When you enter the world of David Cronenberg, there are no bad men with knives in the closet. No one pops up out of the bathtub after a certain drowning. The wind doesn’t rattle the windows or make the curtains billow like death shrouds. No. The horror in the world of David Cronenberg is not the easy, external horror of the slasher, but the far creepier, insidious horror of the self, of self-consciousness. I think; therefore, I might not be.

It’s out of such a disturbing state of mind (and body) that Cronenberg has fashioned his work. First came two provocative but pretentious “underground” science-fiction films in the late sixties, Stereo and Crimes of the Future, in which Cronenberg already displayed an interest in sexuality, control, and the social order. His long wait for a commercial feature—funding is difficult in Canada and often involves the government—ended with They Came from Within, where the repressed residents of a sterile high-rise become infected with parasites that sex them up in most unusual ways. A full-scale debate in Canada’s Parliament about the suitability of government support for such a film followed (no doubt to Cronenberg’s dismay and delight) and indicated what he was up against in the Great White North. Enter former Ivory Snow girl and porn star Marilyn Chambers, sporting an underarm phallic spike in Rabid, an entertaining essay in which, as in so many of Cronenberg’s works, cutting-edge science and somatic desire perform a romantically tragic pas de deux. Next, Cronenberg made a skidding detour onto the drag strip for the formulaic, forgettable Fast Company.

It wasn’t until the 1980s that he really hit stride. The Brood was a minimasterpiece about the horror of the fraying family; Scanners brought Cronenberg his drive-in audience, with its famous exploding head and sci-fi subtext; Videodrome was a complicated, polyoptic exploration of the connection between image, power, and flesh, starring James Woods in an emotionally intricate role; and The Dead Zone found Cronenberg boiling down the Stephen King bestseller and extracting the best performance of Christopher Walken’s career. And then The Fly put him squarely over the top. Featuring Jeff Goldblum and Geena Davis, Cronenberg’s reworking of the laughable little 1950s original was masterful: tight, vicious, disgusting, metaphorically rich, and intellectually rigorous, it was slamming yet subtle, like the best of all his work. After The Fly, he turned down the temperature with Dead Ringers, a stainless-steel-on-skin story of self-destructive identical twin gynecologists (both played brilliantly by Jeremy Irons), which scraped to the core of the problem of identity—how we separate self from other. Indeed, considering these six films, an argument can be made for Cronenberg as the most consistently interesting filmmaker of the 1980s.

He’d been scheming, dreaming, and fretting over his next work for many years—the unfilmable film, Naked Lunch. William Burroughs was always one of Cronenberg’s greatest influences (indeed, much of his thematic imagery strongly parallels that of Burroughs), and Naked Lunch provided him with his long-wished-for fusion of their visions. It’s quite a strange film, hardly the free-for-all that is the Burroughs novel. Rather, it’s dry as dust, slow as sun, bristly in its intelligence, and unsettling in its aura: it’s like a visit to the mental dentist. It is also one of the few pictures that generously rewards—and almost, like Videodrome—necessitates a second screening.

Born in Toronto in 1943, Cronenberg was gearing up for a career in science when English stole his brain at the University of Toronto. He wrote a few stories that won him some attention and shot his first experimental shorts. He made do without film school. Early in his career, Cronenberg was lumped together with a number of other young horror filmmakers, most notably George Romero and John Carpenter, but they’ve been inappropriate company for at least the last ten years. In addition to his feature films, he has done work for Canadian television and a couple of terrific commercials for Nike and Cadbury’s Caramilk chocolate bars.

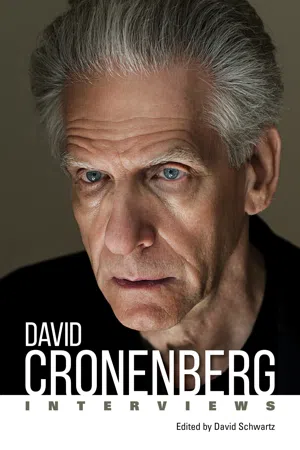

I met with Cronenberg in November 1991 in Toronto, where he still makes his pictures and lives, quietly (when he’s not racing cars), with his second wife and his three children. We talked in his small, spartan office as the snow swirled outside. The man himself is calm, thoughtful, and focused; he’s deadly serious but not at all deadly.

