- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Barry McKenzie Movies

About this book

An illuminating tribute to Bruce Beresford's subversive and hilarious film The Adventures of Barry McKenzie, and its equally riotous sequel, Barry McKenzie Holds His Own, by cultural historian and documentary filmmaker, Tony Moore.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Barry McKenzie Movies by Tony Moore in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Film History & Criticism

1

The Adventures of Barry McKenzie

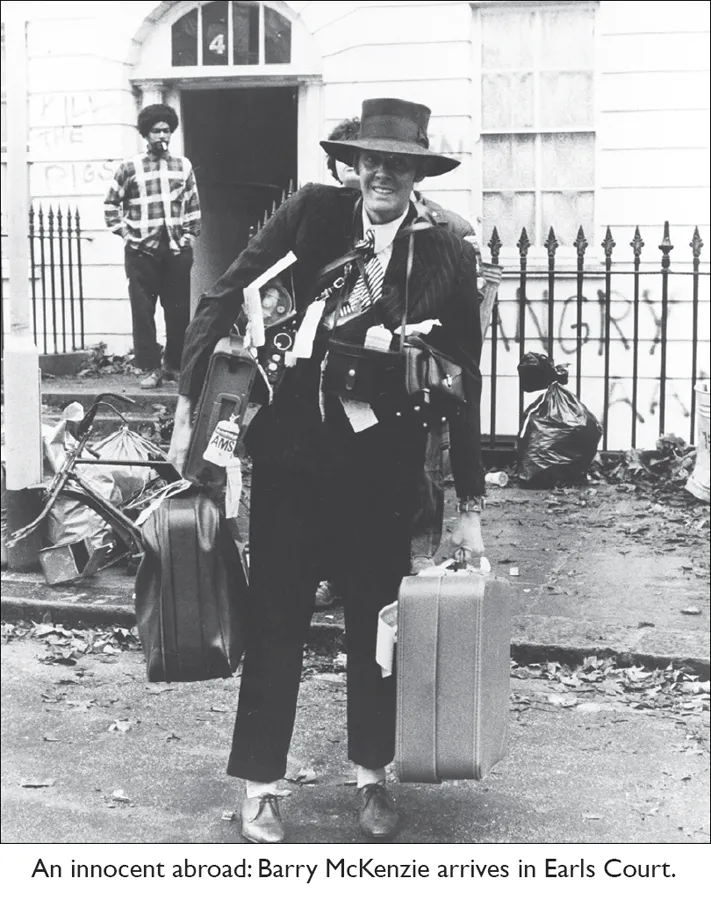

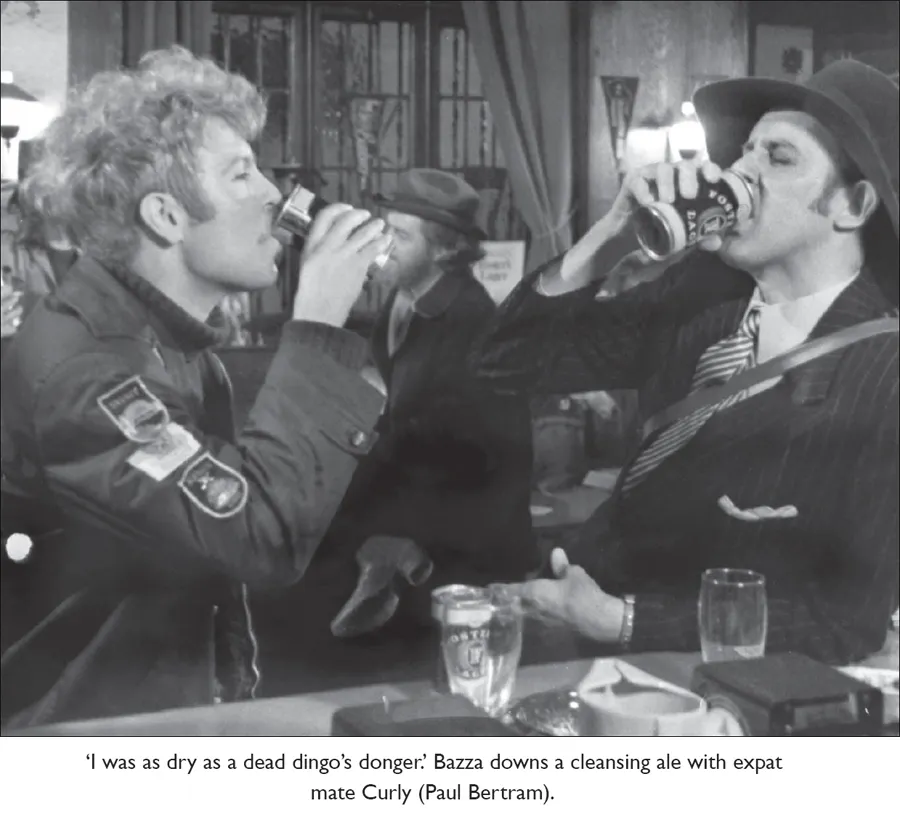

The Adventures of Barry McKenzie begins in Sydney with the reading of Barry’s father’s will that decrees the son will only inherit if he returns to England to absorb the culture of the mother country. With his fussy Aunty Edna (Barry Humphries) as chaperone, Barry, festooned with cameras and a Qantas bag, boards the national carrier bound for London. He discovers a bleak and Dickensian England of squalid lodgings, downcast immigrants and rapacious hustlers. Beresford favoured shooting London exteriors on overcast days and took care to have garbage strewn on the streetscape to create a grey mise en scène that played