ behavior, and to present so-called foreign or exotic peoples and practices to European readers. In particular, as Vivian Nun Halloran points out, there is rarely a “written archive of culinary knowledge” for enslaved Africans before the nineteenth century.4 When African foodways are described in this archive, it is often through a lens shaped by Euro-colonial views and rhetorical practices, elements that supported planters’ attempts to preserve the slave trade by controlling representations of Africans. Second, planters’ interest in controlling Africans’ diets raises the question of how much agency slaves had over their foodways and, more specifically, whether Africans’ pre-existing, Old World agricultural knowledge and practices of consumption influenced what they ate. For example, the recent debates about whether African knowledge of rice was transferred to the Americas, especially in South Carolina, and about the degree to which this knowledge influenced planters have revived questions about the degree to which African practices survived the Middle Passage or were remade in the Caribbean.5 As David Eltis, Philip Morgan, and David Richardson argue in a co-authored article, slaves certainly arrived in Americas with knowledge that was applicable to the forms of agriculture present in the Carolinas and the Caribbean, but “what was basically at issue is who had the power to transform the plantation economy and reorient it to new crops.”6 Planters, they point out, “held the reins of power, experimented keenly, and in essence called the shots,” while the larger Atlantic economy and the supremacy of sugar determined what other crops were cultivated.7

The essay takes these debates as a starting point for its investigation of African and Afro-Caribbean foodways in the British West Indies, as represented in natural histories, a genre employed by European travelers and men of science who collected botanical specimens and recorded their observations in great detail in order to provide their metropolitan audiences with information about the Americas’ flora and fauna. As I explain, natural historians sought to apply principles of “good ordering” to the people, plants, and animals they observed, both by placing them into categories according to their species or use and by extending these categories to rule humans’ behavior.8 Yet, as I argue, this very impulse to rhetorical and material order also makes natural histories into valuable resources that provide insights into Africans’ foodways: specifically, how enslaved peoples employed their knowledge of food as a form of resistance. Africans’ knowledge of uniquely New World foods, particularly cassava, a root that could be processed into flour and that became a major component of slaves’ diets, destabilized the categories with which natural historians sought to order phenomena on plantations, including Africans themselves. These moments of textual disruption show how Africans employed their knowledge of Caribbean foods for both survival and resistance, while also indicating how enslaved Africans influenced the content and the form of colonial texts. My focus on literary or rhetorical evidence of Africans’ foodways in the Caribbean might be productively combined with historical studies of slaves’ provenance and agricultural knowledge to uncover the range of uses to which Africans throughout the Americas put their foodways and to broaden scholars’ understandings of the archives in which accounts of such foodways appear.

Natural Histories and Plantation Slavery

Natural histories were a “scientific discipline, intellectual obsession, and literary form” employed by men of science in Europe and in the Americas and by collectors seeking to gain approval in metropolitan scientific circles.9 They responded to the “explosion of information” produced by travel to and settlement in the Americas, for they offered a form with which writers created a “catalog of nature,” and they allowed travelers and natural philosophers alike “to find techniques for presenting timely accounts of recent discoveries, while also assimilating and organizing a vast, rapidly growing body of reports.”10 They also fed the desire for New World exotica back in Europe, that is, the desire to collect, observe, and possess objects from the Americas, with the goal of displaying one’s wealth and sophistication.11

Often filling several large volumes, natural histories usually began with a preface or introduction describing the writer’s goals and sometimes the conditions under which he collected information and made observations. The history itself was divided into chapters or books, each devoted to the close description of objects in a particular category, usually including air and climate, diseases, animals, vegetables, animals living in water, insects, and so on. These chapters reflected the categories in which natural historians classified flora and fauna, and they likewise elucidated the qualities of individual specimens. A specimen’s place in a category exposed its similarity to and difference from other specimens, in this way illuminating the unique features of that object. Natural historians applied their prior knowledge and education to create these categories, so that while they did devise new names when they encountered plants or animals unknown in Europe, Old World perspectives shaped the ways that they encountered, described, and presented New World phenomena on paper.

As Christopher P. Iannini has pointed out, natural histories and West Indian plantation slavery were inextricably connected in the eighteenth century. Planters sometimes collected specimens for natural historians; others wrote their own natural histories. Moreover, the Caribbean’s lush flora and fauna, extreme weather, and geography attracted the curiosity of many European men of science. Finally, as Iannini writes, natural histories were at the center of debates about slavery: they “emerged as a crucial medium not only for the circulation of natural knowledge among physicians, planters, botanists, gardeners, merchants, and investors but also . . . for assessing the moral significance of colonial slavery as a new and seemingly necessary dimension of modern social and economic life.”12 In particular, natural histories grappled with the ways that plantation slavery confused the category of the “object.” Despite their use of categories to identify and classify objects according to their “place” in natural systems, natural historians found that some objects eluded their categories and that the category of the “thing” itself was far from coherent in the West Indies. Iannini points out that “things” in the Caribbean included not just entities like sugarcane and cockroaches but also chattel slaves, “at once property and person, commodity and laborer, object of study and bearer of knowledge.”13 Indeed, natural historians had to confront the fact that in the West Indies “the boundary between specimen and naturalist, thing and agent, is neither clear nor stable”; for example, the slaves whose commerce and labor drove the West Indian economy were also potential sources of knowledge.14 Even as writers attempted to apply natural historical forms to people as well as to things in the Caribbean, they found that Africans disrupted this order and their categorization as things.