SESSION ONE

David Breskin: Let’s go back to the beginning. There’s very little written about your childhood and your family. I’d like you to describe it.

David Cronenberg: I was brought up in a kind of immigrant section of Toronto: Jews that had not yet moved out to the suburbs, Turks, Italians, Greeks. My father was a bibliophile and a writer, and my house was always full of books. Literally, walls made out of books. I never really saw the real walls of the house because we had so many books; there were actually corridors made out of books. To me this was all perfectly normal, of course, since it was there from first consciousness. And he was also very much the music buff, and a bit of a gadget freak. I remember we had an Altec speaker that was much taller than I ever was. It must have been a studio-size speaker. He had a Quad amplifier. Down a street, around the corner was the record store, and my father was always down there, previewing records. And my mother was a pianist—for the ballet, for choirs, for violinists and their teachers, and opera singers and their teachers, who would come to the house.

I was exposed to culture, but I was never into studying it. So I know tons of music in my head note for note, but I don’t know who composed it and have no idea who played it. They weren’t just into that kind of culture though; they were both very eclectic. I remember an album of recordings from all over the world. The original African recording of “The Lion Sleeps Tonight,” which is better than anything that ever came after. Fantastic, incredible. And old blues records. And folk. So it was a very eclectic culture, not just classical.

Breskin: What were your folks like as parents?

Cronenberg: Great. They were very sweet. Very supportive. I think that has always been there for me, underneath. Very approving, very easy, very sweet people.

Breskin: Did they want you to be a scientist?

Cronenberg: Well, the truth is, they wanted me to be whatever I wanted to be. I’m sure they had discussions at night, very worried about my latest girlfriend or my latest philosophy of life, whatever—but I wasn’t really exposed to much negativity, I have to say. Basically, if I decided I wanted to go into science my father would immediately present me with twenty books on biochemistry, and be enthusiastic. And if a year later I decided to drop out of science—which I did—and went into English, then we would talk about literary criticism, and I’d get twenty books on literary criticism. And he’d be equally excited by that. I never felt I had to please them. It seemed like whatever I did pleased them.

Breskin: Sounds ideal.

Cronenberg: It was, it was. I mean, obviously, life being life and humans being humans, there was angst and anguish that they had to deal with that I didn’t know much about. They basically did not lay that on me at all. I mean, my father’s mother-in-law was in the house, my grandmother, and she had a leg amputated, so I grew up with this wonderful wheelchair in the house that I could do wheelies in and go up and down the halls in. I know that must have caused huge stress and strain—because she was a mother-in-law and an invalid, and in this very tiny house, and there’s not much money and all of that—but I didn’t know all that. Nobody screamed and yelled.

Breskin: It’s been said that children live out the unexpressed emotions of their parents.

Cronenberg: I don’t think that’s true. I think children have a desire for things to be wonderful, and given half a chance, they will experience them that way. I don’t think they’re looking for bad times. That’s my experience of it. I can be back there in a dash. I can be back living at home, instantly.

Breskin: Well, I flash on you living there with this grandmother figure and her amputated leg, and think of your body consciousness—

Cronenberg: Well, it’s not impossible. I mean, this leg is something I would see. We’d talk about it. She’d tell me about the phantom leg, how she’d feel pain where her leg used to be. It was all pretty mysterious at the time. Although I’m not sure she was the most sweet, forgiving woman at the time, she was a real grandmother to me. She wasn’t a huge part of my life, but I definitely do remember that stuff. There was not a sense of sickness about her, despite the amputated leg. The wheelchair was great. I couldn’t see why anybody wouldn’t want to wheel around in that. On a conscious level, I was pretty oblivious to the anguish that must have been hers.

Breskin: Maybe the wheelchair was your first car.

Cronenberg: For sure, it was. I had a red tricycle, which I preferred, because I could take that outside.