up to the Australian prejudice of miserable weather and decay. Once ensconced in the Australian ghetto of Earls Court with his mate Curly (Paul Bertram) and bibulous expats (notably a lairish cameo by Beresford) and a steady supply of foaming Fosters, Barry has a succession of encounters with English men and women who alternately want to fleece, promote, exploit, shag, marry, psychoanalyse, arrest or fight him (and occasionally several of these at once).

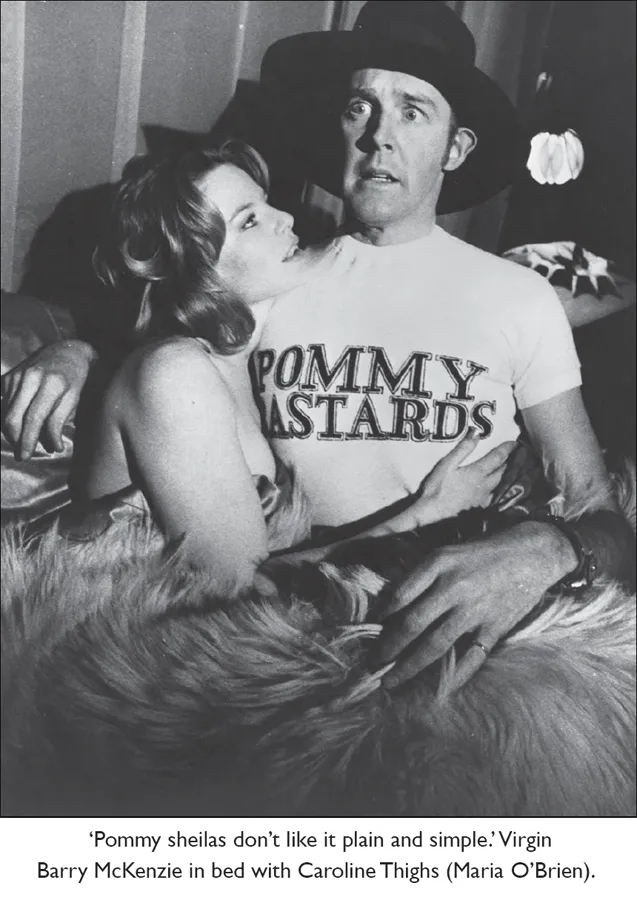

For his part, Barry considers most of the natives to be either ‘pommy bastards’ or ‘poofs’ and frequently both. Though the ‘potato peelers’ (sheilas) are fair game for ‘a knee trembler’, Bazza fears that they ‘don’t like it plain and simple’, and his sexual inexperience leads him from one amorous misadventure to another. Despite all his linguistic sexual bravado, Barry is a virgin, and will remain one. Ever the incorrigible ocker, Barry continually misreads the social signals to great comic effect, but is also game for new experiences that invariably lead him into trouble. Our hero leaves mounting chaos in his wake, climaxing in the exposure of his ‘old fella’ live on a BBC TV program about the artistic renaissance in Australia.

