![]()

1

Gender and Trauma since 1900

Paula A. Michaels and Christina Twomey

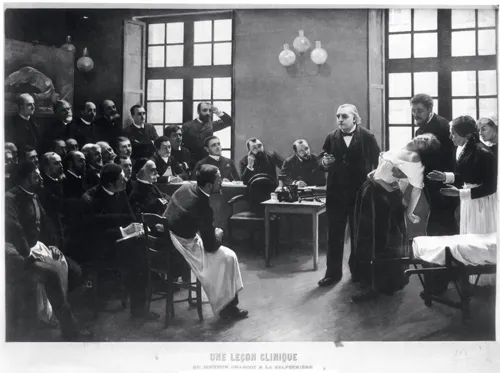

Pierre Aristide André Brouillet’s 1887 painting, Une leçon clinique à la Salpêtrière, centres on Jean-Martin Charcot, whose work is widely seen as the starting point for our modern understanding of psychological trauma. It depicts Charcot demonstrating a hysterical fit induced by hypnosis to a lecture theatre of rapt, male physicians. Like those of Charcot’s audience, the viewer’s eyes gravitate to the patient, Marie ‘Blanche’ Wittmann. Unconscious and supported by Charcot’s assistant, her white blouse and pale flesh contrast with the black sea of men’s suits. Only one small detail betrays the psychological struggle raging within her limp body: a taut, flexed fist arches back sharply. Wittmann is portrayed here experiencing one of her fits, which included falls, violent convulsions, facial contortions and delirium.1 After a childhood and early adulthood of physical and sexual abuse, Wittmann had come into the care of Charcot at his famed Paris hospital, Salpêtrière, where she became his star patient. Power in this image, as in real life, is drawn along gendered lines, though not always as clearly as they might initially appear. Wittmann’s performance of hysteria was dissected and inscribed with meaning by men whose power over her lay in their medical gaze. Charcot owed his fame and fortune in large part to Wittmann and other women, whom he displayed to his colleagues to argue that hysteria was based in the nervous system, and not in the womb. In return, Wittmann received greater safety and security than she had previously known in her troubled life. Their relationship has been described as a ‘partnership’.2 Upon Charcot’s death, Salpêtrière continued to be a haven for Wittmann, who worked as a photographic and radiological assistant; her attacks ceased (Figure 1.1).3

FIGURE 1.1 André Brouillet, Une leçon clinique à la Salpêtrière, [A Clinical Lesson at the Salpêtrière], 1887.

By theorizing that hysteria constituted a disorder of the nervous system, and not women’s reproductive organs, Charcot opened the possibility that men, too, could suffer from this malady. His lectures sometimes presented cases of male hysterics, although the disorder continued to be associated primarily with women.4 But if the image of Wittmann in Une leçon clinique à la Salpêtrière is the most iconic and enduring representation of female trauma, then it is surely the First World War combat veteran who stands as her male corollary and a ‘central and recurring image of trauma’.5 Popular culture and historical scholarship are replete with explorations of psychologically wounded soldiers who struggled to come to terms with the terrible things they endured and perpetrated at the front. Among the most well-known figures, immortalized in memoir, novels and film, are two poets – one seasoned, one a novice – and a psychiatrist, who converged at Craiglockhart War Hospital, near Edinburgh, during the First World War. Siegfried Sassoon took a public stand against the war; through the intercession of his friend and fellow poet Robert Graves, he avoided a military tribunal but found himself punished and discredited through institutionalization for shell shock at Craiglockhart. There he met aspiring poet Wilfred Owen, one of many young men battling wartime demons. From his work with men like Owen and Sassoon, Craiglockart psychiatrist W. H. R. Rivers began to formulate a theory of combat neurosis based on his interpretation of Sigmund Freud’s writing.6

