![]()

Secondary Doors in Entranceways at Pompeii: Reconsidering Access and the ‘View from the Street’

Evan Proudfoot

Introduction

It is commonly accepted (see below) that the typical Pompeian atrium house had only one set of doors to close its main entrance between the street and the atrium, and that consequently, when these doors stood open, passers-by were afforded a framed, axial view from the street into the house. But the evidence presented in this paper shows that an additional set of entrance doors was in fact common, often placed at the boundary between the entrance passage and the atrium. Combined with the other entranceway types already well known from the site, this finding calls into question the conventional labels used to identify entranceway spaces, and requires us to formulate a more nuanced, practical understanding of access, visibility, and expectations of public and private in the atrium house.

Background

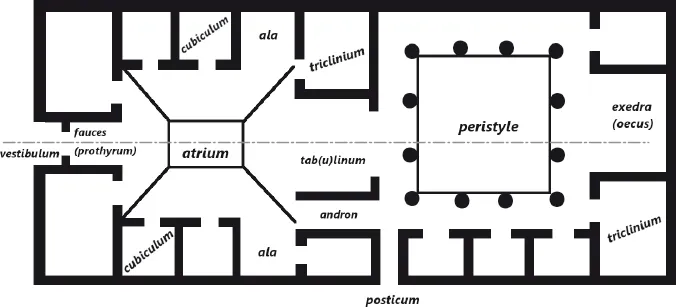

Many of the houses at Pompeii can be described as ‘atrium houses’ – buildings with a group of rooms organized around and opening onto a central, covered ‘front hall’(Allison 2004: 65–70). Asecond group of rooms is often located at the rear of the house, organized around an unroofed garden or peristyle. Modern scholars have assigned conventional Latin and Greek labels to these rooms based upon their internal proportions, syntactic relationships to other rooms, and whether they were open- or close-fronted (i.e. whether they had wide or narrow doorways) (Fig. 1). However, it is seldom possible to determine whether these modern labels correspond to ancient usage, in part because some of the labels (e.g. ‘triclinium’) conflate architectural forms with presumed furnishings or activities. Moreover, to judge from extant literary and epigraphic sources, the words used to describe these spaces had a similar polysemy even in antiquity (Aulus Gellius, Noctes Atticae, XVI.5.1; Leach 1997; Riggsby 1997).

Another notable feature of the atrium house is its axiality. The atrium is accessed from the street through a narrow entrance passage, conventionally labelled ‘fauces’, or ‘prothyrum’. This passage aligns with the tab(u)linum, a wide-fronted room at the rear of the atrium which, in the A.D. 79 configuration of many houses, gives access through a further, wide-fronted aperture at its rear to a garden/peristyle complex. In some houses, the rear of the tablinum is instead a low wall, with a large window to provide a view into the peristyle. Modern scholars have repeatedly emphasized the potential visual axis created by this alignment of fauces–atrium–tablinum–peristyle (Le Corbusier [1923] 1958: 140–160; Drerup 1959; Bek 1980: 164–203; Jung 1984; Wallace-Hadrill 1988: 82, 88–89, et passim; Wallace-Hadrill 1994: 44, et passim; Clarke 1991: 2–6, 87, et passim; Hales 2003: 102–122; Nevett 2010: 65, et passim; Sewell 2010: 161–163). Even so, the removal of the rear tablinum wall was a relatively late phenomenon, and in practice most tablina could be closed at the rear by folding doors, or separated from the atrium by curtains, or movable or structural partitions. By comparison, the narrow ‘fauces’ entrance passage has historically been regarded as a space entirely open to the atrium, unfurnished with doors or partitions except for the main, front doors of the house which closed the doorway from the street (cf. ibid.; Ivanoff 1859: 82; Overbeck and Mau 1884: 255; Greenough 1890: 8–12; Smith et al. 1890: 669 s. v. ‘domus’; Lauritsen 2011: 69). In this view, when the front doors stood open, passersby were purportedly afforded a framed, axial view from the street or entrance passage into the atrium and beyond (Fig. 2). More elaborate syntheses have taken this ‘visual transparency’ as a ‘vivid sign of [the] lack of privacy […] of the Roman house’ (Wallace-Hadrill 1994: 44; cf. Gell 1832: 152–153). Yet while perceptively distinguishing between planned ideals, built structure, and everyday practice, these characterizations fail to express the degree of structural control provided by architectural fixtures and furnishings. Instead, we read of visually arresting mosaics placed at the boundary between entrance passage and atrium (Hales 2003: 109–111), and of access controlled (perhaps figuratively) by visual surveillance and slaves who ‘functioned like doors and partitions’ (Clarke 1991: 6, 13; cf. Wallace-Hadrill 1988: 78). Such nuanced readings of domestic space are insightful, to be sure: the decoration and framed, axial alignment of the atrium house are unmistakably deliberate design features. But the evidence for closures has been downplayed to fit a preferred narrative of the public aspect of the Roman house, and this has inadvertently led to the mischaracterization of a diachronically and socially more complex situation.

