![]()

There was once a man who left his home every day to hunt deer. Each morning the man said goodbye to his pregnant wife. He also made sure that the couple’s home was secure because “many strange creatures” kept visiting their home when he was out hunting. These “strange creatures” made regular attempts to convince the pregnant woman to let them in her home so they could dance with her. Their true intentions, however, were far more sinister: these creatures “ate people [who] lived in the neighborhood.” During one of these visits, the “strange creatures” danced outside the pregnant woman’s house and coaxed her into joining them. “A short time afterwards they caught her and devoured her.”1

This tale, known in Natchez oral tradition as the “Lodge Boy and Thrown-Away,” had many forms. It was also common among other tribal polities; ethnologists recorded different versions of the tale across North America. It was a violent story, but in the version above the focus remained on the demise of the woman and the fate of her unborn twins. Once the “strange creatures” consumed the woman, they deposited one of the newborns in the “lodge” and the other was “thrown away.”2

The Natchez, who resided in the Lower Mississippi Valley, shared these types of oral traditions with family and community members. Such narratives described how people acquired game while they also prescribed what were and were not acceptable sources of flesh for human consumption. Eating human flesh was generally a forbidden way of obtaining nourishment.3 In one of the Natchez versions of “Lodge Boy and Thrown-Away,” the woman’s husband returned home after his hunt and heard only the sound of a crying baby. The man located the baby lying beside a blood-spattered leaf, the only sign of his deceased wife. The man gathered up the bloodstained leaf, fed it deer soup, and locked it in the house. He then discovered the umbilical cord that had once connected mother and child. The umbilical cord transformed into a child slightly bigger than the crying baby. Although this larger child was wild and quite strong, the man determined to capture him so that his baby might have a playmate.

After a period of time, the father “tamed” both of the boys. The brothers subsequently embarked on a number of adventures before one day encountering “a house where cannibals lived.” Curious, the boys edged closer to the house and heard the “cannibals laughing, feasting, and playing inside.” Suddenly, a number of cannibals rushed out of the house, one “carrying a baby which they set in a bowl on the fire.” The boys reacted angrily, throwing something into the bowl and cracking it. This infuriated the cannibals, who proceeded to “roast” the baby over the hot coals. Once the baby was fully cooked, the cannibals feasted and then fell asleep. Seeing the sleeping cannibals, the twins acted on their anger by tying all of the sleeping cannibals together by their hair and setting their house on fire. The house burned, and the boys fled.

These types of oral traditions attempted to illuminate socially acceptable behavior in relation to the consumption of flesh within Native communities. Oral traditions of a similar nature existed among other Native southerners, such as the Cherokees, Creeks, Choctaws, and Chickasaws and smaller polities such as the Yuchi, Apalachee, and Miccosukee. As a general rule, Indigenous people in the Southeast viewed the consumption of human flesh as taboo. But while the Natchez narratives provide us with a small historical window into Native American attitudes about cannibalism, they also inform us about the importance of oral traditions among Native peoples in the Southeast and how those traditions helped define ritual and ceremonial practices related to acceptable food sources for human consumption.

This chapter explores the connections between cannibalism, consumption, and oral tradition among southeastern Native Americans from the late seventeenth to the early nineteenth centuries. Focusing especially on the articulation of Indigenous food consumption amid colonial encounters involving Native Americans and Europeans, my analysis reveals how Indigenous oral traditions about food items and consumption were defined by both the syncretism of the different food cultures of the ever-changing settler colonial context during this period and by a spiritual and epistemological understanding of the interconnectedness of all animate and inanimate beings.

Savages, Cannibals, and the European Imagination

If Native American oral traditions such as “Lodge Boy and Thrown-Away” highlight prohibitions on the eating of human flesh, where, then, did the pervasive belief that Native Americans routinely engaged in cannibalistic activities come from? Answers to this question are not hard to find in the writings of early modern Europeans. For example, the sixteenth-century Italian explorer Christopher Columbus linked the Carib Indians of the Lesser Antilles to cannibalism.4 Over the ensuing decades, European authors routinely referred to the “men-eaters in the West-Indyes” and the “homely” diet of Native people on the mainland Americas.5 The association of Indigenous people with the practice of eating human flesh had a clear purpose: to highlight what European writers imagined was the vast gulf between Christian Europeans and the “savage” peoples of the Caribbean and Americas.

