eBook - ePub

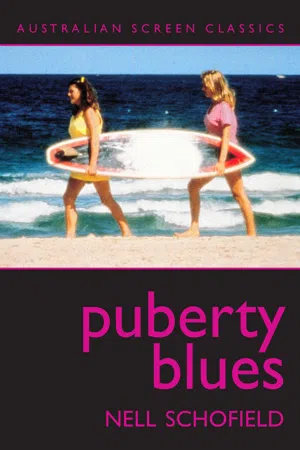

Puberty Blues

About this book

'Fish-faced moll', 'rooting machine', 'melting our tits off': with its raw, in-your-face dialogue, the film version of Gabrielle Carey and Kathy Lette's classic novel, Puberty Blues, has also become a cult classic. In this lively and honest account, writer and broadcaster Nell Schofield recalls how she won the role of Debbie and what it was like on the set. She looks at the parallels between the film, the book and her own surfside teenage years, and at the extraordinary response the film generated. It's a story as idiosyncratically Australian as the film that showed everyone who ever had any doubt that chicks can surf.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Subtopic

Radio

1

SURFIE SCRAG

It’s something I’ll never live down. Practically every week over the past two decades or so somebody comes up to me and mentions it: ‘You were in Puberty Blues! Oh my God! That film changed my life!’ Not only that. These freaks know all the best lines, like ‘fish-face moll’, ‘rootable’ and ‘you’re dropped’. And it’s not just women of my generation who flip out over the film. I recently interviewed an all-male rock band with serious street cred and the guitarist could hardly answer my questions because he was so busy raving about how cool he thought the film was. The other day a fifteen-year-old girl went all weak at the knees when she met me and her mother had to explain that the kids regularly hold Puberty Blues parties. As do older folk.

It seems that dear old Pubes has even become something of a fashion statement. Not long ago I was walking past one of those trendy street-wear stores and did a double-take when I saw a silhouette of myself and co-star Jad Capelja printed on a sexy little T-shirt with a handbag and wallet to go with it. I went in immediately to buy the matching beach towel as a souvenir. Twenty years on and a photo of two girls in the sand dunes, one carrying a surfboard, is the height of teen chic. Retro Surfie Scrag, it would appear, is the look du jour.

So why does this particular Australian film continue to strike such a resonant chord with so many diverse people? Is it the fact that it presents a youth sub-culture that they can all relate to? Is it the language, raw as a radish and unashamedly Australian, that people find so endearing? Perhaps it’s just a time capsule of Australian life in the late 1970s that people both embrace and are repelled by at the same time. Or maybe it’s the triumph of the underdog that ultimately wins them over, that classic story arc which sees the protagonists reject peer group pressure in favour of individualism? Here are a couple of factoids to mull over: Puberty Blues is listed number 41 of the top Australian films and number 17 (along with Gallipoli and The Sum of Us) on the list of Top Rating Australian Feature Films screened on television.1 But it seems the film has moved beyond these statistics into a realm that borders on cult.

Obviously there are creative technical factors that contribute to the movie’s durability too, not the least of which being the crafty direction by Bruce Beresford and lensing by his acclaimed colleague, Don McAlpine. These two men had worked together on The Adventures of Barry McKenzie and the follow up, Barry McKenzie Holds His Own, both celebrations of bad blokey behaviour and peculiar Aussie vernacular. The pair also collaborated on Don’s Party, Breaker Morant and The Club, more iconic films revelling in Australian manhood. For almost a decade before embarking on this teenage surfie saga, Beresford and McAlpine had been developing a visual language that often worked in counterpoint to the earthiness of the scripts, adding touches of poetry where on the page there was only gritty realism. For these two ‘New Wave’ filmmakers, Puberty Blues was a major departure from their usual fare. They were plunging head-on into the chick-flick genre and with all that oestrogen pumping about they had to keep a steady grip on the viewfinder.

Puberty Blues is a story about two Sydney teen babes muscling their way into a top surfie gang then busting out of it again with renewed confidence and independence. In essence, it is feminist tale; the girls initially try to fit into the narrow, stereotypical roles assigned to them but eventually realise that the whole scene ‘sucks’. In defiance, they do the unthinkable and take to the waves, invading a strictly male-dominated space. The honesty of the material and its insight into Australia’s urban surfing world is unique.