Breskin: What about your sibs? You have a sister named Denise?

Cronenberg: That’s right. She’s been the costume designer on the last few movies. She’s four years older than I am. So we had that kind of relationship. When she became a teenager and I wasn’t, I didn’t see her that much because she’d be out doing teenage-type things. We used to put on plays at the house; she’d organize those. I still remember we did Little Red Riding Hood. I was the hunter that popped up at the end and shot the wolf at the last minute. I had to stay behind the piano hiding for the whole thing. We had seats set up in the living room, for people to come in and watch the play.

Breskin: What were your childhood obsessions? I know you had the car bug fairly early, and then also the bug bug—

Cronenberg: Well, the bug bug I think preceded the cars. In fact, I do remember a period when I was really down on cars because I was into animals. I hated to see squirrels run over by ’53 Buicks because there’s not much left of the squirrel after that. So there was definitely a period when I was not crazy about cars, and my father didn’t have a car; we didn’t have a car in the family. I’d walk everywhere. Everything I needed was accessible by walking or bicycle. I remember my father had a car for about ten minutes once. I remember he bought it, and we were driving around the corner. And we had to get out—the car was dead. I never saw it again. My mother never drove, and my father almost never drove.

Breskin: The first 8-mm film you ever shot as a teenager—your train arriving in the train station, as it were—was of auto racing, right?

Cronenberg: That’s correct. Not only that, but a guy, a CBC producer, was killed in the first race that I shot, and I have that on film. He rolled his Triumph TR3 in the chicane at Harewood Acres.

Breskin: So in your very first film you unified your obsession with death, your love of technology, and your ambivalence about TV!

Cronenberg: Probably. (laughs) Maybe just producers in general.

Breskin: Every kid has fears. It’s almost a cliché that your horror is the horror of the adult and not of the child, but I’m wondering, what was the dark stuff of your childhood?

Cronenberg: I think it was pretty garden-variety stuff. The scariest movie I ever saw as a kid was Blue Lagoon, with Jean Simmons. That was the movie that kept me up with the lights on for at least a week, maybe more. Normally, I liked the dark. I wasn’t a kid that was afraid of the dark. But this was separation from your parents—that was the scary thing. And Bambi was terrifying. And Babar the Elephant was terrifying. The Blue Lagoon was terrifying because it was about two kids on a boat, and the boat catches fire, and the boat sinks. And the two kids are on this island with this drunken sailor who eventually falls out of a skull-shaped cave and dies, and so the two kids are totally alone and have to invent their own culture. That was the part that was terrifying—separation from parents. And when people get hysterical now about children and terror and film, they really are looking at it from an adult point of view. I think kids can take a lot of things that adults find terrifying, but what is almost universally terrifying for a kid is the idea of being separated from his parents.

Breskin: You’ve had to live out that fear in two different ways: first, in going through the death of both your parents, and second, in being separated from your child when your first marriage ended. Let’s talk first about your parents because I know that was a real shaper. When did your father die?

Cronenberg: Well, I don’t know. This is the most bizarre thing. I actually don’t—I can’t remember the dates of my parents’ deaths. But my mother died … my father died first. My father had been sick, had this mysterious illness, but my mother had always been absolutely healthy. I never remember her even having a cold. Not ever. I was in London when I got a phone call from my sister, totally hysterical and destroyed, saying that both of my parents were in the hospital. Now, my father wasn’t a surprise, but my mother, that was a total shock. She’d had a stroke, and I think it was the stress of my father’s illness.

Breskin: He had an illness where he couldn’t process calcium; his bones were so brittle he could break a rib turning over in bed.

Cronenberg: Yeah, that was just one of the more horrifying aspects of it. It was a kind of general disintegration. At a certain point his body just started to let go. Suddenly I had two parents in the hospital, and I had to come back. And it was just sort of downhill from there. My father died. My mother was relatively okay for roughly another ten years, but she was never totally right. She had heart trouble.

Breskin: Did you have to take care of her?

Cronenberg: Yeah, basically. She could live on...