![]()

PART ONE

AUDITION

![]()

![]()

WEDNESDAY 14 DECEMBER 2016

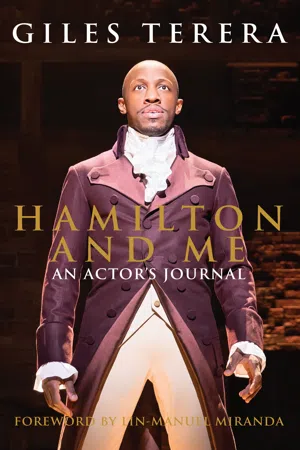

Today it’s my fortieth birthday and I was offered the role of Aaron Burr in Hamilton.

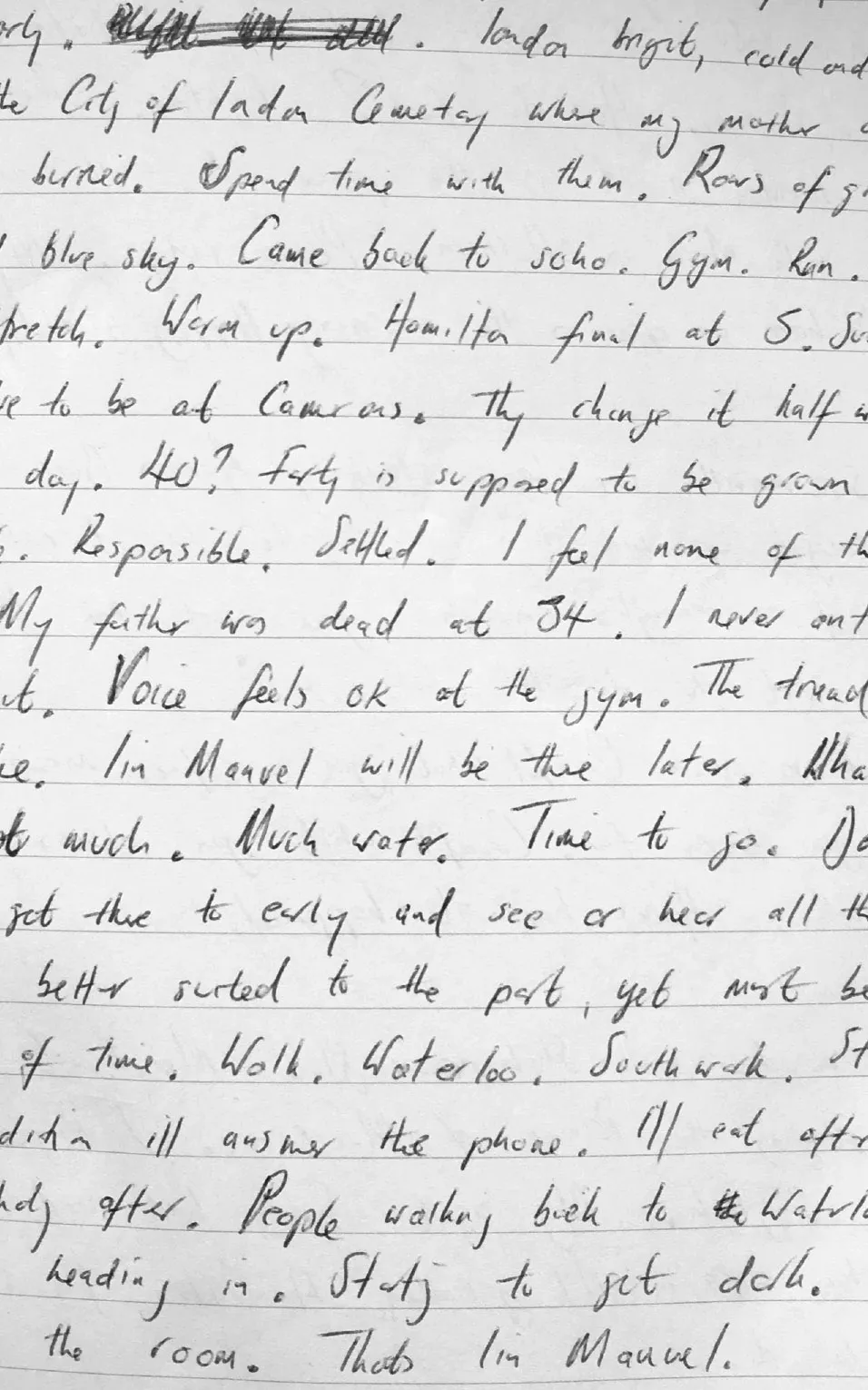

I woke early. London—bright, cold, clear. I go to the City of London Cemetery where my mother and father are buried. Spend time with them. Rows of gravestones and blue sky. I come back home to Soho. Gym. Run. Thirty mins. Stretch. Warm up. Hamilton final audition is at 5 p.m. Southwark. It was due to be at the Cameron Mackintosh offices in Bloomsbury. They switch it halfway through the day to the main audition rooms in Southwark.

Forty? Forty is supposed to be grown up. Respectable. Responsible. Settled. I feel none of these things. My father was dead at thirty-four. I never anticipated passing that.

Voice feels okay at the gym. The treadmill doesn’t lie. Lin-Manuel will be there later. Haven’t met him yet. Wonder what he’ll be like? Don’t think about it. What to eat? Not much. Much water. Time to go. Don’t want to be there too early and see or hear all the other gentlemen better suited to the part than me, yet I must be there in good time. Walk. Waterloo. Southwark. Still sun. Just. Birthday almost gone. After the audition I’ll answer the phone. I’ll eat after. Think about birthday after.

People walking back to Waterloo Station from work. Me heading in. Nearly dark. Walk in the room. That’s Lin-Manuel. There’s Tommy. Alex. It’s good to see them again. Cameron. Apart from to identify each face, my mind is concentrated on one thing only: Aaron Burr. All the preparing. Learning. Working. Researching. Trying. Singing. All of that serves to get you to this point. Yes. But now. Now it’s time to let go.

An hour later I’m walking back across Waterloo Bridge. Stars. The river moves silently. How do I feel? Lighter. The bright, blurry London night is a beautiful place to walk alone. Dinner with Mark in Holborn. Phone rings as soon as we sit down. My agent, Simon: ‘We’ll have an offer first thing in the morning. Happy birthday.’

Rewind.

Six months prior to that night I was rehearsing a tour with Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre. Merchant of Venice. I was playing the Prince of Morocco. Jonathan Pryce playing Shylock. We were starting in Liverpool. The week before we were to travel up there, my agent had messaged me and said, ‘You should listen to this new show that everyone’s talking about in New York. Hamilton.’

