1

A Framework for Analysing General Principles

I.INTRODUCTION: A TETRAHEDRAL FRAMEWORK

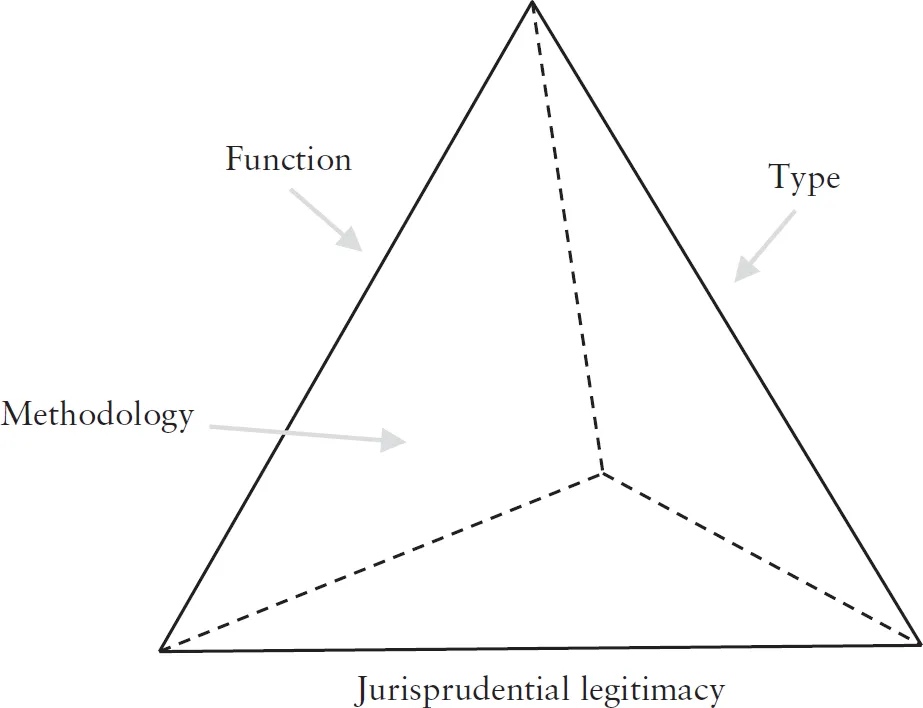

To build a model of General Principles, we initially need to know three things: first, the role that General Principles play (their function); second, the type of content that can form a General Principle (their type); and, third, how they are found (their methodology).

The fourth aspect that must be considered is the jurisprudential underpinning of the source’s legitimacy. If we think of the first three questions as the three vertical sides of a tetrahedron, the fourth aspect is the horizontal floor: touching and informing all other aspects.

Figure 1.1 General Principles: A Tetrahedral Framework

As will be seen in this book, these four aspects are interrelated. A certain characterisation of the judicial legitimacy of the source often leads to assumptions about the other three aspects as well. Too often these interrelated aspects are not separated out and the underlying assumptions interrogated. Accordingly, the analysis in this book attempts to partition the four elements of the source. This ensures that the final model of General Principles is not coloured by unwritten assumptions about any of the four aspects. Doing so also offers up some explanation, as discussed later in chapter 7, why different national schools of international law1 offer contrasting views of General Principles.

This chapter sets out a brief introduction to each of the four sides of the tetrahedron. It will engage with the work of commentators only to the extent necessary to illustrate the different possibilities under each aspect of the source. It purposefully does not dive too deeply into these theoretical discussion to avoid prejudging the analysis that follows. The aim of this chapter is provide a structure of analysis only: the following chapters will apply this structure to the jurisprudence of the PCIJ, ICJ, other international courts and tribunals, and then turn to scholarly commentary of the source.

II.JURISPRUDENTIAL LEGITIMACY: A BRIEF CONSIDERATION OF POSITIVISM AND NATURAL LAW

Martti Koskenniemi describes the ‘material’ aspect of a source of international law as

the explanation of sources as the history, cause or basis from which law ‘emerges’. This (‘material’) aspect of sources seeks to provide for the law’s legitimacy, pointing to its origin in a legislative process, natural reason, a principle of justice or policy that resonates with our political sensibility and that we usually take as good reason for applying the standard based on it.2

It is this same material aspect that is termed jurisdictional legitimacy in this book. Within Koskenniemi’s explanation, the tensions between a positivist and natural law approach to sources are immediately obvious. While ‘legislative process’ indicates a positivist approach, ‘natural reason’ or ‘justice and policy’ suggest a natural law basis.