Figure 1: Plan of an idealized atrium house, showing modern conventional labels for the main rooms and the axial alignment of fauces–atrium–tablinum–peristyle (dashed line). (Illustration by the author, after Mau 1899: 241 Fig. 110)

The allegedly single set of entrance doors has long led scholars to see Pompeian entranceways as analogs for those described by Roman authors. This is particularly true in comparison to Vitruvius’ (De Architectura, VI.7.1) description of the Greek entranceway, which has been interpreted as an inherently contrastive statement with respect to putatively ‘Roman’ entrances:

Figure 2: An axial view through the Casa delle Nozze d’Argento (V.2.i) from the main entrance. In its A.D. 79 configuration, the entrance passage was closed by doors at both ends. The front jambs of the tablinum had possible curtain or partition fittings (a pair of figured bronze discs with protruding ship bows (Sogliano 1892: 274; Sogliano 1896: 424; Mau 1893: 33), and the rear of the tablinum was closed by a solid-panel, quadri-valve door (Mau 1893: 33). (Photo by the author)

‘The Greeks, because they do not use atria, do not build them; but going in from the ianua [ab ianua introeuntibus], they make passages of not-so-spacious width [itinera faciunt, latitudinibus non spatiosis]. And from one part (they make) (?)stables [[e]qu[i]lia], and from the other part (they make) chambers for the doorkeeper [ost[i]ariis cellas]. And these passages end immediately with interior ianuae [statimque ianuae interiores (?)finiuntur]. This place between the two sets of ianuae is called (?)θυρω{ρώ}ν in Greek [hic autem locus inter duas ianuas graece (?) θυρω{ρώ}ν appellatur], and thereafter is the entrance into the peristyle.’ (my translation; Latin text adapted from Choisy 1909; Ruffel 1964; Callebat 2004)

But there are several problems with this assumption, not least of which is that nowhere in the De Architectura does Vitruvius explicitly describe the layout of a ‘Roman’ entranceway. In a passing comment (VI.7.5), he nevertheless mentions that ‘in Greek, the vestibula before the ianuae are called πρóθυρα [lit. ‘the (space) before the doors’]; we however call prothyra what in Greek are called διáθυρα [lit. ‘the (space) between the doors’]’ (my translation). Problematically, this is the only recorded use of the word διáθυρα in all of Greek and Latin literature (Callebat and Fleury 1995: 355). Still, early scholars such as Desiré Raoul-Rochette (1828: 11–13) preferred to draw parallels between Pompeian entrance passages and Vitruvius’ Greek variety. François Mazois (1822: 49, 52–53, 288–289) even imagined the entrance to his fanciful Palais du Scaurus with two sets of doors, and in the book’s second edition he defended this reconstruction by appealing to houses at Pompeii:

‘Quelques personnes, dont je respecte le savoir, ont paru douter de l’existence du prothyrum dans les habitations romaines. J’ai en conséquence fait graver la vue d’un prothyrum de Pompéi. [...] a fin d’exprimer clairement l’existence des deux portes aux deux extrémités du prothyrum.’ (Mazois 1822: 288–289, plate III)

Critically however, Mazois neglected to explain the evidence upon which this interpretation was based – even when the claim was reprinted two years later in Les Ruines de Pompei (1824, Vol. 2: 18–19, et passim). Soon afterwards, the English scholar William Gell (1832: 146) also recognized traces of an inner entrance door, this time in the Casa del Poeta Tragico (VI.8.3−5), but again, he failed to specify his evidence.

Not everyone agreed with the two door theory: in 1859, Sergio Ivanoff published an influential study entitled Varie Specie di Soglie in Pompei ed Indagine sul Vero Sito della Fauce, which included some of the first illustrations of plaster door casts, a preservation technique recently developed (Pagano 1994: 189). Although a noteworthy publication in this respect, Ivanoff tacitly assumed that all architectural doors required stone thresholds, and this led him to reject the earlier claims of Mazois and Gell:

‘[I] moderni autori i quali pongono in mezzo altre porte oltre [delle ianuae principali], sia tra le ante della strada, sia tra le ante dell’atrio, cadono manifestamente in errore.’ (Ivanoff 1859: 82)

This assertion was taken up by J. B. Greenough (1890) in what was to become an even more influential study of the Roman fauces. Recapitulating Ivanoff’s arguments, Greenough asserted that the term ‘fauces’ must refer to the entrance passage at the front of the house, rather than the side passage parallel to the tablinum as earlier scholars had argued (Mazois 1822: 87; Gell 1832: 159; Gusman 1899: 307). His identification found support in a seemingly backward definition of the word given by Aulus Gellius (Noctes Atticae, XVI.5.12) and repeated by Macrobius (Saturnalia, VI.8.22). But it hinged upon an alternative interpretation of De Architectura, VI.3.6, where Vitruvius prescribed that a feature called ‘fauces’ should take its width in proportion to that of the tablinum. Greenough’s (1890: 8) reading relied especially upon the notion that the entrance passage was open to the atrium, and from this point on, the term ‘fauces’ gradually became the standard term for entrance passages in the atrium house. Meanwhile, the myth that secondary doors in entranceways were rare or non-existent persisted, despite the many traces that came to light as major excavations continued over the next seventy-one years.

Defin...