![]()

CHAPTER 1

Getting Organized

In the early 1920s, Arkansas had one foot in the rustic ways of the nineteenth century and another foot in the modern era. In the Ozark and Ouachita Mountains of the northern and western parts of the state, farmers scratched together a living on small plots of land and lived in a manner much like their grandparents in the Civil War era. In the rich agricultural land of eastern Arkansas, Black and white sharecroppers navigated a relationship with plantation owners that had also changed little in fifty years. Rural Arkansas was a land of small cabins, kerosene lamps, dirt roads, general stores, and Baptist churches. Visible in the market towns and county seats, and especially in the capital and biggest city, Little Rock, were the signs of twentieth-century progress. Automobiles traversed paved roads. Telephones and electricity were taken for granted. Men joined the Masons, the Elks, the Odd Fellows, and the Knights of Pythias. Women had their clubs and tea parties. Larger congregations of Methodists, Presbyterians, and Disciples of Christ were options to join in addition to Baptist churches. There might even be a Roman Catholic parish and, in a few towns, a Jewish synagogue. The Klan would appeal to townsmen and women more than rustic country folk, and it used the technology of modern times. Yet, in many ways, Klansmen and women seemed afraid of change and romanticized a past that seemed to be crumbling away.

Although this Ku Klux Klan did not arrive in Arkansas until 1921, it had been founded on Thanksgiving night, six years earlier on Stone Mountain, near Atlanta, Georgia, when William Simmons and a group of friends raised a burning cross in a ceremony, inaugurating the Invisible Empire of the Ku Klux Klan. Simmons had an undistinguished past as a self-proclaimed Methodist preacher, an organizer for fraternal organizations, and an occasional salesman of various items ranging from garters to insurance. He sketched a set of rites and offices, reserving the top position of Imperial Wizard for himself. The costumes, rituals, and symbolism clearly hearkened back to the Reconstruction-era Ku Klux Klan, founded by former Confederates in Tennessee in 1866. The original organization’s purpose had been political: to keep freedmen from voting after they received the right with the Fifteenth Amendment. Usually called the “Ku Klux,” the masked order had been well organized in Arkansas. But the Reconstruction Republican governor, Powell Clayton, declared martial law in much of the state and stopped the Ku Klux in its tracks. Historians have credited Clayton as singularly successful in thwarting the KKK, more so than in any other southern state, because of his willingness to use military force.1

But Simmons’s Klan of 1915 was not purely a throwback to the original Klan. It gained inspiration from D. W. Griffith’s film about the Reconstruction Klan, The Birth of a Nation, which had premiered earlier in the year. The film was based on Thomas Dixon’s novel, The Clansman, which had added some whimsical touches not used by the original Klan, such as the burning of a cross. One of the first ever blockbuster movies, The Birth of a Nation thrilled audiences with scenes of freedmen on a rampage, in alliance with white carpetbaggers, until the Ku Klux Klan rode in to defend the honor of white women and restore order. President Woodrow Wilson enjoyed a private screening of this silent film in the White House. As The Birth of a Nation ran in theaters, Simmons began recruiting into his Klan “One Hundred Percent Americans”—white, Protestant, native-born men, aged eighteen and older.

Simmons had little success over the next few years. By 1920 this revived Ku Klux Klan could claim no more than a few thousand members in the states of Georgia and Alabama. Things changed dramatically that year when the founder hired two professional marketing agents, Elizabeth Tyler and Edward Young Clarke, who used a recruitment strategy reminiscent of a pyramid scheme. Professional recruiters, called Grand Goblins, worked as regional representatives who developed a network of state recruiters under them, called King Kleagles, who each had a local group of Kleagles working beneath them. Of the ten-dollar fee a new Klansman would pay at initiation, four dollars stayed in the pocket of the local Kleagle, while one dollar went to the King Kleagle, fifty cents to the Grand Goblin, two dollars fifty cents to Tyler and Clarke, and the remaining two dollars to the Klan central treasury in Atlanta. Kleagles began recruiting within lodges of existing fraternal orders, such as the Masons, the Elks, and the Odd Fellows. They also targeted men’s groups in local Protestant churches and gave free memberships to ministers. Membership skyrocketed in southern and midwestern states in 1920 and early 1921. Founder Simmons, along with promotional geniuses Clarke and Tyler, became wealthy almost instantly.2

