![]()

1

The sea, the sea

Jane Campion once spoke of a movie, Ebb, which she considered, but never made:

It was an imaginary story about a country where one day the sea leaves, never returns, and the way in which the people have to find a spiritual solution to this problem. The natural world had become artificial and unpredictable and the film spoke about faith and doubt. The inhabitants of this country had developed a certain form of spirituality, hearing voices, having visions.1

There is something strangely compelling in this mini-narrative, and in oblique ways it speaks of the concerns of The Piano. A movie premised, hypothetically at least, on loss and redemption, on a spiritual struggle to deal with the bewildering subtraction of something that had seemed otherwise essential, The Piano, also, attempts to ‘solve’ certain conditions of absence and estrangement, the world made unfamiliar, the challenge of recovery, of forms of damage that can only be negotiated by visions. Curiously, too, The Piano works with a sensibility of immersion, as if in a dialectical gesture willing the flow that Ebb hypothetically cancelled. According to cinematographer, Stuart Dryburgh,

Part of the director’s brief was that we would echo the film’s element of underwater in the bush. ‘Bottom of the fish tank’ was the description we used for ourselves to define what we were looking for. So we played it murky green-blue.2

What symbolic sea-space is this? Why the wish for a fish-tank filter of murky aquamarine? And what directorial command, therefore, to obliterate visually, if only in certain scenes or as a suggestive and subliminal trace, the necessary division of earth and ocean? The nineteenth-century critic John Ruskin once famously described the sea as ‘an irreconcilable mixture of fury and formalism’, expressing exasperation at its representational challenge. What is worth exploring, I think, are the ways in which The Piano is hinged on just this kind of contradiction: an aesthetic of both containment and excess, the rhythmical unrolling of images, recurring with wave-like regularity, but also their overlapping, an interior turbulence, a sense of spill into dimensions of sublimity and vastness. Every movie, of course, is a motion picture, a system of fluctuation and ‘continuous mobility’.3 What is interesting here is the wave-motion of certain movies, the forms in which they rehearse the making and unmaking within the frame, their spatial and temporal logic, their manufacture of cinematic coherence, their roiling to the shore of a more-or-less specific conclusion.4

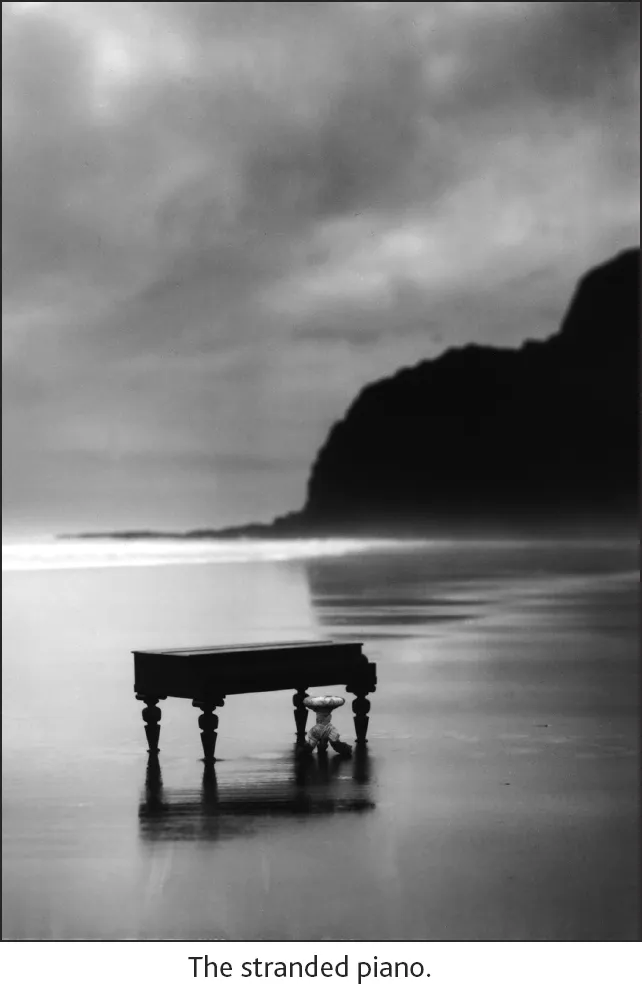

Revising Ebb, the look of The Piano is thus often submarine: there is a watery quality to many of the shots, and New Zealand, the principal setting, is remade as a perilous and drenching heterotopia, a place not for touristic or colonial satisfactions of the picturesque, but somewhere other-worldly, deep, bluish, strange, somewhere, indeed, that might ultimately suck one under, or dissolve the self into place in disturbing ways.5 Described by one writer as ‘a muddy, glutinous (and) fluid landscape’, it might also therefore be read as feminised.6 The sea is recurrently evoked, prayed to in a Maori ritual, photographed as bands of light and dark, or thundering dramatically at the limits of the visible world.