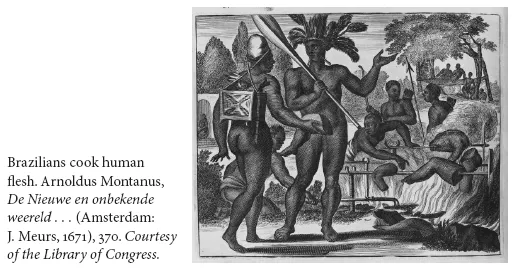

Tales of flesh-eating Native peoples in the Caribbean, the mainland Americas, and ultimately throughout the Pacific also informed broader Eurocentric stories about how Indigenous people were impediments to the European quest for gold and riches and about how they threatened the establishment of settler societies after the late sixteenth century.6 Such narratives tell us more about how Europeans incorporated their cultural preoccupation with necrophagia/cannibalism and superimposed those anxieties onto their perceptions of Indigenous American, Polynesian, Micronesian, and Australian Aboriginal culinary and cultural traditions.7

When Europeans traveled across the Atlantic Ocean and began exploring and settling the Americas in the sixteenth century, they brought a treasury of cultural images about cannibalism. In the early sixteenth century, Western Europeans routinely associated “savages,” “wild men,” and “barbarians” with cannibalistic practices. Such people appeared in Lorenz Fries’ Carta Marina (1525) and in the writings of explorers such as Sir Walter Ralegh. “Savages” and “wild men” threatened European-based sociocultural order. In Europe, for instance, heretics and witches were routinely accused of indulging in cannibalism. In the European imaginary, “wild men” were also thought to live in the woods, far from the civilized life of the town. These “wild men” allegedly took captives—usually infant children—who would later be consumed. Eating babies was perceived as a particularly debased manifestation of their savage lifestyle in the Christian European imagination.8

Despite these European antecedents, it is the association between Native Americans and cannibalism that continues to shape how millions of Americans perceive the history of Indigenous people in the United States.9 The historian Jack Forbes (Powhatan) attacked such associations during his career by inverting the racial mythologies associated with cannibalism. In one instance, Forbes argued that the ancient Greeks and Turkish sultans castrated boys who “were equally consumed by cannibals whose high degree of derangement cannot be denied.”10

Forbes was writing against the grain of multiple centuries of racial stereotypes and cultural assumptions about Native people. Indeed, the trope of the white civilizer and the savage Indian—which the narrative of Native cannibalism served so well—continued throughout the twentieth century and persists into our own time. These powerful racial stereotypes have filtered into Native oral traditions.

Federal employees recorded just such a story in the 1930s. In an interview with a Works Project Administration employee, T. C. Carriger recalled how his wife, Pearl, believed that cannibals existed among some Native tribes. Carriger, who traced his family lineage back to the Cherokee homelands in Tennessee, was born in Kansas in 1868.

Pearl, however, wasn’t Native. She arrived in Kansas at the age of eight with her father, a white man appointed as the federal agent to the Tonkawa Indian Reservation in 1894. Pearl grew up playing with Native children and hearing Indigenous stories. Despite seeing the Tonkawa as “the truest friends,” she continued to filter stories about them through a racial imagination shaped by popular media images of “savage” Indians and “treacherous” warriors. T. C. recalled that his wife often remembered the stories and gossip of the old-time Tonkawa women that convinced her that “they were once a cannibal tribe of people.”11

In the twenty-first century, racial slurs designed to denigrate and dismiss Native Americans persist. From the “Indian squaw” to the “Savage cannibal,” these terms remain part of public discourse in the United States. An example of such racial vilification emerged in December 2015 when a fourteen-year-old Choctaw girl was verbally attacked—grown men shouted abuse at her and called her a “squaw”—for protesting the use of Native American mascots.12 And on October 10, 2017, conservative media pundit Ben Shapiro was forced to issue a public apology after he posted a social media video depicting Native Americans engaged in cannibalism.13

The deployment of cannibalism to vilify twenty-first-century Native people is by no means a new phenomenon. Europeans and Euroamericans accused Native Americans of cannibalistic practices to justify colonial attempts to extinguish Indigenous communities and to objectify Native people. Such savages, the trope went, were so far removed from European Christianity and settler colonial civilization that the only effective way to deal with Indigenous cannibals was to annihilate the problem.14 Europeans and, later, Euroamericans imagined Indigenous communities who engaged in cannibalism to be so far beyond the pale of civilization as to be unredeemable human beings.15

This logic was circular: Native Americans were savages because they ate human flesh and people who ate human flesh were clearly savages. Significantly, the circulation of such formulations helped give meaning to the racial taxonomies that ultimately naturalized perceptions of Native Americans as “savages” and decontextualized Indian chiefdoms, tribes, and nations. In Eurocentric hands, the diversity and dynamism of Native American cultures was homogenized, reduced to a singularity: the “savage.”16

