The Friday Mosque in the City

Liminality, Ritual, and Politics

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

The Friday Mosque in the City

Liminality, Ritual, and Politics

About this book

Concerned with the relationship between Friday mosque and city in the Islamic context. Focusing particularly on the Friday mosque, the book aims at exploring the concept of liminal(ity) in spatial terms and discuss it in terms of the relationship between the Friday mosque and its surrounding urban context. Transition spaces/zones between the mosque and the urban context are discussed through the case studies from various contexts. In doing so, the manuscript reveals different forms of liminality in spatial sense.

Considers widely-studied topics such as the 'Friday mosque' or the 'Islamic city' through a fresh new lens, critically examining each case study in its own spatial urban and socio-cultural context. While these two well-known themes – concepts that once defined the field – have been widely studied by historians of Islamic architecture and urbanism, this collection specifically addresses the functional and spatial ambiguity or liminality between these spaces. Thus, instead of addressing the Friday mosque as the central signifier of the 'Islamic city', the articles in this volume provide evidence that there was (and continues to be) a tremendous variety in the way architectural borders became fluid in and around Friday mosques across the Islamic geography, from Cordoba to Jerusalem and from London to Lahore.

By historicizing different cases and contributing to our knowledge of the way human agency through ritual and politics shaped the physical and social fabric of the city, the papers collectively challenge the generalizing and reductionist tendencies in earlier scholarship. The disciplinary approaches are varied, and include archaeology, art history, history, epigraphy and architecture.

The original approach in the book, addressing of the topic of liminality from different points of view and in different periods, creates a fresh approach that invites students and scholars to think deeply about the imbrication of congregational mosques in the daily life of the cities that host them. Moreover, in considering mosque and city together, the mosque appears as a living space subject to change and history and made with political and social purpose, rather than as a holy space disconnected from the rest of the world.

Traditional studies of mosques focus on architecture and aesthetic language and try to establish a lineal development of the building typology connected to the history of Islam across different territories. The present study offers an alternative (though not competing) perspective where locality and politics play a major role in the materialization of the congregational mosque as a religious and communal space. The wide historical frame enables comparison of congregational mosques in different historical periods: it is particularly a strong contrast to see how the liminality of the mosque changes between the early and classical periods of Islam on one side and the more contemporary times on the other. The consideration of diverging cultural, political and sectarian settings is another interesting element of comparison.

Primary market will include scholars, academics and students working on or studying Islamic studies, particularly Islamic history, Islamic architecture and Islamic archaeology.

Also of relevance to architectural historians, architects, art historians, city planners, city historians, urban designers, architectural critics, historians, sociologists, archeologists, and those interested in religious studies, and in archaeology of religion.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Section I

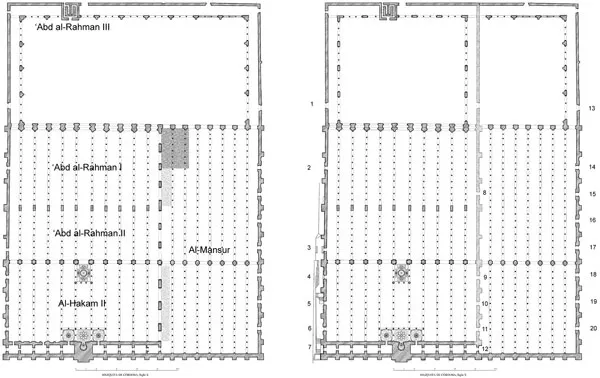

Liminal Spaces in the Great Mosque of Cordoba: Urban Meaning and Politico-Liturgical Practices

2. St. Sebastian or Viziers door (foundational inscription from Muhammad I period)

3. St. Michael door (no inscriptions)

4. Door of the Holy Spirit (Q. 40:3)

5. Palace or Bishop door (Q. 40:12–14, 40:16–17)

6. St. Ildefonso door (no inscriptions)

7. The sabat doors

8. Door of the ‘Abd al-Rahman II phase, found in the excavations (no inscriptions)

9. Door of the Saint Martha Altar (Q. 3:19)

10. Door of the St. Sebastian Altar (no inscriptions)

11. Door of the St. John the Baptist Altar (Q. 16:90)

12. The ‘Punto’ door or Treasure Gate (Q. 19:35)

13. Saint Catherine door (no inscriptions)

14. San Juan door (Q. 3:191–92)

15. Baptistery door (Q. 59:21–23)

16. St. Nicholas door (Q. 14:52 and 39:53)

17. Door of The Conception (Q. 36:78–79 and 43:68–71)

18. St. Joseph gate (Q. 3:1–4)

19. Magdalena gate (Q. 33:56 + Q.112)

The Doors of the Great Mosque of Cordoba: Written Sources, Qur’anic inscriptions, and Architectural Remains

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- A Note on Transliteration

- Introduction

- Section I: Spatial Liminalities: Walls, Enclosures, and Beyond

- Section II: Creating New Destinations, Constructing New Sacreds

- Section III: Liminality and Negotiating Modernity

- Author Biographies

- Index