By 1921 the Klan was well established in Texas, Oklahoma, and Louisiana, but it had no presence in Arkansas. In February William Simmons announced he had received numerous requests from prominent citizens throughout Arkansas who wished to organize the Ku Klux Klan there. He sent representatives to Arkansas to confer with interested individuals and pledged to establish the Klan in every city and town in the state.3 By the summer, Allen E. Brown and his older brother, Lloyd J. Brown, arrived from Houston, Texas, to organize the Klan in Arkansas. Allen Brown had the title of King Kleagle, and the two men worked out of a room in the Marion Hotel in Little Rock. They organized Arkansas’s first chapters in Little Rock, Fort Smith, Pine Bluff, and Texarkana, where apparently a chapter already existed on the Texas side of the border. More than five hundred men, mostly business and professional people, were reported to have joined in the first week of August. In the fall, recruiters traveled the railroads and organized Klans in towns between Texarkana and Little Rock—Prescott, Gurdon, Hope, Hot Springs, Arkadelphia, and Malvern—and between Little Rock and Fort Smith, including Conway, Morrilton, Russellville, Clarksville, and Ozark. By the beginning of 1922, it appears that more than thirty Klans in the state had applied for charters.4

The Little Rock chapter received its charter from Klan headquarters on October 3, 1921, becoming Klan No. 1 in what would be designated the “Realm” of Arkansas. Around the same time, a charismatic Missionary Baptist preacher in Little Rock, Reverend Ben M. Bogard, held a tent revival in which he thanked God for the KKK and One Hundred Percent Americanism. The Roman Catholic diocesan newspaper labeled one of his revival meetings as camouflage for a Klan gathering of five hundred persons. Later that month Bogard announced he had joined the Klan, and he preached a special sermon, lauding the order to one thousand people at his church at 21st and Brown Streets. He invited local Klansmen to attend in their regalia. By Christmas, the Little Rock Klan No. 1 claimed 2,500 members.5

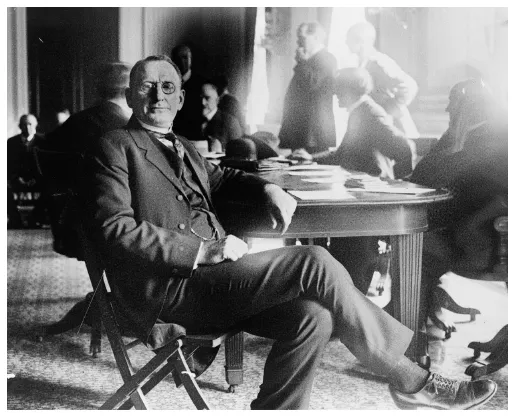

While the recruiters were busy in Arkansas, the Klan received some free publicity in Washington, DC. In October the US House of Representatives, spurred by hostile news coverage of the Klan in mostly northern newspapers, especially the New York World, began an investigation of the secret society. Though it lasted only a few days, it gave Imperial Wizard Simmons a soapbox to expound about the respectable nature of the order. Simmons denied accusations that the Klan was a terrorist organization, that it used violence, and that it was in fact anti-anything. Congress took no action, but newspapers throughout the country reported the details of the investigations and speeches. Overnight, the Klan became a household name.6

From its beginning in Arkansas, the Klan’s dominant personality was James A. Comer, a Little Rock attorney. He was the Exalted Cyclops of the Little Rock Klan until May 1924 and would serve as the only Grand Dragon for the Realm of Arkansas after it was officially established in January 1922. Comer eventually became the most public face of this secret society in Arkansas and one of the inner circle of Klan leaders nationally. Yet he was a rather enigmatic figure, in some ways unprepared to lead a white supremacist organization.