The key distinction between positivism and natural law for the purpose of this book is necessarily a reductionist one. In short, natural law posits that there are ‘true and valid standards of right conduct’,3 and that that law is binding because of its inherent morality and justice.4 A natural law conception of General Principles sees jurisprudential legitimacy tied up in the content of the norm itself. This immediately prioritises type over methodology, and impacts the function of the source as certain norms may be more binding (more moral) than others.

In contrast, employment of a positivist Hartian rule of recognition5 accords jurisprudential legitimacy based on the process by which the General Principle is found. Under strict legal positivism, law is a social reality and is created (or ‘posited’), not discovered.6 Positivist laws are no more or less valid than each other: a law is either valid or it is not.7 Methodology is now foregrounded, as it is the methodology that confers validity, and consideration of type is restricted to simply what type of norm can satisfy the prescribed legitimacy granting methodology – beyond this, the content of the General Principle is irrelevant. Function is also affected, as each norm is equally valid and none can override another.

Of course, modern conceptions of international law are not confined to contrasts between pure natural law and strict positivism. As Fuller argued, positivism reaches a limit when determining what gives the law-making process – the rule of recognition – itself legitimacy. Unless the process gains legitimacy by itself being created by a valid law-making process (thereby creating an infinite regress), its fundamental nature must instead be gained from the validity of its content.8 Kelsen’s ‘basic norm’, or grundnorm,9 provides this root source that imbues the law-making process with its power. Kelsen states that ‘the basic norm is not valid because it has been created in a certain way, but its validity is assumed by virtue of its content’.10

What makes up the grundnorm of international law will influence how we understand General Principles: the implication of a grundnorm based in consent is discussed in the next section on function. Thus positivist law itself has a natural law basis: an ultimate foundation in content rather than procedure. This book does not seek to maintain a bright-line distinction between positivism and natural law, and recognises that the two necessarily co-mingle. Yet one can still characterise a position as (more or less) positivist or (more or less) one of natural law. In the context of General Principles, the characterisation of the jurisprudential legitimacy can also follow the same lines. This in turn impacts on the rest of the tetrahedral framework.

III.FUNCTION: A BINDING SOURCE OF INTERNATIONAL LAW?

Sources of international law can be either formal11 or subsidiary12 sources. A formal source gives rise to binding norms of international law.13 Of the sources contained in Article 38 of the ICJ Statute, both convention14 and custom15 are formal sources of law.16 If the requirements either for a treaty to be made (the express consent of those countries entering into it)17 or for custom to be formed (the state practice and opinio juris of a vast majority of affected states)18 are met then a new norm of law is created. In the case of conventions, that norm is binding only on those countries who entered into the treaty.19 For customary law, the norm is binding on all states in the international community,20 with the exception of ‘persistent objectors’ states.21 In contrast, a subsidiary source of law does not create international norms but is a way of determining the content of norms. The opinions of publicists and decisions of national courts22 are subsidiary sources.23 An opinion of a publicist, no matter how qualified, does not in itself give rise to a binding norm of international law. Such opinion, however, may be instrumental in determining the precise content of a norm of international law, or in providing documentary evidence of such a norm.24

Unlike the other three sources under Article 38(1), some contention remains as to the function of Article 38(1)(c). Some commentators consider the source as norm-creating only in the context of the ICJ and not part of international law per se,25 or merely subsidiary, serving to help interpret norms established by convention or custom.26 The more widely held view is that General Principles are a formal source of law. This is often tempered by the restriction that they will only be applied if treaty or custom is absent27 (although this restriction is not universally adopted).28 This view often sees the primary role of General Principles as filling gaps in international law.29 While many commentators choose one view, others see General Principles as a hybrid source – simultaneously formal and subsidiary in effect.30

The link between jurisprudential legitimacy and func...