![]()

1

FAYETTEVILLE

DAVID BUEGE AND JEFF SHANNON

Poet Miller Williams has described Fayetteville, Arkansas, as a “tree-thick mountain town”1 for its modest forested topography in the Boston Mountains, at the edge of the Ozark Plateau. The University of Arkansas and iconic Old Main occupy one nominal mountain, and the revitalized town square, once the vibrant commercial and civic center before the malls came, occupies another. Townscape and bucolic academy are juxtaposed on these topographic twins, with Fayetteville’s cultural and entertainment districts adjoining between and below. Fayetteville has been the cultural capital of northwest Arkansas but now has competition from nearby Bentonville with the recent completion of Alice Walton’s Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, designed by architect Moshe Safdie, and the 21c Museum Hotel by Deborah Berke.

Home to a number of internationally prominent persons, Fayetteville is the birthplace of Edward Durrell Stone and his childhood friend, former US senator J. William Fulbright. Fulbright served as the president of the University of Arkansas for a short period, and was progenitor of the Fulbright Program, the prestigious international exchange program for scholars. As a senator, he was chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and an early critic of the war in Vietnam. Stone was the architect for the first permanent quarters for New York’s Museum of Modern Art in the late 1930s (with Philip Goodwin) and for some little known but rather extraordinary modernist houses. Fulbright’s friendship was probably beneficial for Stone when he received the commissions for the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, DC, and the United States Embassy in New Delhi. Stone was also the architect for the University of Arkansas’s estimable Fine Arts Center, built in 1952 for programs in the visual and performing arts, and home for the earliest years of the Department of Architecture. In one of his numerous visits in support of the new architecture program, Stone reputedly, and perhaps aptly, described 1950s Fayetteville of as “a hot-bed of tranquility.”2

Fay Jones came to prominence as the most accomplished architect in the group representing the earliest students and first teachers in the nascent Department of Architecture at the University of Arkansas. Initially a program within the College of Engineering, the department was founded by John Williams, somewhat accidentally, little more than a decade after the completion of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater and contemporary with Wright’s Usonian houses. Many in the department drew inspiration from the example of Wright, applying this inspiration mostly in the design of modest residential projects at a time when most Americans favored, and the Federal Housing Administration encouraged, vast tracts of virulent, mass-produced houses. Because the ubiquitous post-war American taste in domestic architecture prevailed in this diverse Ozarks community, a sense of adventure and an appreciation for “contemporary” or “progressive” or “modern” architecture were prerequisites for prospective clients. University professors were amongst the few in the limited pool of those who were open to modern architecture. The architecture of the sort we now identify as mid-century modern was informed by Wright’s exemplars, the more modest Usonian houses especially. For the most noteworthy architects who practiced in the Ozarks and at the edge of the prairie, real and mythical, Usonia represented the spirit of the age, and wood was the material of choice. There are early examples of Jones’s own modest wood variants on Wright’s Usonian houses. In Fayetteville, this includes the Barnhart House and the Burdick House, both from 1950. From the beginning, Jones worked without contracts, as trusting as he was trustworthy. He was confident that the clients, contractors, and tradespeople with whom he worked were as ethical and capable as he.

Wright was a collector of Japanese prints and found inspiration in the art, architecture, and culture of Japan; he traveled there often. From furniture maker George Nakashima who designed a chair for Knoll and who was featured prominently in the pages of LIFE magazine to Peter Eisenman teaching traditional Japanese detailing to Anthony Vidler at Cambridge University,3 strong intimations of japonisme were present in architecture and design during this period.

Mount Kessler, Mount Nord, Mount Washington, and Mount Sequoyah are amongst Fayetteville’s most prominent natural features. At night when a large, illuminated cross stands poised near its crest, Mount Sequoyah is especially prominent. For many it is the landmark most characteristic of the town, the university’s Razorback football stadium aside. Originally known as East Mountain, it was from this promontory that Confederate forces shelled the town below in 1863. Now largely residential, Mount Sequoyah is where Jones built many houses: modest, monumental, and everything in between, including Jones’s Goetsch-Winckler House. This was the second Goetsch-Winckler House. The first, by Frank Lloyd Wright, was designed and built years before in Okemos, Michigan.