Add to this Michael Nyman’s famously hypnotic score, which swells and rises, ebbs and flows, saturates the crucial scenes in an irresistible tonal wash. The soundtrack, that is to say, is also fluid; its motifs recur in a kind of compulsive repetition, based in part on the composer’s knowledge of the forms of baroque rounds and canons. The music crests and falls and superimposes; it moves with broad tidal sweep, just as waves do. The climax of the narrative, such as it is, is the heroine’s near-drowning. She descends to expressionist film-making, lapis light and a lush enveloping score, seeming to go down and down, way into shadowy depths, so that her ascent and recovery seem almost a continuity mistake. (More of that later.) And the movie ends, as viewers may puzzle-headedly recall, with an image of the heroine, Ada, suspended beneath the ocean, swaying, darkly obscure, within light-shot currents. Her dress oddly resembles a domed sea creature, ballooning around her. She is filmed from below, as if the camera has finally sunk to the ocean floor, as if that is where the directorial and cinematic consciousness of The Piano finally comes to rest. It is drowned, but seeing. There is then a cut-to-black, and a quote from Silence, a poem by the English poet Thomas Hood (1799–1845), one which initially was to have been used in Ebb.7

There is a silence where hath been no sound,

There is a silence where no sound may be,

In the cold grave—under the deep, deep sea.

In one of the boldest conceptual moves in The Piano, the deep, deep sea that is the destination of this movie is paradoxically both the emblem of the persistence of desire (life) and the loss of desire (death). The voice-over speaks both alive and posthumously, claiming the territory Roland Barthes once identified as the impossible space of pure fiction, the ‘scandal’ of enunciation where none should truly exist.8 The sense of oceanic conclusion, of altered perception, of the beautiful and terrifying reversibility of things, are all contained in the last image and the ripple-lines of quotation that follow it.

So how do we arrive at such a moment of spooky audacity? At such a haunting, deliquescent, point of view? How has this second Ebb, or this putative Flow, returned the ocean in a post-colonial narrative? And what does it mean to align passion with natural forces, to situate subjects in the drag and undertow of altered states and rhythms? In this essay I wish to address the physical quirkiness of The Piano (its representations of the body and sense experience), and to investigate its peculiar, and peculiarly insistent, metaphysics. This is a movie much written about—sometimes in depressingly reductive and schematic ways—yet it carries an aesthetically distinctive poetics, even as it rehearses familiar genres with mostly familiar movie stars. Famously, too, The Piano inspires adoration, sometimes to the point of gushy devotion, so I wish also to examine its remarkable emotional appeal. Its popular success—as the winner of three Academy Awards in 1994 and the prestigious Palme d’Or at Cannes in 1993 (shared with Chen Kaige’s Farewell My Concubine)—has in many ways occluded the formal qualities of the movie, and presented it, predictably, in more market-driven terms: the virtuosity of the stars, the sexual plot, the dank exoticism of darkest New Zealand. Early reviewers sometimes offered appalled condemnation: Stanley Kauffmann calls it ‘an over-wrought, hollowly symbolic glob of glutinous nonsense’ and says:

‘[I] haven’t seen a sillier film about a woman and her piano since John Huston’s The Unforgiven (1960) in which Lillian Gish had her piano carried out into the front yard so she could play Mozart to pacify attacking Indians.’9

More often, however, the reception was one of extraordinary praise, often couched in highly emotive terms: ‘For a while I could not think, let alone write about The Piano without shaking. Precipitating a flood of feelings, The Piano demands as much a physical and emotional response as an intellectual one … I wanted to rush at the screen and shout and scream.’10 Such strong identifications and fervent responses have formed the basis of both feminist and anti-feminist criticism and been the reason for the film’s acceptance or rejection. Acknowledging its emotional appeal, another critic writes: ‘The film gives reason nothing to do.’11 So in this essay I shall impersonate the visitor from the land of Ebb, who sees the movie for the very first time. I shall assess its unearthly and controversial visions, its attractive powers, and its capacity to alienate and to entrance.