William Simmons at the congressional hearing, October 1921. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Born in East St. Louis, Illinois, in 1867, Comer attended what would become Valparaiso University in Indiana. In the early 1900s Valparaiso claimed to be the second largest private university in the United States. It fell on hard times in the later 1910s, and in the summer of 1923 the Klan made a bid to buy the university. The attempt at a “Ku Klux Kollege” failed however, and two years later the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod purchased Valparaiso. Shortly after college, Comer married Elma Coble of Delphi, Indiana, and the couple moved to Little Rock, where he managed a branch of the Union Pacific Tea Company. In quick succession the Comers had two sons, James Omer and Eben Darwin. The family lived at 606 Rock Street in downtown Little Rock. In addition to his work and parental duties, the young father began to study law. Admitted to the Arkansas bar in 1897, Comer opened his own law office, but he kept his finger in several business pursuits. He bought and resold tax-delinquent properties, and for a while he partnered with his younger brother, Omer Julius Comer, who had followed James to Arkansas, in an installment goods store at 702 Main Street.7

James and Elma Comer were active in church and social organizations. The couple attended First Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) in downtown Little Rock, where James taught for many years a men’s Bible class. He occasionally filled the pulpit when the pastor was away. James was a member of several Masonic groups, while Elma was active in the Order of the Eastern Star and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). James’s Bible class sent him to a national conference on Prohibition in Atlantic City, New Jersey, in 1915, the year that the Arkansas general assembly passed a law to make the entire state dry. By all accounts, the couple was well integrated into the respectable middle-class community of the capital city.8

James Comer became active in the local Republican Party and eventually Theodore Roosevelt’s offshoot, the Bull Moose Party. By 1900 the Republican state committee appointed him for a speaking tour for the party through northeastern Arkansas. The party nominated him in 1906 for an unsuccessful run against a popular incumbent Democrat for the office of prosecuting attorney of the Sixth Judicial Circuit (in Pulaski and Perry Counties).9 In Arkansas, Republicans had been the minority party since the end of Reconstruction, and well into the twentieth century the party was still under the control of former governor and senator Powell Clayton. By the 1910s Republicans divided between Clayton’s party establishment, which favored keeping a role in the party for Black men, and a faction that wanted to restrict the party to whites only, in an effort to appeal to racist voters who typically voted Democratic. The Republicans who wanted the party to be open to Black and white voters took the name “Black and Tans,” while those wishing to purge African Americans from the party were known as the “Lily Whites.” This division was compounded in 1912 when Theodore Roosevelt’s bid for the Republican nomination for the presidency against incumbent President William Howard Taft split the party nationally and in Arkansas. Both the regular and Roosevelt groups were divided between Black and Tan and Lily White factions.10

On March 26, 1912, James Comer was elected, with many African Americans present, as chairman of the state Roosevelt League. In April he traveled to Washington, DC, for a meeting of state Roosevelt Leagues. He even secured a visit by Roosevelt himself to Arkansas a few weeks later. On April 20, Comer, along with several leading Republicans, including former federal judge John McClure, traveled to Fort Smith to ride the train with Roosevelt to Little Rock, where the former president spoke that evening at the Argenta skating rink. The following morning Roosevelt departed on a special train, with Comer in tow to introduce Roosevelt for speeches delivered from the rear of the car at stops in Conway, Morrilton, Russellville, Clarksville, Ozark, and Van Buren. The plans included marching bands to process to the depots with some men carrying big sticks, symbols of the former president’s approach to foreign policy. In Conway alone a crowd of two thousand heard Roosevelt speak.11