The film is episodic, a loosely connected series of standout sketches in the manner of the comic strip from which it came. Beresford, who confessed to only ever liking three comic strips himself—Prince Valiant, Doonesbury and Barry McKenzie—happily admits sitting down with the comics and lifting ‘scenes, characters and dialogue for the film script’. This narrative structure has a fine pedigree in the literary genre of the picaresque. The Adventures of Barry McKenzie echoes the eighteenth-century novels Tom Jones and Moll Flanders where a young hero sets out into the wide world to encounter a passing parade of eccentrics, villains, misfortunes and, of course, sexual adventures—all of which have their origins in the very origins of the novel: Cervantes’ seventeenth-century Spanish masterpiece, Don Quixote.

Much of the humour in Adventures comes from the effortless way the charming but vulgar Bazza moves up and down the British social register, mixing with upper-class fops, trendy TV producers, home county Tories, Eastend gangsters, a Jewish psychiatrist and hippies. These characters are presented as English grotesques and are played by a who’s who of British comedy—for laughs but also to showcase some of the baser elements of human nature and contemporary social malaise that Humphries disdained. The counterpoint to this exotic menagerie is the Australian monstrosity Edna Everage, safe and smug in her suburban carapace.

Spike Milligan plays the oily, nameless slum landlord who is all but covered in cobwebs. He leads Bazza past prostitutes and ne’er-do-wells to a dog box that requires a pound note in a meter just to keep the light running. Of all the characters Barry meets it is the Gorts, an in-bred, inward-looking family of Tory dysfunctionals, who take the cake. Mrs Gort (Avice Landon) looks like the Queen but is actually a glimpse into the Thatcherite future. A social climbing ‘Little Englander’ chauvinist, she disinfects her mail because the postman is black, has a Winston Churchill figurine mug and pretends she has a cook. She assumes that Barry is one of ‘those wealthy Australian shareholders’ and plots to marry him off to her put-upon, thumb-sucking Young Conservative daughter, Sarah (Jenny Tomasin). The balding, tweedy hubby Ronald (played by Ealing Film stalwart Dennis Price) is a panting masochist who dresses up as a schoolboy and tries to persuade Barry to discipline him.

If Humphries thought little of philistine conservatives he thought even less of hippies. A trio of alternative musos who claim to ‘just roam around the country making the simple, unaffected music working people like’ are revealed to be greedy, violent, Machiavellian fame fuckers. Their leader, Hoot (Barry Humphries), is an American-accented hippy conman who wants to exploit Barry’s musical talents and hisses things like ‘if we can’t make bread out of an authentic Australian folk singer I’ll get out of this racket’. Hospitalised following a brawl, Bazza falls into the clutches of another inspired grotesque, Jewish shrink Dr de Lamphrey (Humphries again) who is an amalgam of the psychiatrists Humphries was forced to endure while confined to various sanitaria for his drinking problems and depression in the late 1960s. While Bazza is strapped to a table like Frankenstein’s monster, de Lamphrey scuttles around the floor trying to decipher his patient’s exotic argot and asking whether he can see patterns in the carpet until a ‘technicolour yawn’ stops him in his tracks. When Barry visits Leslie (Mary Anne Severne), a young family friend, he mistakes her suave, suit-wearing lesbian lover Claude (Judith Furse) for a man. Ironically, she is the most gentleman-like person England has yet thrown at Barry. But Claude is also a bit of a lech, and can’t keep her wandering eye off Barry’s aunty.

