![]()

CHAPTER ONE

A Land “Inferior to None”

Happen! happened in Arkansaw: where else could it have happened, but in the creation State, the finishing-up country—a state where the sile runs down to the center of the ’arth, and the government gives you title to every inch of it? Then its airs—just breathe them, and they will make you snort like a horse. It’s a State without fault, it is.

—THOMAS BANGS THORPE, “The Big Bear of Arkansas”

The soil of the Arkansas bottoms is inferior to none in the world.

—ALBERT PIKE, letter to the New England Magazine, 1835

Millions of years before the first human being set foot there, dynamic forces were shaping the land that would become the state of Arkansas, making it one of the most varied and beautiful in the American nation. Some 500 million years ago, all of present-day Arkansas was covered by the waters of what we now know as the Gulf of Mexico. Shallow waters teeming with marine life covered the northern part of the state, and as sea creatures died their shells became incorporated in bottom sediments that later formed into limestone. The tiny fossils that can be found today in that limestone provide a record of this era in the state’s geological history. Over time, the land began to emerge from the water, as ancient continents collided to form a supercontinent called Pangea. The first to emerge was the land in the northern and western regions, where the collision of continents gradually thrust the land upward. The land in the southern and eastern parts of Arkansas remained underwater for a much longer period. When the waters finally receded from this region, they left a flat and rolling landscape that resembled the ocean floor it had been for so long. See plate 1 following page 126.

At the conclusion of this lengthy period of dynamic change (roughly one million years ago), Arkansas assumed the general geologic pattern that exists today. A diagonal line running northeast to southwest divides the state approximately in half, with the areas north and west of the line being characterized by mountainous uplands, while the southern and eastern parts are flat or rolling lowlands. This geologic division would have profound implications for social, economic, and political development in Arkansas. But for all its significance, this division of Arkansas into highlands and lowlands greatly oversimplifies the complex nature of the state’s geology. Today geologists recognize six major natural divisions in Arkansas. Three—the Ozark Mountains, the Ouachita Mountains, and the Arkansas River Valley—make up the highland region, and three others—the West Gulf Coastal Plain, the Mississippi Alluvial Plain (the Arkansas Delta), and Crowley’s Ridge—constitute the lowlands. See plate 2 following page 126.

The Ozark Mountains

Perhaps the most well known of these natural divisions is the Ozark Mountains. Occupying the northwest corner of the state, the Ozarks reach elevations over two thousand feet higher than in the lowlands. See plate 3 following page 126. Technically, these mountains are actually what geologists call an elevated plateau. After the continental collision forced this land upward, a long process of erosion began that gradually lowered the surface of the land until it reached layers that were resistant to erosion. The result was the creation of a relatively flat, level plateau. Over long periods of time, rivers dissected the Ozark Plateau creating three smaller, discontinuous plateaus separated by valleys and erosional remnants in the shapes of hills and mountains. These plateaus are called the Springfield Plateau, the Salem Plateau, and the Boston Plateau.

The Springfield Plateau extends westward from St. Louis, Missouri, to southwest Missouri, northeast Oklahoma, and northwest Arkansas. It is composed largely of highly soluble limestone and a flint-like rock called chert that was an important resource for stone tool-making American Indians during the prehistoric era. Much of this plateau is forested, but sizable areas of prairie with level land and tillable soil drew early settlers from southern Missouri to the area. Today the cities of Fayetteville and Springdale (Washington County), Rogers (Benton County), and Harrison (Boone County) are located in the Springfield Plateau.

North and east of the Springfield Plateau lies the Salem Plateau. The vast majority of this plateau lies in Missouri, but the southernmost part crosses the border into north-central Arkansas. The soil here is much thinner and poorer than in the Springfield Plateau. Some nineteenth-century accounts described large parts of the region as “barrens.” Today, Eureka Springs lies on an escarpment between the Springfield and Salem Plateaus, and the towns of Mammoth Springs (Fulton County), Mountain Home (Baxter County), Calico Rock (Izard County), Cherokee Village (Sharp and Fulton Counties), and Yellville (Marion County) are located on the Salem Plateau.