Its originality lies in the racy book of the same title by Kathy Lette and Gabrielle Carey who, aged 18, wrote a no-holds-barred account of their early teenage years and let it loose on the public, much to the delight of their fellow teens and the scandalised horror of their parents. Kathy’s mother, Val, was particularly appalled. She was the principal at a school in the Sutherland Shire where the tale is set and took it as a personal affront, an assault on her reputation. As Kathy later explained:

… the publication of Pubes must have been an excruciating embarrassment for her, especially where the pinstriped-underpanted parents were concerned. She brazened it out, but things were a little bit frosty, all right, arctic, at the time.2

These two surfie chicks told it like it was for them trying to break into the Greenhills Gang at Sydney’s Cronulla Beach; the gross initiation ceremonies, being paired with boys they’d never even met and joylessly losing their virginity in the back of panel vans at drive-ins. They disguised themselves in the characters of Debbie and Sue but few were fooled and, as Gabrielle Carey subsequently revealed, the book was ‘totally autobiographical’.3

I first read it soon after it was published in 1979 when a friend thrust it at me in the playground one day. I had already heard about the two authors. They were notorious, a wild double act lunging at life like there was no tomorrow, biting off more than they could chew and chewing like buggery. They called themselves ‘The Salami Sisters’, the idea being that they were doing something ‘spicy and meaty’. Not only had they written this outrageous book but they were also writing a column in a Sunday tabloid, the Sun Herald, called ‘A Slice of Life’ and running around the country as Spike Milligan’s self-proclaimed groupies.

Flicking through the book I could hardly believe my eyes. Not only was it rude, lewd and utterly spot-on as far as the current teen lingo went but here was the story of my life … well, not exactly, but pretty damn close. It was hilarious and horrendous all at the same time—full of things I knew only too well because I too had been drawn to the sexy, salty, sandy, sun-tanned world of the beach, only in my case it wasn’t Cronulla but Bondi. And just like the narrator in the book, Debbie Vickers, I had an inseparable bosom buddy. Debbie had Sue, I had Emma, a friend without whom I would never have dared to do half the things I did in those heady formative years.

We had gravitated towards one another at primary school when we were both about ten and were later accepted into Sydney Girls’ High School. She was everything I was not: blonde, tanned, pretty and popular with all the boys. She had an older brother and could relate to the opposite sex whereas, coming from an all-girl family, I found them totally alien. We first caught the 380 bus down to that iconic crescent beach in 1976. The smell of tropical suntan oil and the spray off the waves was intoxicating. Girls lay sprawled topless on their towels, their erect nipples courting the gaze of passers-by, their bronzed legs bent just so … to reveal their inner thigh. And then there were the boys: the pecs, the tight bums, the stringy blond hair, the sight of them all glistening wet in the sunlight as they stripped out of their wetsuits to reveal their scungies. The term ‘budgie smuggler’ has since come into popular use to describe this vision but back then words simply weren’t enough. The sight was captivating and my eyes gobbled it up in a manner not dissimilar to artist Tracey Moffatt in her ironic perv fest video Heaven which could well have been based on this excerpt from Lette and Carey’s book:

The art of changing in and out of boardshorts at the beach was always done behind a towel … The ultimate disgrace for a surfie was to be seen in his scungies. They were too much like underpants. The boys didn’t want us checking out the size of their dicks.4

On the very first page of Puberty Blues, we are introduced to the hierarchy of the beach. Debbie and Sue start out as ‘dickheads’ occupying the lowly area of South Cronulla Beach along with the migrant family groups and kids from the western suburbs known as ‘Bankies’—short for Bankstown—where many of them lived. Em and I weren’t exactly dickheads, or ‘westies’ as we called them, but we weren’t in the top gang either when we first made our moves on Bondi. There was, however, a similar delineation of zones. The coolest of the cool hung out on the hill above South Bondi with the best view of the waves. There was another gang, the Rock Crew, who oiled their bulging biceps around an exposed rock just down from the southern-most ramp off the promenade. These guys surfed a bit but mostly they were interested in modelling menswear and plucking the spunkiest chicky babes off the sand. Way down at the northern end of the beach was Dagsville—no one ever surfed there unless the swell was really pumping. To begin with, we were on the periphery of the gangs at the south end. Our little group hung around the third ramp behaving badly. I’ve got a photo of one of the boys chucking a browneye for the camera in full daylight: so very mature. All summer long we had fun, tanning and swimming and watching the boys surf. Just like the girls in the book.

