![]()

Chapter One

INDEPENDENT OF THE WORLD

Alachua is one of the older counties in Florida, created by the Florida territorial government in 1824, twenty-one years before Florida achieved statehood. Tucked securely into North Florida, the landmass of the original county was considerably larger than it is today. Long and narrow, it was bounded by the Georgia state line to the north, the Suwannee River to the west, and an ungainly dogleg to the south that stretched to the gulf at Charlotte Harbor.

Figure 1. Finley’s Map of Florida 1827. Courtesy of Florida Memory

The Suwannee marks the boundary of West and East Florida, and Alachua made up a good slice of East Florida so long that the topography changes from top to bottom. The Georgia side of the county was more attached to the plantation district of Middle Florida, while the southern end was more palmetto than live oak, still inhabited by the Seminole and their allies.

On early maps the central part of the sprawling county was described as high rolling pine, or less attractively, as pine barrens, and closer to the coast, the flatwoods. The aquifer was higher then, bursting the seams of the fragile limestone to flow aboveground in shallow ponds and sinks so wide that when the water line withdrew, the lakes became prairies.

Wildlife was abundant, and indigenous tribes had lived on the banks of the springs and gulf of Alachua County for eons. The tribes included the Timucuan, and further east, the Potanom. The very name, Alachua, was a derivation of a Muskogee word for sinkhole, or big jug.

By the time Florida gained statehood in 1845, the remnant aboriginal tribes had long been extinguished by European conquest and even more deadly, European disease. Even the Spanish, who’d been in Florida since the 1500s, who’d established missions along the Santa Fe River and at San Felasco, and vast cattle ranching on the prairie at Arredondo, were mostly gone. The county’s most recent inhabitants, the Seminole, had been driven south of Fort King by the ongoing action of the Second Seminole War.

The remaining population of Alachua County was sparse, hardy, and ethnically diverse. They were a melting pot of the descendants of the Indians, Europeans, and Africans who’d survived brutal wars, brutal heat and a host of feared diseases to eke out a hardscrabble life in the trackless, and nearly lawless wilderness.

In 1842, Congress opened the floodgates to immigration to the area when it passed the Armed Occupation and Settlement Act for the express purpose of luring white settlers to the area. The qualifications of the Act were simple: anyone who built a home, cultivated five acres, and promised to resist the Seminole for five years received 160 acres of land and rations for a year from the federal government.

The offer of free land was, as always, enticing, and yeomen farmers from across the South began a steady trek to East Florida, along with cotton planters from Georgia and the Lowcountry of South Carolina, whose cotton plantations had depleted the land for other farming. The climate and soil of East Florida wasn’t considered as lush as the red dirt of the plantation belt of Middle Florida, but it had been found to be amendable to growing Sea Island cotton, a long-strand cotton that brought a premium price at market.

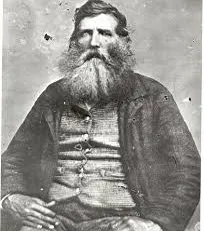

A South Carolina planter, overseer and cattleman named Phillip B. H. Dudley was one of those immigrants, arriving in Alachua County in the early 1850s.

Figure 2. Phillip Benjamin Harvey Dudley, 1870. Courtesy Florida Memory

Born outside of Charleston in 1818, Dudley had begun his working life as an accountant and overseer of enslaved laborers at the Legare Plantation in St. Johns, South Carolina. He later owned his own plantation, possibly from his wife’s family, called Walnut Hill.When Dudley first came to Florida he worked in the lucrative cattle trade, and as an overseer of a two hundred-slave cotton plantation in the area of Fort Clarke.

Converting the high rolling pine barrens of Western Alachua County into viable cotton land required hard, relentless labor and a cheap supply of it, which South Carolina planters like Dudley introduced to the East Florida wilderness in the form of enslaved Black labor. As an overseer, Dudley’s job was to extract labor from the plantation owner’s slaves. Overseers were sometimes referred to as drivers, which was an apt description of their job—to drive their enslaved laborers, men, women, and children, to long hours, faster work and higher production.