The third plateau, the Boston Plateau (commonly called the Boston Mountains), lies south of the Springfield Plateau. Reaching elevations of up to 2,600 feet above sea level, this plateau is the highest in the Ozarks. The region is characterized by magnificent mountain vistas, but its rugged nature limited transportation and agricultural development, which led to the creation of an isolated, hill-country culture that gave the Ozarks its “hillbilly” image. The Boston Plateau was traditionally the poorest section of a region that was for much of Arkansas history the poorest in the state.

Hardwood forests of oak and hickory dominate the Ozark landscape, and clear, spring-fed rivers like the King, the Spring, the Buffalo, and numerous other streams cut deep valleys through parts of the Ozarks. The best known of these Ozark rivers is the Buffalo. Originating in the Boston Plateau, the Buffalo follows a generally east-to-west course for over 150 miles through present-day Newton, Searcy, and Marion counties before entering the White River in Baxter County. The beautiful bluffs, rapids, and waterfalls created by this river, in addition to the clear water and the abundance of fish, birds, and other wildlife make the Buffalo one of the most scenic rivers in the nation.

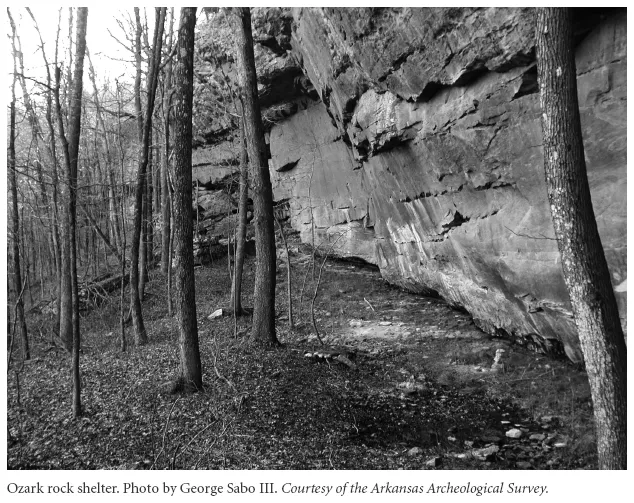

The Ozarks are also home to another of the state’s most unique features. Water seeping through cracks in the region’s limestone base causes the underlying rock to dissolve, creating large caves. The most spectacular of these may be Blanchard Springs Cavern near Mountain View. This massive underground cave contains an underground river, stalactites (formations descending from the cave’s ceiling), stalagmites (formations rising from the cavern floor), columns (where stalactites and stalagmites meet), and extensive areas of flowstone (sheet-like calcite deposits formed where water flows down a wall or along the floor). Bats, snails, spiders, and the rare Ozark blind salamander (the first cave-dwelling amphibian found in the United States) find a home in the cavern. Another geological feature—rock shelters eroded into the faces of vertical limestone and sandstone bluffs—was used extensively by prehistoric American Indians for short-term occupation. The dry environments of many rock shelters made them suitable for the storage of nuts and grains.

Travelers to the Ozarks have long been impressed by the region’s great natural beauty. The geologist Henry Rowe Schoolcraft left an account of his visit to the Missouri and Arkansas Ozarks in 1819–1820. He wrote, “It is a mixture of forest and plain, of hills and long sloping valleys, where the tall oak forms a striking contrast with the rich foliage of the evergreen cane, or the waving field of prairie-grass. It is an assemblage of beautiful groves, and level prairies, of river alluvion, and high-land precipice, diversified by the devious course of the river, and the distant promontory, forming a scene so novel, yet so harmonious, as to strike the beholder with admiration; and the effect must be greatly heightened, when viewed under the influence of a mild clear atmosphere, and an invigorating sun, such as is said to characterize the region during the spring and summer.”