This twinned imagery of trauma – the female survivor of domestic violence and sexual assault, and the male combat veteran – weaves its way through the history of psychological suffering. Despite women’s centrality to this history and the fact that they are more likely than men to suffer from trauma, women are marginalized in the research into, funding for, and popular perceptions of trauma.7 The story of our modern conceptualization of trauma is typically told as a straight line from shell shock in the First World War, through combat neurosis in the Second World War, to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), which psychiatrists formulated as a diagnostic category in the wake of the Vietnam War. Women are often erased entirely from this master narrative. Although scholars repeatedly point to the essential role feminist activists against domestic violence and sexual assault played in the formulation and acceptance of PTSD, women’s place in this history is occluded in the collective consciousness by an overwhelming focus on combat veterans, almost all of whom are men.8 Even studies that attend to how gender shapes trauma typically cordon off men’s wartime stories from women’s narratives, both in conflict zones and in peacetime.9

This book takes a step towards reconciling what has largely been two siloed conversations about the traumatic experiences of men and of women. Through eleven case studies drawn from both the Global North and South, and across the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, we examine trauma in war and peace with an eye towards the role of gender. The subjects include characters familiar in earlier literature on trauma – soldiers, prisoners of war, refugees, the victims of sexual offences – as well as those less often the focus of attention in such scholarship: humanitarians, domestic servants, birthing mothers, civilian witnesses to massacre, women who suffered from depression. How does putting these histories in dialogue shed light on the persistent marginalization of women in the master narrative of trauma? In juxtaposing histories around the globe, what can we learn about the sociocultural situatedness of gender and trauma? What change over time is evident, given transformations over the last century in women’s political and social position? To explore these concerns, we must first clarify what we mean by trauma. We then briefly recount the medical and social history of trauma, with particular attention to how it intersects with gender. Finally, we articulate how the ensuing chapters speak to the need to bridge the scholarly divide between studies on male combat veterans and female civilians. A more holistic, inclusive approach refocuses attention on the common encounter with violence that underpins traumatic experience regardless of sex but is endemic to women’s everyday lives.

What is trauma?

Because of the multiple and contentious ways that the term ‘trauma’ is used, it is necessary to define what we mean at the outset. Until the nineteenth century, the word referred solely to physical injury. Investigations in the budding fields of neurology and, later, psychiatry, stretched the definition to encompass, as literary scholar Cathy Caruth pithily puts it, ‘a wound inflicted not upon the body, but upon the mind’.10 Trauma is today understood typically to be the experience of a catastrophic, often sudden occurrence that overwhelms an individual’s psychological capacity to process the event. Mental health professionals continue to seek clarity about who is at greatest risk and why. Psychiatrist Bessel A. van der Kolk and others argue that victims often experience feeling unable to respond to a life-threatening event with either fight or flight, and, instead, freeze in response, trapped in an unresolved, untenable psychic state. However, that the initial event – such as a serious car accident, sexual assault, natural disaster or combat – is experienced as life-threatening is a necessary, but not sufficient, explanation for trauma’s lingering effects.11

In the aftermath of the event, sufferers of post-traumatic stress experience certain common symptoms, which can include

1. recurrent , involuntary and intrusive memories of the event;

2. recurrent distressing dreams;

3. dissociative reactions (e.g. flashbacks);

4. intense or prolonged psychological distress at exposure to internal or external cues that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event and

5. marked physiological reactions to internal or external cues that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event(s).12

Thus, a traumatic event (or the perception of it) inaugurates a vicious circle: the creation of a distressing memory, which in turn ‘provokes the autonomous nervous system and the survival response (fight, flight, freeze), causing difficulty sleeping, irritability, an exaggerated startle reflex, hypervigilance, difficulty concentrating, and motor restlessness. The victim adapts to the distressful memory and consequent arousal through symptomatic avoidance and numbing’.13

The modern understanding of psychological trauma and its impact has changed over time. Over the last 150 years, many names have been used to describe this phenomenon: hysteria, shell shock, war neurosis, combat neurosis, traumatic neurosis, battle fatigue. Rebecca Jo Plant’s chapter, for example, charts what was at stake in the approved nomenclature of psychological distress among US forces during the Second World War. Family members, military authorities and soldiers themselves challenged psychiatrists about terminology, such as ‘psychoneurosis’, that they perceived as encapsulating negative implications about masculinity, capability and integrity. The constellation of symptoms seen as indicative of the disorder, too, have undergone continual revision. Flashbacks, which are at present understood as a hallmark of PTSD, were virtually never reported among combat veterans of the First and Second World Wars. Even since PTSD’s 1980 introduction into the psychiatric lexicon, some symptoms have ...