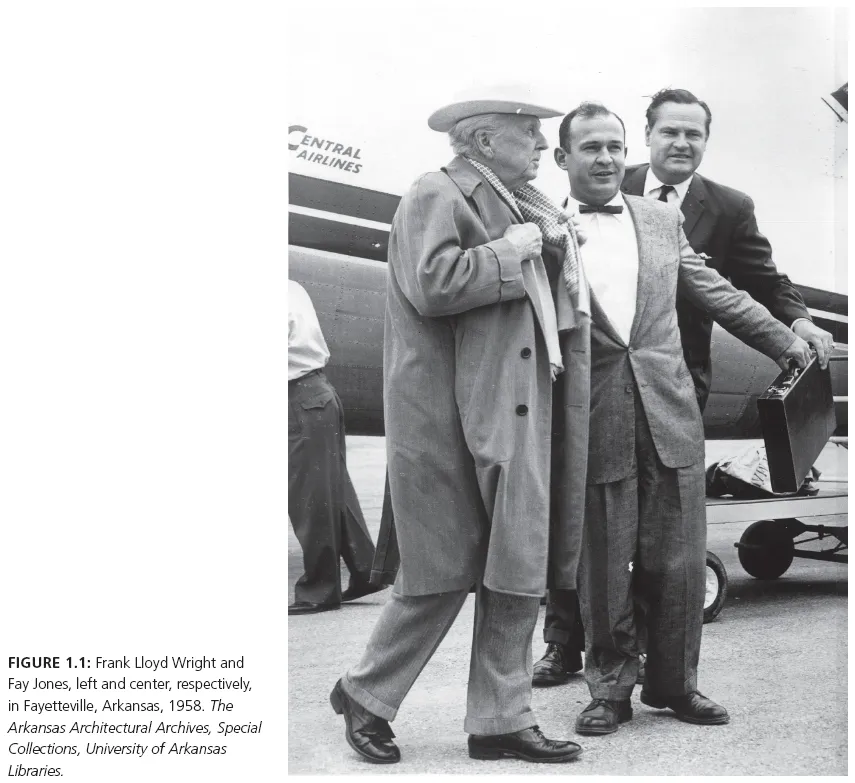

Wright visited Fayetteville in 1958 to spend time with Jones and to give a lecture at the university (Figure 1.1). In a conversation with Jones while visiting Jones’s Fayetteville house, and illustrated by a priestly gesture, Wright differentiated the essence of his sensibility from that of Jones. Moving his hand horizontally, Wright referred to what he saw as an essential characteristic of his architecture as inspired by the horizontality of the prairie. Then, moving his hand up and down, he illustrated what he saw as the equivalent difference for Jones. Perhaps it was a simple reference to the vertical battens on Jones’s house.4 Or, it may have been Wright’s summary understanding of the essential character of this place in which Jones worked and lived, this “tree-thick mountain town” where verticality was suited to the hills and trees of Fayetteville. He may have wished to describe a distinction between his own earthly architecture and something spiritual or sacred that he saw in Jones’s architecture, or it might simply have been a gentle admonishment, that by understanding this and taking it to heart, Jones might allow some greater distance between himself and Wright. However one might understand this exchange, Jones made it clear in comments to his staff that he understood Wright to be making the point that Jones should find his own way.5 Architecture aside, there were, of course, striking differences in personality and character. Jones’s humility was antithetical to Wright’s audacity and super-sized ego, and the personal ethos of each was quite distinct.