When winter arrived it was as if nature suddenly threw a big soggy dampener on the whole beach party. Em and I, however, were not about to be shut out of the fun that easily. We were thirteen and raring to go so we got ourselves jobs working as waitresses at the Sunshine Inn at North Bondi serving up Hunza Pie and spiralina shakes and saved up to buy ourselves surfboards. Ten dollars bought me a beaten-up six-foot Graham King, Em got herself an eight-inch-longer McCoy and in May 1977 we took the plunge, crossing over that gender divide between the sand and the surf. There were perhaps only a couple of other female surfers braving the waves back in those days so we definitely stood out. At first we could hardly balance on the boards and were ridiculed mercilessly by the guys. But soon we were hooked, if not obsessed, and would go out in the most gnarly conditions like dedicated kamikazes. The boys finally caught on that we were ‘dead set’ and stopped bagging us. We’d get up at 3 a.m. in the pitch dark before the buses were running and walk the five or so kilometres to Bondi to catch ‘the early’. Nothing was so liberating as being out there in the dark water overcoming our fear of sharks and watching the sky slowly change from black to blue to pink to yellow to red. We were morphing into soul surfers and before too long we’d managed to slide up the hill to hang with the other cool grommets.

The next year, after just ten months of dedicated wave action, we were featured in the surfing magazine Sea Notes.5 There were two big photos with a caption that proved prophetic, at least for me: ‘We’re going to be actresses’. There was also a quote from Em, which read, ‘On Thursdays we can surf through first period. It’s only scripture’. The interview, we announced, was setting us back about two hours of beauty treatment time but surfing was something that needed promoting: ‘It’s so gas. It’s just really free’, I said. The only trouble was the outfit: ‘It’s a bit of a hassle in bikinis because they slip everywhere and you’ve tits flying everywhere … you get stared at too’. Asked if there was anyone that we wanted to surf like, I named one of the most radical surfers of the day: ‘Gerry Lopez. No women idols because you never see any. I’ve never seen any film clips of women surfers … these chauvinistic films I dunno’. We had seen films like Hot Lips and Inner Tubes and Tubular Swells but no women featured in them. We were carving out our own patch of urban ocean and before long I was Treasurer for the New South Wales Women’s Surfing Association. I even entered the Pepsi Golden Breed Pro Junior surfing tournament and was interviewed on 2JJ—as ABC’s youth radio station was then called. But surfing was not without its hazards and I was the victim of a fin chop which required eleven stitches, five of which I still have in a scrapbook.

That year, aged fourteen, I fell in love with a macrobiotic poet surfer called Daz. It was deep. We ordered brand new matching surfboards and hitchhiked up the New South Wales coast to camp and surf at all the legendary spots: Crescent Head, Angourie, Byron Bay. Our soundtrack that summer was from Albie Falzon’s seminal surfing film Morning of the Earth. Songs like ‘Simple Ben’ and ‘Open Up Your Heart’ went round and round the cassette player ’til they almost erased themselves. Every other soul surfer worth their board wax was tuning in to the same magical music, making it the first locally-made film soundtrack to go triple gold.6 Daz, three years older than I, was reading Patrick White’s The Tree of Man for his school exams while I was reading Spiritual Midwifery in preparation for my role as Earth Mother. My father took decisive action and on my fifteenth birthday moved me to an all-girl private school where the uniforms were a suitably boy-repellent shade of olive green.

I was like a freak of nature, dumped in the middle of this posh scenario with my three massive diamante studs in one earlobe, not to mention the weirdo hairdos I’d been fostering at Sydney High (hairdos that were eventually to find their way onto Debbie Vickers’ head ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Author’s Biography

- Australian Screen Classics

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- Puberty Blues

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Filmography

- Credits

- Copyright Details

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Puberty Blues by Nell Schofield in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Radio. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.