![]()

2

Too strangely near: the romantic plot

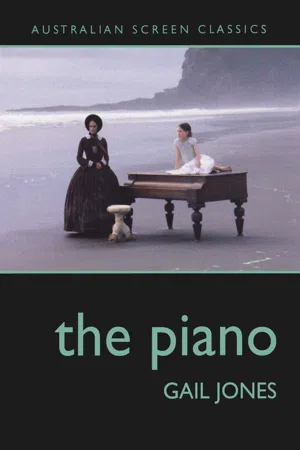

The story is well known. Our heroine, Ada McGrath (Holly Hunter), a mute Scottish woman, is sent by her father to marry a man, Alisdair Stewart (Sam Neill), in colonial New Zealand. It is perhaps 1860, judging by the costumes. She has a young daughter, Flora (Anna Paquin), and there is some unexplained, possible shameful, history she carries. Certainly it seems likely that Flora is ‘illegitimate’, so that the marriage is marked at the outset as opportunistic, as one of ‘convenience’. Apart from her silent condition, Ada is unusual in that she exhibits a fierce ardour for, and even identification with, her Broadwood piano, the prosthetic object, as it were, for her missing voice.12 Mother, daughter and piano are all shipped to the colony to be collected by Stewart, and inserted into the second neat triangle of a ready-made family. Instead, however, the domestic plot is overturned when Stewart trades his new wife’s piano to George Baines (Harvey Keitel), a colonist with Maori sympathies. Ada is seduced (or perhaps self-traded) into a relationship with Baines, a curiously passive, quiet and indecisive figure, in order to recover possession of the piano. The interior action takes place between Stewart’s house, Baines’s house, and ‘the mission house’, a place where the Reverend (Ian Mune), Aunt Morag (Kerry Walker) and Nessie (Genevieve Lemon)—all of whom bear an unclear relation to Stewart—uphold standards of strict Scottish rectitude by which the illicit lovers will be judged. A further triangle develops, the third term of which once again is Flora. Her presence is perhaps the most volatile in the movie: she has voice, energy and wilfully mischievous agency. She shouts, runs, performs, betrays and displays a ventriloquising relationship with her mother that curiously joins and ‘weds’ them. In the collision of passions that follows, Stewart attacks Ada, severing one of her fingers with an axe, and then confronts Baines, threatening but releasing him. The resolution is fractured and complicated—of which more later—but Baines, Ada and Flora create an entirely new family, settled together in the South Island township of Nelson. It is a story resolved romantically, but also with a certain complicating and confusing mysticism.

Initially called ‘The Piano Lesson’, then ‘The Sleep of Reason’, earlier versions of the script were more violent and tempestuous. There were more fingers hacked off, and Baines kills Stewart. The script, that is to say, moved away from exaggerated and dramatic violence, towards threat, to interiority and psychological drama, and to all that resides in the allusion to Goya’s famous etching, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters: irrational release, the night-time other-side of dream, sexual excess and unhinging madness. (Goya’s etching is presumed to be a self-portrait. It depicts a man collapsed asleep at his writing desk—not in bed—with ominous big-eyed, owl-like creatures winging around him. This image invokes the interpenetration of dreaming and writing and the cruel capacity of visions to torment and to arrive unbidden.)

In interviews, Campion has frequently been asked about the sources and inspiration for The Piano, and her responses are remarkably uniform. Significantly, she cites not cinematic precedents, but nineteenth-century literary romance melodramas. Wuthering Heights appears to be an especial favourite, along with novels by Henry James and George Eliot, texts like Kate Chopin’s The Awakening and the poetry of Emily Dickinson. The novel version of The Piano (co-written by Jane Campion and Kate Pullinger in 1994) is prefaced with the following quote:

Today I will seek not the shadowy region;

Its unsustaining vastness waxes drear;

And visions rising, legion after legion,

Bring the unreal world too strangely near.

Taken from Emily Bronte’s Stanza (1846), this may be read as the director’s own literary-critical gloss on her work: it expresses both an attraction to the visionary and a reluctance wholly to entertain it; the shadowy region hovers as a possibly pathological enticement to Victorian women bent on artistic or emotional escapism. The mode of Gothicism may be implicitly cinematic: with its imagistic repertoire of wild spaces, supernatural occurrences, extravagant announcements and scenes of out-of-control passion on dark-and-stormy nights. The high romanticism of the Gothic, too, often construed in sexualised encounters, fits well with the emotional and fantasy regimes of cinema. In an interesting argument, the f...