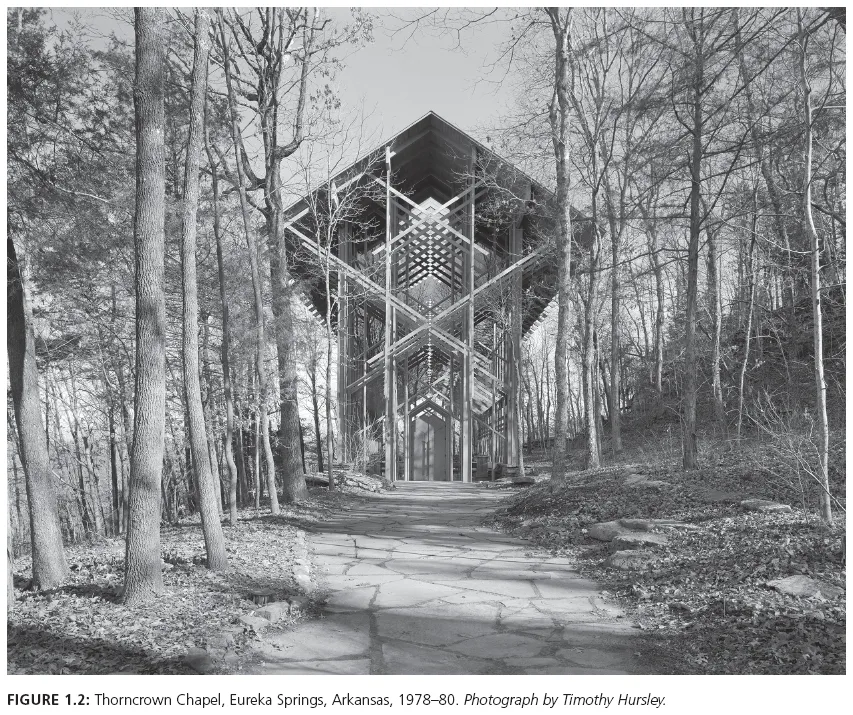

With the completion of Thorncrown Chapel in Eureka Springs, Arkansas, more than twenty years later, Jones’s response to Wright’s suggestion was most profoundly realized. As one approaches the chapel, the front elevation foretells the verticality of the interior space (Figure 1.2). Once inside, the rich detail of the web-like, interlaced structure overhead enhances one’s experience of this otherwise straightforward, vertical space. Emerging from the shadow of Wright, the success and achievement of Thorncrown and the acclaim it received were liberating for Jones. With quiet confidence he expressed the implications of Thorncrown for his future work by embracing, in principle, the formal modesty and leitmotiv of a simple rectangular volume and gable roof.6 These alone, he said, would offer sufficient opportunity for a lifetime of work. Pre-Thorncrown Stoneflower in Eden Isle, Arkansas, and post-Thorncrown Hogeye, Roy Reed’s Arkansas home, are the houses most emblematic of this, and arguably the best of the few that were realized with this formal restraint and simplicity.

Like Wright, Jones was insistent that architecture must be specific to the place and responsive to the character of a setting, and that good architecture could happen nearly anywhere. For Jones, the stronger the natural qualities of a site, the more he could invest the setting with his version of a pastoral or arcadian ideal by drawing upon those natural characteristics and the inspiration of the genius loci. The Edmondson House in Forrest City, Arkansas, and its dramatic hilly site within the loess-soil landscape of Crowley’s Ridge, are exemplary in this regard. Elsewhere and in contrast, the less arcadian a site the more it appears that Jones devised strategies to subtly distance (and conceptually detach) the architecture of a house from the realities of the setting and to instead offer allusions to his absent ideal.

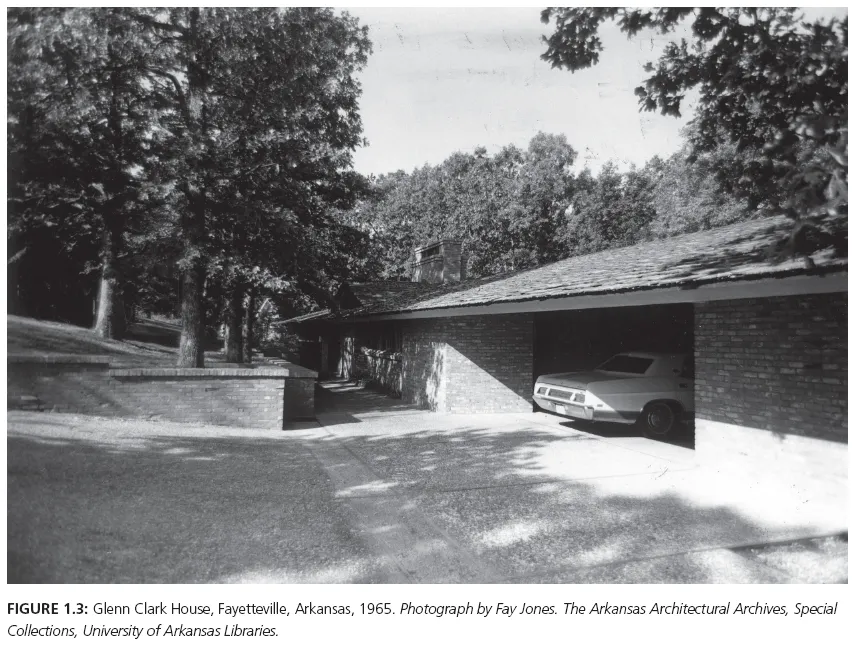

What Jones described as “my most important thoughts” were collected on handwritten five-by-seven-inch note cards stored in a shoebox. “The house in an arcadian landscape—a symbiotic arrangement,” said one, describing Jones’s ideal for a house and its setting. This ideal situation, and an arcadian site, however, was rarely presented to Jones, especially in the early days of his practice in Fayetteville. Most often the sites for which he designed were conventionally suburban, ordinary, and less than compelling—certainly not pastoral or picturesque. They had few of the qualities of the arcadian landscape he might have dreamed of. In response to this dearth of better sites, Jones developed site strategies to mitigate the deficiencies of mundane, suburban-like settings, and to diminish the presence of the prosaic, domestic architecture of existing or possible neighbors. One such strategy is seen in the Glenn Clark House of 1965.

