- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

After completing the final version of his general theory of relativity in November 1915, Albert Einstein wrote a book about relativity for a popular audience. His intention was 'to give an exact insight into the theory of relativity to those readers who, from a general scientific and philosophical point of view, are interested in the theory, but who are not conversant with the mathematical apparatus of theoretical physics.' The book remains one of the most lucid explanations of the special and general theories ever written. In the early 1920s alone, it was translated into ten languages, and fifteen editions in the original German appeared over the course of Einstein's lifetime. The theory of relativity enriched physics and astronomy during the 20th century.

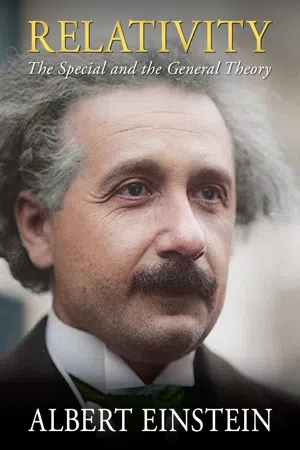

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Albert Einstein, a gentleman who belongs to the elite league of Newton, Tesla, Maxwell and considered to be the greatest scientist of 20th century. Born in Germany, and worked as a clerk in the patent office before revolutionizing the world of physics, Einstein with his incredible achievements in scientific world has become synonymous to the word genius. He provided the world, two of the most brilliant concepts of physics through his theories of relativity, and won the Noble Prize in Physics for his work on Photoelectric Effect, which eventually become the foundation stone for tremendous developments in electronic technologies and quantum theory. Einstein is not only celebrated as the greatest physicists of all the time but he was also a wonderful human being and philosopher. World War II and presence of Adolf Hitler in Germany forced him to stay in the US during the period, where he consistently tried hard to warn and evade the application of nuclear fission as a weapon of mass destruction. He collaborated and interacted with many extraordinary minds of his time contributing to the world of physics and humanity as a whole. His unmatched intellectual imagination collaged with his immense interest in music, philosophy and humanity makes him the greatest personality that scientific world and mankind have ever seen.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Table of contents

- Preface

- Note to the Fifteenth Edition

- Part 1

- 1. Physical Meaning of Geometrical Propositions

- 2. The System of Co-ordinates

- 3. Space and Time in Classical Mechanics

- 4. The Galileian System of Co-ordinates

- 5. The Principle of Relativity

- 6. The Theorem of the Addition of Velocities Employed in Classical Mechanics

- 7. The Apparent Incompatibility of the Law of Propagation of Light with the Principle of Relativity

- 8. On the Idea of Time in Physics

- 9. The Relativity of Simultaneity

- 10. On the Relativity of the Conception of Distance

- 11. The Lorentz Transformation

- 12. The Behaviour of Measuring Rods and Clocks in Motion

- 13. Theorem of the Addition of Velocities. The Experiment of Fizeau

- 14. The Heuristic Value of the Theory of Relativity

- 15. General Results of the Theory

- 16. Experience and the Special Theory of Relativity

- 17. Minkowski’s Four-Dimensional Space

- Part 2

- 18. Special and General Principle of Relativity

- 19. The Gravitational Field

- 20. The Equality of Inertial and Gravitational Mass as an Argument for the General Postulate of Relativity

- 21. In What Respects are the Foundations of Classical Mechanics and of the Special Theory of Relativity Unsatisfactory?

- 22. A Few Inferences from the General Principle of Relativity

- 23. Behaviour of Clocks and Measuring-Rods on a Rotating Body of Reference

- 24. Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Continuum

- 25. Gaussian Co-ordinates

- 26. The Space-Time Continuum of the Special Theory of Relativity Considered as a Euclidean Continuum

- 27. The Space-Time Continuum of the General Theory of Relativity is not a Euclidean Continuum

- 28. Exact Formulation of the General Principle of Relativity

- 29. The Solution of the Problem of Gravitation on the Basis of the General Principle of Relativity

- Part 3

- 30. Cosmological Difficulties of Newton’s Theory

- 31. The Possibility of a ‘Finite’ and Yet ‘Unbounded’ Universe

- 32. The Structure of Space According to the General Theory of Relativity

- Appendices

- Appendix I

- Appendix II

- Appendix III

- Appendix IV

- Appendix V