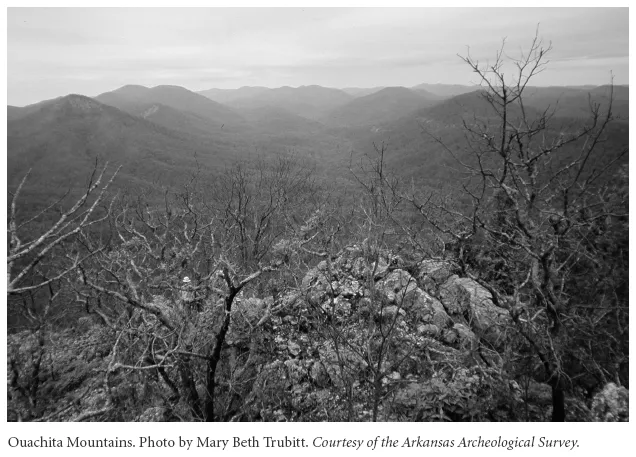

The Ouachita Mountains

The Ouachita Mountains make up the second part of the Arkansas highlands. Lying south of the Ozarks, the Ouachitas extend from eastern Oklahoma to the western edge of present-day Little Rock in central Arkansas. Like the Ozarks, the Ouachitas were created by the collision of continents, but here uplift was only a minimal factor. Rather the collision folded layers of rock over other layers. Riverine erosion accentuated the folds, shaping them into a series of east-west running ridges. Sandstone and shale compose much of the Ouachitas, but the region also has deposits of quartz crystals and novaculite, a hard, dense stone prized for use as a whetstone during historic times and by ancient American Indians as a material for stone tool-making long before that. Pine forests predominate on the warmer south-facing slopes of the Ouachita’s ridges, while the cooler north-facing ridges tend to favor hardwood forests. The valleys between the ridges are mixtures of pine and hardwood. Streams in the region tend to follow the east-west fold patterns, and rainwater that follows the folds below ground emerges at various points in the region as hot springs, most noticeably at today’s Hot Springs National Park.

On his expedition up the Ouachita River with fellow Scottish immigrant George Hunter in 1804–1805, William Dunbar described the land along the Ouachita River just below the hot springs:

From the river camp for about two miles, the lands are level and of second rate quality, the timber chiefly oak intermixed with others common to the climate and a few scattering pine-trees; further on, the lands on either hand arose into gently swelling hills, clothed chiefly with handsome pine-woods; the road passed along a valley frequently wet, by numerous rills [small brooks] and springs of excellent water which broke from the foot of the hills: as we approached the hot-springs the hills became more elevated and of steep ascent & generally rocky.

The Arkansas River Valley

In 1819 the English-born naturalist Thomas Nuttall traveled up the Arkansas River from Arkansas Post on the river’s lower reaches to Fort Smith. As he passed the point where Little Rock would soon be established, he remarked on the changing nature of the lands that bordered the great river. “After emerging as it were from so vast a tract of alluvial lands, as that through which I had now been traveling for more than three months,” he wrote, “it is almost impossible to describe the pleasure which these romantic prospects afford me. Who can be insensible to the beauty of the verdant hill and valley, to the sublimity of the clouded mountain, the fearful precipice, or the torrent of the cataract.” This region, where the river passes between the Ozarks and the Ouachitas, is known as the Arkansas River Valley. The same geologic forces that caused the Ozarks and Ouachitas to be uplifted forced the area between them downward into a trough that was carved and sculpted by the Arkansas River. Up to forty miles in width and extending from the Oklahoma border to the Mississippi River, the River Valley contains characteristics of both the Ozarks and the Ouachitas, with both uplifted plateaus and folded ridges, and pine and hardwood forests. Other features are unique to the region. The wide bottomlands provide fertile farmland and also feature bottomland forests and swamps. Pockets of coal and natural gas are also found in the region. See plate 4 following page 126.

Three unique features of the River Valley are Mount Magazine (Logan County), Mount Nebo (Yell County), and Petit Jean Mountain (Conway County). All are mesas—isolated hills with steep sides and flat tops. Mount Magazine is the highest point in Arkansas, reaching an elevation of 2,753 feet above sea level. The mountain is also famous for its diverse butterfly population. Ninety-four of the 134 species of butterflies in Arkansas can be found there, including the rare Diana fritillary. Petit Jean Mountain contains the greatest concentration of prehistoric American Indian pictographs (rock paintings) in the state. Mount Nebo was an important landmark for navigation along the Arkansas River during the early historic era. The three mountains provide magnificent views of the bottomlands and rolling uplands that characterize most of the River Valley.