Oddly enough, the previous night, a friend of mine had texted me from New York saying, ‘I’ve just seen the greatest show I’ve ever seen in my life. Hamilton. You have to be in it.’ The proximity of these two messages unnerved me. I hadn’t heard the show, but I’d heard of it. Wasn’t it hip hop? They’ll want someone hip hop. Not me. Was the excuse I shot back. But I could tell it was an excuse. Covering up for what? I knew nothing about the piece. Sometimes bells just ring. And when they do they can scare. ‘You should listen to it,’ Simon said.

‘Cameron’s bringing it over next year. They want to see you for it.’

‘Which part?’ I said.

‘Aaron Burr.’

‘Who’s Aaron Burr?’

It takes me two hesitant days to go and buy the cast recording. Something told me to listen to it from my own hands rather than YouTube. Plus it gave me a chance to stall.

The same day I go and buy the CD I bump into a friend of mine in Covent Garden. ‘Are you going to be in Hamilton? You have to play that part, the narrator.’ I didn’t tell her I had the album in my bag.

I go home. ‘HAMILTON. AN AMERICAN MUSICAL.’ Double CD. I unwrap it and put it in the player. My finger pauses over the play button. What’s wrong with me? What is this? PLAY.

Halfway through the first song it’s clear I am in the presence of something extraordinary, and by halfway through the second song I know that I know this man, Aaron Burr. Somehow. Like I know myself.

When I get to the end of the album I go back to the beginning and listen to the whole thing again. Again, when I get to the end, it makes me cry. I text my agent: ‘This is the greatest thing I’ve ever heard.’ And I meant it. Lyric after lyric. Rhyme after rhyme. Melody after stunning melody. Such moving wit. Such intelligence. All in the service of a breathtaking story. And this man. ‘I think I have to play this part.’ That certainty is what terrifies. That is what makes us want to run and hide. It’s rare, maybe once or twice in your life, when you just feel something. Something which can’t immediately be explained. A bell just rings. A clarity occurs and the thing is there in front of you.