Soon after Roosevelt left the state, Comer had a real fight on his hands. At a meeting on April 25 to select Pulaski County’s delegates for the Republican state convention, the pro-Taft delegates arrived early to take their seats in the hall. Finding themselves literally shut out of the meeting, the Roosevelt men charged the door, swinging their walking sticks. A brawl resulted that did not stop until Little Rock policemen and the sheriff’s deputies arrived to restore order. Several Republicans were bleeding from wounds to the scalp, injured by flying canes. Thus ejected, Comer’s men held their own convention outside the building. Standing on a soapbox, Comer presided over the impromptu convention as it selected its own delegates.12

Under Comer’s direction the pro-Roosevelt group adopted the Black and Tan position, and even chose a Black man, Reverend Samuel A. Moseley of Pine Bluff, as one of the delegates to the upcoming Republican National Convention in Chicago. Comer and the other delegates went to Chicago in June to present their case. They particularly complained that Powell Clayton controlled the party in Arkansas, including federal appointments, even though Clayton had not lived in the state within the previous sixteen years. The Republican Credentials Committee had the onerous task of deciding who would get seated from Arkansas and other states where the party had similarly split between Taft and Roosevelt. With Powell Clayton a member of the Republican National Committee, it is no surprise that the Taft delegates were seated from Arkansas and elsewhere. Roosevelt and his supporters walked out of the Chicago Coliseum, reassembled in Orchestra Hall, and began plans for a new party. A couple of weeks later, on July 7, Roosevelt announced a nominating convention for his Progressive Party to be held August 5 in the same hall in Chicago where his supporters were denied seats earlier in the summer.13

After the Chicago debacle, James Comer immediately launched the organization of the Progressive Party, or as it was more commonly known, the Bull Moose Party, in Arkansas. About a third of those who attended the Pulaski County Bull Moose state convention in late July were African American. When Comer and other leaders proposed that four Black men serve as part of the county’s delegation of eleven to the state convention, Lily White opponents walked out, held their own meeting, and elected an all-white delegation. At the state convention that followed, Comer was elected chair of the state party. His Black and Tan position prevailed, and Black delegates were chosen along with Comer. When the Roosevelt supporters convened in Chicago’s Coliseum on August 5, they were decidedly younger and more Catholic, Jewish, Black, and female than the “Regular Republicans” who had met in the same hall just six weeks before. The platform they adopted championed progressive positions, such as conservation, women’s suffrage, limits to campaign spending, the right of labor to organize, the eight-hour day and six-day work week, workplace safety, and Social Security–type measures to protect against unemployment, old age, and disability. Comer hosted Teddy Roosevelt again in September when the candidate made a campaign swing through the state. The future Klan leader campaigned tirelessly, including speaking on behalf of Roosevelt at meetings of the Negro Roosevelt Progressive League in Black churches.14

Roosevelt speaks to an adoring crowd at Fort Smith in 1912. Courtesy Pebley Center of the Boreham Library, University of Arkansas Fort Smith, Chamber of Commerce Collection.

In November, Roosevelt won more votes than the Republican incumbent Taft, but of course both lost to the Democratic candidate, Woodrow Wilson. But the Bull Moose Party did not immediately die. James Comer remained its leader in Arkansas into 1916 when the party merged back into the GOP. At the last convention of the Arkansas Bull Moose Party in March 1916, delegates declared they would recognize no color line even if it might stall their union with the state Republican Party, which still had its Lily White faction.15

After the collapse of the Progressive Party in 1916, Comer had a lower public profile. When the United States entered World War I in 1917, he gave frequent speeches promoting the war effort in theaters, public schools, and the YMCA, seeming to specialize in pushing Liberty Loans to Black audiences in churches and at the Mosaic Temple at 9th and Broadway and other venues. In 1918 he was a pallbearer at the funeral of Charles M. Simon, a prominent Little Rock Jew. As late as 1920, he still pushed the Black and Tan position in the Arkansas Republican Party against the majority under leader Augustus Caleb Remmel and other Lily Whites.16 Comer’s activities seem unconventional for someone who the next year would emerge as leader of a group...