In this chapter, I extend Iannini’s focus on natural historians’ concerns about slave agency by examining the particular dietary practices and culinary knowledge that Africans in Barbados and Jamaica employed both for survival and for resistance. Africans’ practices of consumption existed in tension with both planters’ and natural historians’ attempts to order slaves and their practices. I examine these moments of contradiction and disruption in the context of Africans’ foodways both to explore how Africans’ material practices shaped natural histories’ content and form and to investigate how natural histories represent Africans’ multiple uses for food, including uses antithetical to planters’ and natural historians’ purposes.

Food and Order

Natural histories imposed order on the Caribbean’s natural phenomena by classifying flora, fauna, and, ultimately, people, and this order doubled as a foundation for plantation management. In one of the first English natural histories of the Caribbean, printed in 1657, gentleman and Royalist exile Richard Ligon described observations made during his three years’ stay in Barbados, where he worked as an overseer or plantation manager.15 Ligon arranged the objects he encountered in categories that ordered things by type and by their relation to one another, from food, drink, commodities imported, and commodities exported to buildings and materials with which to build. For example, he commented in his section on food, “The next thing that comes in order, is Drink.”16 And he noted after a discussion of the difficulty of importing butter to Barbados, “I am too apt to fly out in extravagant digressions for, the thing I went to speak of, was bread only, and the several kinds of it.”17 Even when Ligon’s desire for delicacies he would have enjoyed in London distracted him from his “order,” he always returned to the organization of the natural history.

Ligon extended this rhetorical ordering to justify the treatment of animals and humans and to establish the relations among and differences between humans. He commented that when planters used “good ordering” to care for their hogs, by creating a “Park rather than a Sty” for them, the animals grew “so large and fat, as they wanted very little of their largeness when they were wild. They are the sweetest flesh of that kind, that ever I tasted.”18 Planters’ ability to order the conditions in which hogs lived allowed the animals to achieve ideal conditions of size and taste, that is, to fulfill the purpose for which the planter had purchased them. Ligon likewise employed the ideal of ordered diets to describe the differences among the human inhabitants of Barbados. He wrote, “The Island is divided into three sorts of men, viz. Masters, Servants, and Slaves.”19 These divisions were defined in dietary terms: masters ate bone meat no more than twice a week, otherwise consuming potatoes, loblolly (a porridge made from maize), and bonavist (a bean); servants ate no bone meat at all unless an ox died; and “till they had planted a good store of Plantations, the Negroes were fed with this kind of food [potatoes, loblolly, bonavist]; but most of it Bonavist, and Loblolly, with some ears of Maize toasted.”20 Prescribing diets for each group served not only as efficient plantation management but also as a method of dividing people into different categories.

Ligon extended this culinary ordering to describe Africans at work collecting and preparing plantains to eat. He created a tableau in which the actions and colors of the people in relation to the plantains produced an ordered, and thus pleasing, scene. He wrote, “But ’tis a lovely sight to see a hundred handsome Negroes, men and women, with every one a grass-green bunch of these fruits on their heads, every bunch twice as big as their heads, all coming in a train one after another, the black and green so well becoming one another.”21 Africans are described in terms of their parts, or as a single unit, or “train,” that is presented for view alongside the plantains. In Ligon’s description, the black and green colors complement one another, the size of the plantain bunches neatly doubles the size of Africans’ heads, and the slaves form an orderly, single-file train. As Ligon applied his principle of order to people and objects alike, he established connections between plantations and parts of Africans’ bodies based upon relations of proportion and color. The same rhetorical and literary strategies that ordered people and their food into tableaux also supported material forms of order, which placed people into groups of laborers and prescribed different diets for different groups. Good ordering is established at every level of the plantation system, and it thus undergirds not only how natural historians such as Ligon attempted to describe phenomena in the West Indies but also how people from planters to slaves sustained themselves.

These rhetorical and material forms of “good order” were especially crucial in the case of cassava, a staple of enslaved Africans’ foodways. Ligon carefully arranged his discussion of the various elements of the “small tree or shrub, which they call Cassava,” for he placed the edible root in the category of “Meat and Drink for supportation of life,” while placing the “manner of his growth” later in the text, in a section on “Trees and Plants in general.”22 This ordering of the tree’s parts and uses was mirrored in the practices with which cassava was processed and consumed, for, as Ligon noted, order was crucial to making the root edible. He explained, “This root, before it come to be eaten, suffers a strange conversion; for, being an absolute poison when ’tis gathered, by good ordering, comes to be wholesome and nourishing.”23 The poisonous root had to be transformed into flour and, eventually, into bread through a “strange conversion” that involved “good ordering,” as enacted by a process of washing, cleaning, grating, and drying the root. Ligon explained that the planters “trust” the “Indians” to make the flour “because they are best acquainted with it.”24 Indeed, as I explain in the section below, many Europeans believed that cassava was best conve...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Series Editor’s Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I: Archives

- Part II: Representations

- Part III: Politics

- Afterword

- Notes

- Contributors

- Index