Achieving . . . ah, now that’s the hard part. What to do? Acknowledge the bell. Then roll your sleeves up and work like a bastard.

Simon said, ‘Well, good, because Cameron’s bringing it over and they want to see you for it. You’re going to be away on tour when they audition so I’ve set something up for New York for when you’re out there. Start learning those songs.’

So I get to work. Every second I can find, I am learning this material. Going over and going over and going over. Never was I so happy as when, on my morning run round Liverpool’s Albert Dock, I was able to get through the first verse of ‘The Room Where It Happens’.

That was the start of July. Two weeks later we are performing Merchant of Venice at Lincoln Center in New York.

I hadn’t told anyone I was auditioning, but a few days before we arrived in America I got found out. Jolyon, a friend in the Merchant cast, caught me practising ‘Dear Theodosia’ in the corridor on a tea break from rehearsals. Busted. So I had to confess. ‘You’re fucking shitting me!’ I told him I was auditioning and they were letting me see the show when we were in NY and I had another ticket if he wanted to come.

The morning we arrive in Manhattan I head out for a run round Central Park. Jolyon is trying to give up smoking so says he’ll come along. I suggest a little route: up as far as the reservoir and then back down the east side to the zoo. Fine. We make it up to the reservoir and start coming down. The sun is blazing even at 10 a.m. and after a while we’re both pouring sweat. So I tell him we can stop. ‘Nah, not yet. I’m fine. Keep going.’ But after another five minutes I start to worry for him.

‘Fuck you.’ He gasps. ‘Let’s keep going. No pain, no gain.’

Five minutes later he finally says, ‘Okay. That’s good. I’m done when you are.’

I say, ‘Okay, why don’t we go as far as that statue over there?’

Two or three hundred yards later we gasp our way to a standstill by the large white statue we’d seen on the grass. He leans against it, looks up and says, ‘Look!’ The plinth simply reads ‘HAMILTON’. We look up and there he is, looking down at us. One hand on his chest and the other holding papers.

Two days later we watched the show. I think Lin and Leslie Odom Jr. had only just left the show. I had been swimming in this piece for three weeks straight, but nothing prepared me for actually seeing it. We sort of staggered out onto the sidewalk at the intermission. The July sun just setting, and I remember thinking, what am I seeing?

Next day, after rehearsals and before the show, I jump in a cab, head downtown and meet Alex Lacamoire. Hamilton’s musical director. I’m a little scared, but I needn’t have been—he is amazing and generous and open and funny and encouraging. I sing the material I’d spent the last few weeks trying to learn during Merchant rehearsals. It seems to go well. We have fun. So much so that we run over and now I’m late. I have to be back at Lincoln Center in ten minutes for Merchant performance number three.

I run back up Eighth Avenue. In rush hour. In the late-July dog-day afternoon heat. But I am happy. I got through the songs and didn’t disgrace myself. Alex even said I did a good job. As I run up Eighth Avenue, sweating, I think to myself, if I look left down one of these streets—48th Street or 50th Street—I might just catch a glimpse of the trees of Weehawken across the river. But no time for that. The Prince of Morocco is waiting.

Next morning I wake up to a message from Simon: ‘They liked you. They want you to go back today.’

So I did. Tommy Kail is there this time. Director. If I was scared to meet Alex, I’m even more scared to meet Tommy. I mean, whoever put this thing together must be a scary motherfucker. The fact that it’s so packed with ideas, thoughts, journeys, yet each one delivered and realised with perfect clarity. That kind of storytelling ability doesn’t stroll by every day. Whoever came up with this is going to have to be an intimidating presence.

As it happens, Tommy is cool. Equally as open and interested as Alex. He is slight. A mop of curly hair. Big smile. Watching eyes. A lean, coiled energy. He smiles and points at Alex: ‘Well, he told me you were good, so let’s go.’ I do the same material. It didn’t feel as settled as the day before, but I hadn’t expected to have to come back. And the tag team of Aaron Burr and the Prince of Morocco had been kicking my ass all across the Atlantic. But Tommy seems happy. We talk. He’s interested in who I am. Where I’m from. My parents. We part with a ‘pleasure to meet you’.

