LIFE AND CAREER

Born in 1863, Stanislavsky saw profound scientific and social changes take place as the nineteenth century became the twentieth. Living in Russia, he experienced artistic traditions from both Europe and Asia. Before his death in 1938, he witnessed three great revolutions: realism’s overturn of nineteenth-century histrionics, modernism’s rejection of realism, and Russia’s political move from monarchy to communism. The first two shaped his career and made him world famous; the last turned him from a wealthy man into a poor one, from an artist who shaped modern theatre into one who was shaped by political forces. ‘In truth, many changes occurred during my life’, he wrote, ‘and more than once were they fundamental’ (Stanislavskii 1988b: 3).

Born Konstantin Sergeevich Alekseev into one of Russia’s wealthiest manufacturing families, he lived a privileged youth. He regularly visited plays, circuses, ballets and the opera. He expressed adolescent theatrical impulses in a fully equipped theatre, built by his father in 1877 at the family estate, and as he grew, he often used his wealth to further his talents as actor and director. Until the communist revolution, he personally financed many of his most productive artistic experiments: in 1888 he founded the critically acclaimed theatrical enterprise the Society of Art and Literature; in 1912 he started the First Studio to develop his System for actor training.

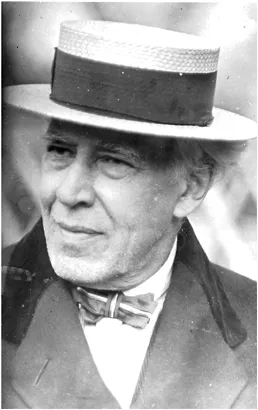

Until the age of thirty-three, Stanislavsky performed and directed only as an amateur. In early nineteenth-century Russia, many actors had been serfs, appearing at the behest of their owners; even after the abolition of serfdom, actors continued to be regarded as lower-class citizens. Hence, whilst the Alekseev family loved theatre, they discouraged their children from professional aspirations which threatened social embarrassment. The critics, too, respected decorum when they tactfully praised an anonymous ‘K. A–v’ for outstanding performances in productions by the Society of Art and Literature. In 1884, Konstantin Alekseev began to act without his family’s knowledge, under the stage name Stanislavsky.1

With the founding of the Moscow Art Theatre in 1897, Stanislavsky turned professional. The playwright and theatre educator Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko had chosen the impressive amateur as his co-director in an idealistic effort ‘to reconstruct [theatre’s] plays’ (Nemirovitch-Dantchenko [sic] 1937: 68). Their first meeting at a Moscow restaurant lasted a legendary eighteen hours. Their conversation set in motion the company that would bring the latest European ideas in stage realism to Russia, and new standards in acting to the world.

In order to understand the revolutionary impact of their endeavour one need only compare the 1896 production of Chekhov’s The Seagull at the Imperial Aleksandrinsky Theatre with the Moscow Art Theatre’s staging two years later. The first relied on nineteenth-century conventions. It served as a benefit for a popular comic actress and featured a star. The cast met for a few rehearsals, learning their parts on their own and supplying their own costumes. The theatre used sets from the existing stock. Despite its mythic failure on opening night, The Seagull attained, in Danchenko’s

words, ‘routine’ success (Nemirovitch-Dantchenko [sic] 1937: 63). By this, he meant that the Aleksandrinsky production entertained its audiences in typically nineteenth-century fashion, without any concessions in staging or acting to Chekhov’s twentieth-century innovations in drama. In contrast, the Moscow Art Theatre put eighty hours of work into thirty-three rehearsals in order to cultivate an ensemble of actors without stars. Sets, costumes, properties and sound (including humming crickets and barking dogs) were all carefully designed to support a unified vision of the play. The directors held three dress rehearsals. Even so, Stanislavsky considered the 1898 Seagull under-rehearsed (Benedetti 1990: 82).

With this production, Stanislavsky became known as Chekhov’s definitive director, and the Moscow Art Theatre took its place in the history of twentieth-century theatre.2 Moreover, from this point forward, Stanislavsky’s name and that of the Art Theatre became inextricably linked. His work on Chekhov’s major plays (1898– 1904), Gorky’s The Lower Depths (1902), Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People (1900), and his playing of such roles as the fussy old Famusov in Griboedov’s Woe From Wit (1906) created his reputation as a leading realistic director and a gifted character actor.