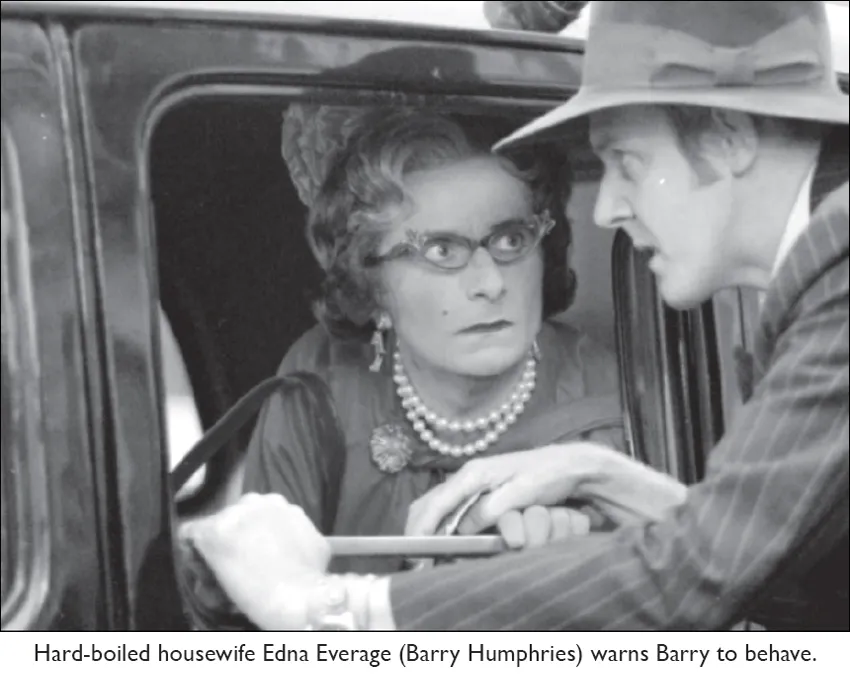

Presiding over this freak show is, of course, the Moonee Ponds monster, Edna Everage, familiar to Australian audiences from her appearances on stage and TV throughout the 1960s. She is a pantomime suburban housewife with garish make-up and clothes, frightening in her smothering respectability and philistinism. It was Beresford who insisted that Edna—who had nothing to do with the comic strip—be catapulted into the movie, and it was an inspired decision. She is a dominant but not unappealing character throughout both films, and the only person who can bring Barry to heel. In a topsy-turvy conceit Edna alternately nags and mollycoddles her strapping nephew as if he were a small child. The subtext is transparent: Australian men never grow up and need looking after by mother figures, whether they be actual mothers, or wives or, in Bazza’s case, aunties. Given that Humphries was a boy during the war it may well have seemed to him that women rule the roost. If, as some film theorists think, this castration anxiety on the part of post-War men gave America the femmes fatale of film noir, then it gave Australia Edna Everage.

The Edna of the Bazza films is a very different woman to the celebrity megastar of today. Back then she was the same housewife Australian audiences had first met in 1956 when she appeared on TV at its birth as a volunteer Olympics hostess, driving an official to apopolexy as she primly rejected all nationalities offered as billets for her Moonee Ponds home. By the early ’70s her dress is inappropriately lairy for a woman of her age. Unlike most of the discreet English women she meets, Edna is over the top and forever intruding. Like Bazza, she has no sex life, lamenting her husband Norm’s prostate operation. But as an Aunty she finds consolation in doting on Barry, cooking lamingtons for him and his mates. As well as keeping an eye on her nephew, she hopes to take in ‘the olde worlde charm’ of England but is condescending about the standard of British amenities. For Edna, England has never recovered from the blitz and so she hands out parcels of dripping as her family had during the (fictitious) ‘Fat for Britain Drive’. Edna is a constant reminder that no matter how cosmopolitan their adventures, the cloying, philistine suburbs are never far away. Except that, throughout the Bazza movies, Edna’s metamorphosis into a smart-mouthed dame with a good line in put-downs is well under way. She may be a housewife but she’s also hard boiled, like a baited lolly.10

Humphries recently described Bazza as ‘an innocent adrift treading bravely the moral quicksands of the swinging London of his day’.11 Adventures follows in the tradition of Voltaire’s Candide and fish-out-of-water films like Mr Smith Goes to Washington (1939) and Ninotchka (1939), playing with the tensions and misunderstandings between provincial hicks and the metropolis. An Australian film precursor was Ken Hall’s comedy, It Isn’t Done (1937) in which a humble farmer (Cecil Kellaway) inherits a baronial estate and moves the family to England, to the chagrin of the neighbouring aristocrats. An obvious successor is Crocodile Dundee (1986). The corruption of the innocent is a popular theme in Australian memoirs and many, including Humphries’ own autobiography, More Please, recycle this trope, in which a young man from the provinces or the suburbs is inducted into the secrets of the bohemian demimonde. But whereas the heroes in these rites-of-passage stories discover the mysteries of the metropolis through sex, Barry’s desires are continually frustrated, his growth to manhood stunted by sexual dysfunction and emotional Peter Panism.