Overseers were valued for their toughness, their ability to maintain order, and their efficiency in administering rigid, violent discipline to their master’s slaves. Punishment was harsh and could include whipping, confinement in sweat boxes, branding, mutilation, or being sold on the auction block. There is no written record of P. B. H. Dudley’s precise treatment of the enslaved laborers under his management, but his rapid rise from accountant, to overseer, to plantation owner suggests that he was effective in the work of managing enslaved laborers, which would have included a willingness to administer brutal intimidation and punishment.

Dudley prospered in central Alachua County, accumulating his own slaves and land in the area of Archer and Arredondo. He served as a trustee for the fledgling Alachua County school board, and worked for the county road commission. His job with the highway commission was similar to his work on the plantation. As an overseer, he was paid to oversee enslaved Blacks in the backbreaking labor of hacking a primitive highway through the dense scrub, swamp and pine of Western Alachua County between Archer and the county seat at Newnansville. It was in his position as a road commissioner that Dudley found three hundred choice acres of high rolling pine and hammock six miles west of Fort Clarke, where he planned to establish his own Florida plantation.

On the 1860 federal census, Dudley was listed as living on his new property with his wife, Mary, and three children—Virginia, Ben and Joanna—with his post office listed as Archer. He had nine hundred sixty acres and thirty enslaved laborers, making him one of the more prominent planters in Alachua County.

The names of enslaved laborers were not listed on the census, but age, sex and race are recorded. On the Federal Slave Schedule, taken July 6, 1860, Dudley owned six female enslaved laborers, three of whom were age eighteen. The rest were male laborers and children ranging in age from age eight to eighty-two.

All thirty of the Dudley slaves were listed as mulatto, which was unusual at the time, but not unknown. Some Florida slaveowners, such as Duval County’s Zephaniah Kingsley Jr., were known to prefer mixed race, then called mulatto slaves. Some of Kingsley’s mixed race slaves were his own children, a product of forced slave concubinage, which was a common practice of the day. It is possible that Dudley, like Kingsley, bred his own enslaved women, though unlike Kingsley, Dudley was never known to have freed or acknowledged any slave mistresses or children.

The house that P. B. H. Dudley’s slaves built on his Gainesville Road property was by modern standards primitive; by frontier standards wholly adequate; a double-pen dog trot—basically two rooms covered by a single roof with a breezeway between—that was sufficient for homestead. Dudley’s plans to build a larger, Georgian-style plantation house were interrupted by Florida’s secession from the Union in 1861, which Dudley, a slaveowner and ardent secessionist, fully supported. There has been some debate between Florida historians and local Black historians as to whether Dudley’s farm had its genesis as a slave plantation, or a more simple dirt farm, owing to the fact that Dudley’s plantation house was built after 1865.

Myrtle Dudley confirms that enslaved Black laborers built his original dog-trot structure on the Old Gainesville Road, and has recollections of slaves who lived on the property, including the family of Becky Perkins, who are reflected on the federal census. Before and after the Civil War, both P. B. H. Dudley and his son Ben were referred to in local newspapers as “prominent planters,” and their capital investment in enslaved labor was far more extensive that the more common small-holding dirt farmer. The State of Florida may split hairs on the exact definition of plantation, but P. B. H. Dudley’s three hundred acres were bought by a slaveowner, and cleared by his enslaved labor. Had the war not intervened, he would have had them cultivate Sea Island cotton.

True to his South Carolina roots, Dudley was instrumental in establishing Company C, 7th Florida Infantry, CSA, where he served as captain, an honorific that he would carry until his death in 1881. His company saw action in the western theatre, from Chickamauga to Nashville, before he furloughed out in 1863 after a life-threatening bout with dysentery. When he recovered, he returned to action for the final skirmishes in Florida in Olustee, the defense of Gainesville, and the Battle of Otter Creek.

In an oral history taken in 1992, Myrtle Dudley recounted her grandfather’s Civil War service: “. . . Grandpa and them hitched up his slaves, got his own slaves up, and was made captain of his own army team, and he went to the War Between the States. He w...