Thomas Nuttall reported that he was “amused by the gentle murmurs of a rill and pellucid water, which broke from rock to rock. The acclivity, through a scanty thicket, rather than the usual sombre forest, was already adorned with violets, and occasional clusters of the parti-colored Collinsia. The groves and thickets were whitened with the blossoms of the dogwood (Cornus florida). The lugubrious vocifications of the whip-poor-will, the croaking frogs, chirping crickets, and whoops and halloos of the Indians, broke not disagreeably the silence of a calm and fine evening.”

The river itself and its adjacent lowlands have long served as a transportation corridor for both animals and people. Long before highways or railroads, the river was a major artery of commerce for early Arkansans, and some of the state’s earliest settlements grew up along its banks. Today Fort Smith, Ozark, Clarksville, Russellville, Morrilton, Conway, and several smaller communities are located in the River Valley.

The West Gulf Coastal Plain

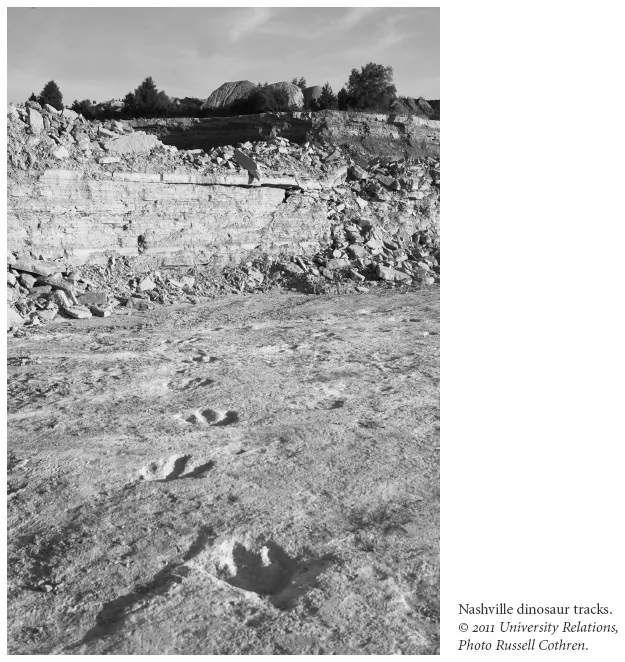

Even after most of the water that originally covered Arkansas had receded, much of the southwestern region remained covered by a wide, shallow lagoon that was home to a variety of living things ranging from microorganisms to shellfish to dinosaurs. Near present-day Nashville (Howard County), paleontologists found the tracks of a number of huge dinosaurs that had traversed the area between 150 and 200 million years ago, when the climate was hotter and much more humid than today. Recent investigations led by University of Arkansas geosciences professor Steve Boss have identified numerous species, including Acrocanthosaurus atokensis, one of the largest predators ever to roam the earth’s surface, as well as gigantic long-necked, plant-eating sauropods. The remains of the shellfish eventually formed a soft version of limestone known as chalk. See plate 5 following page 126.

Because various parts of the Coastal Plain formed at different times, the soil in this natural division varies widely. It ranges from the fertile farmland and bottomland forest of the Red River and the Blackland Prairies in the west to the later (and poorer) sandy pine-covered regions in the east. The varying soils gave rise to varying ways of life. In the western portion of the region, farming and livestock raising predominate, while in the east, timber harvesting is a major economic activity.

Several varieties of minerals are found in the Coastal Plain. Bauxite (used in making aluminum) is found in Saline County, and the discovery of oil and gas near present-day El Dorado and Smackover created a boomtown economy in the early twentieth century. A unique mineral found in the Coastal Plain comes from near present-day Murfreesboro (Pike County). Thousands of diamonds have been found at the site of an ancient volcano that exploded millions of years ago.

The Mississippi Alluvial Plain (the Delta)

The last part of Arkansas to take shape was the southeastern region. As the climate cooled dramatically some 110,000 years ago, thick glacial ice scoured northern parts of the continent. When the last vestiges of the ice sheets began to melt some 11,500 years ago, rivers filled with outwash spread deep sedimentary deposits across the more southerly regions. The Mis...