The following week our tour moves to Washington, D.C. The 2016 Presidential Election is in full swing. Hillary or Trump? We make a trip to the White House. The Obamas are apparently in when we go. The building loaded with history. Being in that place proves a prodigious experience. I think of the building of a nation. And those upon whose backs it was built.

Then I hear nothing from Hamilton for a while. ‘They said they’ll see you at the finals in December. Keep on top of the material,’ Simon says. I’m not so sure. ‘They’ll be getting the original cast over for London, surely? I wouldn’t complain about that at all. They can have their pick. It’s Hamilton.’

After D.C. our tour journeys to Chicago for two weeks. After that, China for a month and a half. Then back to the Globe for a month, and finally to Italy. Close in Venice. Nothing from Hamilton.

While we were in China I met up with a school friend of mine, Wai Wing. He and his wife showed me around Hong Kong on one of our afternoons off. I told him I’d been visiting the various temples of whichever city we were in, and he took me to one nearby. We lit incense and he explained to me different aspects of the many shrines there.

At the end of our visit, my friend sat me down in front of an old man who took the remaining incense sticks from my hand and squinted at them for a while, turning them over in his palm. He then told me, through Wai Wing’s interpretation, that I had recently met someone of whom I should be wary, because although he was very brilliant and intelligent, he couldn’t be trusted. I wasn’t sure who he was talking about.

After the tour I arrive back in London. Dreaming about Aaron Burr. Seeing him in my mind’s eye. Hearing him. So much of what people say to or about him in the show, people have said to me. I feel as if I know him. Like I know myself. This also strikes at the fear element. To peer at oneself is a very exposing thing. ‘Stay on top of the material,’ Simon keeps saying.

Autumn submits to winter. Still nothing from Hamilton. Simon: ‘They’ll see you at the final. Stay on top of it.’ I do. I do what I know: work. I go to my mentor and singing teacher Nettie Battam down in Brixton. She’s worked with everyone from Maria Callas to most of the musical theatre performers of the eighties and nineties. She gives me a funny look when I tell her it’s a hip hop show, but when she makes me play her the music she claps, throws her head back and lets out a massive laugh: ‘But, my darling, this is an opera.’

I find myself asking questions about this man. I began to read more about him. All I can find. Which is a lot less than the other Founding Fathers. The more I find, the more I want to know.

At the same time, part of me wants to resist getting too attached. What if ? What if ? If they’d wanted me they would have said something. Right? It’s been four months. I hadn’t wanted to tell anyone I’d auditioned. Not even my sisters. Why jinx it?

Then.The RSC call. Titus Andronicus. Would I come in for the role of Aaron the Moor? In all Shakespeare this is the one role where I thought I’d love to play that some day. And now is the first time in my life I feel as if I’d actually be able to. I go in and audition. They offer me the part. Aaron at the RSC.

Simon says, ‘It clashes with Hamilton.’

‘But we’ve heard nothing from them.’

‘We have. They’ll see you at the finals next month. I keep telling you.’

Aaron in Stratford or Aaron in Yorktown. In my waking hours there’s no contest, of course, but once again the cool fear of getting one’s hopes up for a part which feels in your DNA makes you flinch. What if ? What if ? Aaron offered or Aaron to reach for. Aaron to climb? Aaron to become?

‘Can the RSC hold off for two weeks?’

‘No. You have to make a decision now. Call me in the morning.’

I walk. Sit silently and I ask. Not to get the part— but for courage to hang on. Next morning I message Simon: ‘Let’s wait for it.’

That was mid-November. The final audition is December. December 14th. My birthday. Every day for those few weeks I get up and work. Sing. Read. Search. Try. Learn. Work. Sing. Read. Watch. Work. Wait.

And so, on December 14, Simon calls and says, ‘We’ll have an offer first thing in the morning. Happy birthday.’

I try to speak but no sound is coming out. He says, ‘Don’t speak. I’m going to hang up now before I start to cry. I’ll speak to you in the morning . . . Aaron Burr.’ The only words which form before hanging up: ‘Thank you.’

Now, any actor will tell you that after you get a job first comes the fleeting moment of elation, then comes the panic. Holy shit. Now how do I do this? What do I really know about this man, Aaron Burr? That he befriends Hamilton and somehow ends up taking his life. What do I actually know about the American Revolution? It’s too late to turn back now.

It was as if this person, this man who ...