No sooner had the Moscow Art Theatre established itself as the leader in realism, than symbolist playwrights and theatricalist directors revolted against representational theatre. Symbolists wanted to get beyond the illusions of reality by creating poetic expressions of the transcendental and spiritual. Theatricalists enjoyed making spectators aware of the conventions of performance, sets and costumes, much as abstract artists bring viewers’ attention to canvas and paint. Both groups fostered non-realistic theatrical forms. Whilst Stanislavsky tackled the new styles with productions of symbolist plays in 1907 and 1908,3 these efforts left little imprint on the character of the Art Theatre, which remained a bastion of realism.

Stanislavsky, however, wished to explore more widely. At various times during his career he experimented with symbolism, verse, opera, Western psychology, Yoga and Eastern ideas on the mind/body continuum, modern dance, and trends in criticism of art and literature. In short, he willingly embraced anything that could illuminate acting and drama. Paradoxically, whilst the Moscow Art Theatre fostered his fame as a master of psychological realism, it also clipped his wings in other directions. Whilst the actors saw his experimentation as eccentric, Nemirovich-Danchenko considered ‘Stanislavskyitis’ as dangerous to the stability of their theatre (2005: 294). As a sharp businessman, Danchenko insisted that they continue to build upon their initial success with realistic styles. As a consequence, Stanislavsky moved his experiments to a series of studios, adjunct to the main stage and independently financed.

Take the System as a case in point. Stanislavsky became the first practitioner in the twentieth century to articulate systematic actor training, but he did so largely outside the confines of the Moscow Art Theatre. He began to develop what he called a ‘grammar’ of acting in 1906, when his performances as Dr Stockmann (An Enemy of the People) had begun to falter. He brought his new ideas and techniques to his home company in 1909 whilst rehearsing Turgenev’s A Month in the Country. Although he had banned Danchenko from attending these rehearsals so as to alleviate tension, he still met with resistance from the actors, who had succeeded in Chekhov’s plays without any ‘eccentric’ exercises. In 1911, a frustrated Stanislavsky threatened to resign if the company did not adopt his System as its official working method. Danchenko relented, but reluctantly. After one year, the seasoned actors still remained sceptical and Stanislavsky finally stepped outside of the Art Theatre and created the First Studio in order to work with more willing actors.

The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 left Russia in chaos. Civil war raged until 1921, food and necessities became scarce and inflation made the rouble all but worthless. In the upheaval, Stanislavsky lost the wealth and privileges of his youth. The Soviets confiscated his family home and factory. He began to sell his remaining possessions to survive. ‘My life has completely changed’, he wrote. ‘I have become proletarian’ (Stanislavskii 1999: 18). When his son fell ill with tuberculosis, he could not afford treatment (Stanislavskii 1999: 110). Facing eviction in 1920, Stanislavsky turned for help to Lenin’s newly appointed Commissar of Enlightenment, Anatoly Lunacharsky, who was himself a playwright. Lunacharsky pleaded with Lenin on Stanislavsky’s behalf, stressing that he was ‘about to see his last pair of trousers’ (Hecht 1989: 2). The state relented by allocating Stanislavsky a modest house with two rooms for rehearsals.4

The Moscow Art Theatre also struggled in post-revolutionary Russia. At the time of the Revolution, the theatre required 1.5 billion roubles to operate, whilst its box office receipts totalled only 600 million (Benedetti 1990: 250). Without more profit or governmental subsidy the theatre could not survive. Both sources of income proved impossible in the wake of the Revolution. The theatre mounted only one new production between 1917 and 1922 – Byron’s Cain. Its set could not be built as designed, due to the lack of funds. Therefore, Stanislavsky decided to use a simple black backdrop for the production. Even so, enough velvet to enclose the full stage could not be found (Benedetti 1990: 244).

Stanislavsky and the Moscow Art Theatre looked to the West, and more specifically to America, for financial survival. As Stanislavsky soberly wrote to Danchenko in 1924: ‘America is the sole audience, the sole source of money for subsidy, on which we can count’ (Stanislavskii 1999: 138). Thus, the company split into two. Stanislavsky led the most famous actors on tour throughout Europe and the United States; Danchenko kept the theatre open in Moscow. The tours lasted two years (1922–24) and were unabashedly intended to make money for the floundering theatre. Only fame, however, resulted.

Many of the Moscow Art Theatre’s talented actors traded their fame for employment in the West as actors, directors and teachers, rather t...