Like many frustrated men, Barry never stops talking about sex, but it’s the sex talk of schoolyard braggers, amusing coming from a six-foot bloke. Because of his awkwardness with women, his fumbled liaisons always end in farce. When a vacuous and buxom blonde actress named Caroline Thighs (Maria O’Brien) throws herself at Barry he gets it all wrong after consulting the Karma Sutra. Unable to find a herbal aphrodisiac at the local Indian grocery store he anoints his loins in curried beef with disastrous results. After leaving a Young Conservative dance early with the comely Sarah Gort, he is unable to make the first move, even though one of his mates (played by a young John Clarke) advises him that ‘some of those sheilas that don’t look so hot are great little performers’. His pursuit of hippy waif Blanche (Julie Covington) ends in a rumble as her jealous switchblade-wielding boyfriend goes for Barry’s gonads. Gobsmacked by the feminine vision of Leslie when she frocks up to elude the police, the gauche Bazza is moved to declare, ‘Kiss my bum if that sheila wouldn’t bang like a dunny door’, and cops a well-deserved slap across the face. McKenzie ends the film as he began it, a boy untouched by amorous hands, snug in his auntie’s embrace.

Adventures defies easy pigeonholing as just a shallow ‘ocker comedy’. Its creators set out to critique society and shock audiences while producing a commercial success. The filmmakers had served their apprenticeships within the artistic bohemian fringe in Australia and Britain, but by the 1970s they wanted to entertain mainstream audiences. Humphries had already tasted success as a performer and Beresford had had his fill of underground filmmaking purity when commissioning at the BFI. They were not the first Australian artists to combine bohemian identities and tastes with careers in the entertainment industry and nor would they be the last. The most entertaining art comes from a cross fertilization of the margins and the mainstream, and this is what makes this film so interesting for me.

Humphries’ theatrical experiences in the 1960s had been diverse and they make a deep impression on the film. His early talent for humorous monologues had been nurtured in revue comedy at universities and companies like the Phillip Street Revue in Sydney. At London’s alternative Establishment Club in the early 1960s Humphries began to absorb the mood of Britain’s cerebral comedy boom. The intellectual side of Humphries’ humour is apparent in the film’s play with issues like art, Australian identity, expatriation and sexual diversity. Threaded through the beer and chunder are cultural references for those in the know. Barry Crocker recounts sitting through Adventures with a guffawing Germaine Greer, who had to explain to him arcane lesbian and literary allusions.12 It’s not, however, an obsession with matters of the mind for which Adventures is best remembered.

Humphries had long sought to make an art form of bodily excretions. His one-man shows in the ’60s increasingly trod the same fine line between the salon and the toilet that would characterise Adventures. What gave the film an edge was an enthusiasm to transgress mainstream middle-class taste born out of Humphries’ experiments with dada and surrealism and Beresford’s underground film work. Humphries had exhibited artworks like ‘Pus in Boots’ (a boot filled with custard) and pretended to throw up on trams using homemade vomit. One of Beresford’s earliest filmmaking experiences was as cinematographer on the student avant-garde short, It Droppeth as the Gentle Rain, which climaxes in the cast being showered in shit from the heavens.13 Both artists found that playing with the appetites and ablutions of the body could be liberating in a society emerging from a prim postwar conservatism.

You cannot avoid Bazza’s sheer physicality. Slave to his appetites, he continually sucks tubes of Fosters, showers himself and his mates in foaming geysers that ejaculate from the cans, and crams lamingtons into his mouth. When he vomits on Dr de Lamphrey, a truly gross and realistic expulsion pours from Barry’s gob and trickles down the face of the hapless shrink.14 Defending his determination to make cinematic history with this graphic ‘chunder’, Humphries insisted: ‘If you don’t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Author’s Biography

- Australian Screen Classics

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- Introduction

- The Barry McKenzie Movies

- Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Filmography

- Television

- Credits

- Copyright Details