Cannibalism and Colonialism

If cultural and religious assumptions informed (and continue to inform) European and Euroamerican perceptions of cannibalistic acts among Native Americans, so too did the sensation of hunger. Hunger influenced how Europeans perceived what they called the New World, especially during the formative years of exploration and settler colonialism. All sorts of creatures, not just humans, reportedly acted on feelings of hunger and the primal urge to sustain life. In the Floridian wilderness, for example, the sixteenth-century French explorer and artist Jacques le Moyne de Morgues observed that in the sweltering tropical climate all living creatures preyed on and fed on the flesh of others. Local “crocodiles” (alligators), le Moyne wrote, were “driven by hunger, they come out of the rivers and crawl about on the islands after prey.”17

The uncomfortable sensation of hunger played havoc with the thought processes of the newly arrived Europeans. Le Moyne’s account recalled the fear of hunger that pervaded among the French in North America.18 Those fears and an inability to supply their own reliable sources of food meant that the French relied on Native peoples for food if they hoped to avoid the “extremity of hunger.”19

The shadow of hunger meant that death stalked these early European invaders in North America. In truth, though, no people—European, African, or Native American—were free from hunger’s grip. And where hungry people wasted away, rumors about cannibalism followed. Historian Bernard Bailyn observes that starvation among English colonists in the Chesapeake during the early seventeenth century gave rise to reports about settlers engaging in acts of cannibalism.20 Bailyn describes the early decades of English settler colonialism as the “barbarous years.” It was not long before the English began to accuse Native people up and down the Atlantic coast of cannibalism.21

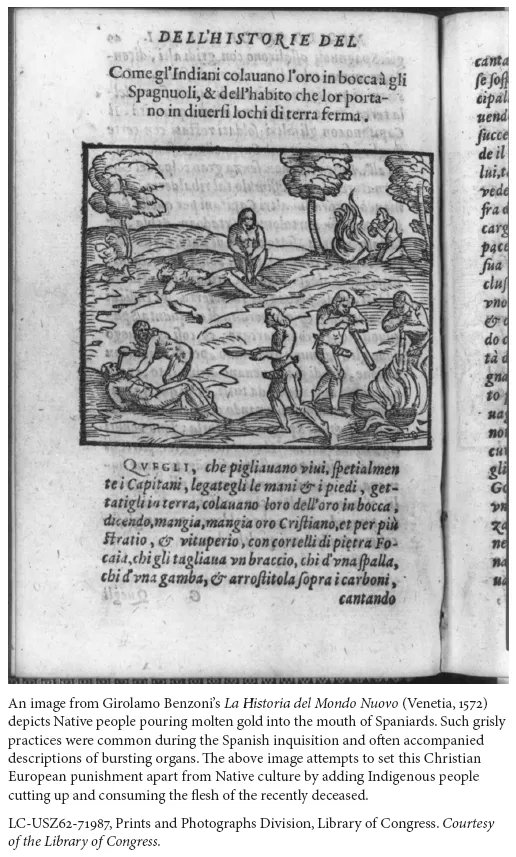

The English were not the first to develop and refine their narratives about Native American cannibalism. The Spanish made reports of Indian cannibalism decades before the English arrived in the Chesapeake and New England. Spanish explorers, such as Cortés in the early 1500s, identified Native peoples as perpetrators of sins of the flesh that ranged from cannibalism to sodomy. Framing Native Americans as savages who were given to excesses of the flesh proved that they simply weren’t equipped to live in civil societies governed by laws and political structures. Such arguments were fictions, to be sure, but they served Spanish colonizers well as they refined their legal and cultural arguments for Native dispossession and colonial expansion.22

Sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Spanish explorers, missionaries, and colonial officials began building an archive of colonial knowledge that informed the logics of Christian conversion (or Hispanicization), labor exploitation, or territorial dispossession. Woven into this archive were dramatic accounts of cannibalistic practices among the Indigenous people. In Florida, for example, accounts of the Apalachee engaging in practices such as ritual sacrifice and cannibalism, especially during times of war, became a mainstay of Spanish ethnographic knowledge.23

Similarly, French explorers and missionaries insisted that they had repeatedly heard stories of Native people engaging in cannibalism on ceremonial occasions.24 For example, Jesuit missionaries took great interest in Algonkian folklore pertaining to Kiwakwe, the “Cannibal Giant.”25 Although Algonkian narratives about cannibalism reflect a concern about social order, just as they did in Native American oral traditions throughout the Southeast, missionaries often viewed such stories as reminders of the urgency of their work and the need to save Indian “souls.”26

Europeans’ curiosity about Native cultures and their desire to convert souls all too often turned to suspicion about the meaning of those cultures and the intentions of Indigenous chiefs and warriors. Such feelings were magnified by colonial anxieties about the u...