A cut-and-fill strategy was used for the Clark House, reconfiguring the sloping terrain to provide a level base on which to build. This strategy also allowed Jones to enhance privacy for the family by a conceptual distancing of the house from the street. At the line of the cut, running parallel to the main axis of the house, Jones built a masonry retaining wall. As a result, from the street there is the perception that the house has been set low in the slope, and that the wall of the house occupies a shadowed recess between the foreground landscape and the roof (Figure 1.3). A paved walkway between the retaining wall and the house leads from the driveway to the front door, and a curvilinear walk connects directly to the street. The roof becomes the dominant element, and there is a suggestion that the house is more allied with the hill than the street. Under the deep overhang of the roof, Jones inserted his version of a ribbon window high enough in the wall to ensure some visual privacy for inhabitants but low enough to provide a view from the interior to the street. The retaining wall quite literally provides a base in the formal composition of the house and, with the foreground landscape and the dominant, projecting roof, defines the most public face of the house as a deeply shaded mask. In addition to enhanced privacy, the strategy also provides a degree of detachment from the banality of the suburban condition of the street and from close-in neighboring houses. Jones used this strategy with several other houses, notably the Harmon House of 1958 and the Hotz House of 1978, both in Fayetteville.

Providing an interesting later variant on the cut-and-fill strategy of the Clark House, the Nelms House of 1990 was designed for a conventional, upscale neighborhood within quick, easy striking distance by golf cart of the Fayetteville Country Club atop an otherwise modest plateau on Fayetteville’s south side. It is a neighborhood with very few houses with architectural pretensions, and even fewer designed by architects. Streets and the mostly flat, subdivided land are like those of any conventional suburban development that has been painted with the faux picturesqueness favored by civil engineers, bankers, and realtors, with not a hint of the sort of nature with which many associate Jones, and with which Jones wished to associate. Designed during the last third of Jones’s career and on the heels of Mildred B. Cooper Memorial Chapel in Bella Vista, Arkansas, the Nelms House is a more overtly suburban take on themes previously developed in his work, executed here in something closer to an American ranch house but at a somewhat larger scale than was typical in Fayetteville and northwest Arkansas at that time.

For the Nelms House, Jones developed a variation of the Clark House strategy for shielding the house with a retaining wall. Rather than cutting into the minimal slope, Jones raised the foreground level of the front yard, and backfilled it to a retaining wall.7 For Nelms, there was no “cut,” only “fill.” The perceptual effect from the street is similar to that of the Clark House, with the suggestion that the house was planted lower into a slope where little slope had actually existed (Figure 1.4). This simple strategy helped Jones resolve the dilemma posed by conventional sites meeting arcadian ambitions. Jones had used this inverted cut-and-fill strategy earlier at the Polk House of 1970 in McNeil, Arkansas.

With this sectional enhancement for the site, Jones provided sufficient space for a walkway between the retaining wall and the main body of the house. Nelms had asked for a front porch from which to view the street, and for socializing with neighbors who might be walking by.8 The porch was not an element that Jones often used. If the request conjured up images of cottages with front porches lining a street, as in the neo-traditional, New Urbanist neighborhoods of Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, Jones’s response was simply to widen a portion of the walkway between the retaining wall and the house to provide the requisite sheltered sitting area (Figure 1.5). The retaining wall is high enough to provide a degree of enclosure and privacy from the street but low enough to allow eye contact and conversation with passing friends and neighbors.

Privacy for the house was threatened by a number of small lots to the rear, so Nelms purchased them to ensure privacy, and to protect the setting for the house that Jones was to design. These additional lots came to be known as “Nelms’s Park.”9

In early sketches for the Nelms House, Jones rotated the house approximately twenty degrees from parallel with the street, apparently preferring to orient the house to the contour lines of the gentle topography of the site, and suggesting that Jones was interested in denying the conventional geometric interrelationship of the house, street, and adjacent houses. His staff argued against this strategy, successfully, and the house was oriented parallel to the street.10

Viewed from the street, it may not be immediately apparent that the architecture of the Nelms House is the work of Fay Jones. There are intimations of Prairie House lines and proportions in the Nelms House, in colors and materials that are almost more typical of suburban houses than those most often associated with Jones, proof perhaps that Jones’s work was not so doctrinaire, nor even especially dependent upon natural materials, the wo...