- 316 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Building on the strengths of the first edition, this accessible and user-friendly textbook explores the strategies of comparative research in political science. It begins by examining different methods, then highlights some of the big issues in comparative politics using a wealth of topical examples before discussing the new challenges in the area. Thoroughly revised throughout with the addition of extensive new material, this edition is also supplemented by the availability online of the author's datasets.

The book is designed to make a complex subject easier and more accessible for students, and contains:

* briefing boxes explaining key concepts and ideas

* suggestions for further reading at the end of each chapter

* a glossary of terms.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Issues and Methods in Comparative Politics by Todd Landman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Political Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

PhilosophySubtopic

Political PhilosophyPart I

WHY, HOW, AND

PROBLEMS OF

COMPARISON

PROBLEMS OF

COMPARISON

1 | Why compare countries? |

2 | How to compare countries |

3 | Choosing countries and problems of comparison |

The chapters in this part of the book establish the rationale for the systematic comparison of countries, demonstrate the different ways in which countries can be compared, and examine the various problems that scholars have confronted or will confront when comparing countries. Too often, both the choice of countries and the way in which they are compared are decided for reasons not related to the research question. In contrast, these chapters argue that the comparative research strategy matters. From the initial specification of the research problem, through the choice of countries and method of analysis, to the final conclusions, scholars must be attentive to the research question that is being addressed and the ways in which the comparison of countries will help provide answers.

To this end, Chapter 1 shows that the comparison of countries is useful for pure description, making classifications, hypothesis-testing, and prediction. It then shows how methods of comparison can add scientific rigour to the study of politics in helping students and scholars alike make stronger inferences about the political world they observe. This is followed by a discussion of key terms needed for a science of politics including theory and method; ontology, epistemology, and methodology; cases, units of analysis, variables, and observations; levels of analysis; and quantitative and qualitative methods. Chapter 2 delves deeper into the different ways in which countries can be compared and why these different methods matter for making inferences. It argues that scholars face a key trade-off between the level of conceptual abstraction and the scope of countries under study. It shows how comparing many countries, few countries, or single-country studies all fit under the broad umbrella of ‘comparative politics’, and that all have different strengths and weaknesses for the ways in which political scientists study the world.

Finally, Chapter 3 outlines the main problems that confront comparativists and suggests ways in which to overcome them. These problems include ‘too many variables and too few countries’, establishing equivalence between and among comparative concepts, selection bias, spuriousness, ecological and individualist fallacies, and value bias. Together, these chapters offer a synthesis of comparative methods and provide a ‘toolchest’ for students and scholars that can be used to approach both existing and new research questions in political science.

Chapter 1

Why compare

countries?

countries?

Reasons for comparison

The science in political science

Scientific terms and concepts

Summary

Further reading

Making comparisons is a natural human activity. From antiquity to the present, generations of humans have sought to understand and explain the similarities and differences they perceive between themselves and others. Though historically, the discovery of new peoples was often the product of a desire to conquer them, the need to understand the similarities and differences between the conquerors and the conquered was none the less strong. At the turn of the new millennium, citizens in all countries compare their position in society to those of others in terms of their regional, ethnic, linguistic, religious, familial, and cultural allegiances and identities; material possessions; economic, social and political positions; and relative location in systems of power and authority. Students grow up worried about their types of fashion, circle of friends, collections of music, appearance and behaviour of their partners, money earned by their parents, universities they attend, and careers they may achieve.

In short, to compare is to be human. But beyond these everyday comparisons, how is the process of comparison scientific? And how does the comparison of countries help us understand the larger political world? In order to answer these important questions, this chapter is divided into four sections. The first section establishes the four main reasons for comparison, including contextual description, classification and ‘typologizing’, hypothesis-testing and theory-building, and prediction (Hague et al. 1992: 24–27; Mackie and Marsh 1995: 173–176). The second section specifies how political science and the sub-field of comparative politics can be scientific, outlining briefly the similarities and differences between political science and natural science. The third section clarifies the terms and concepts used in the preceding discussion and specifies further those terms and concepts needed for a science of politics. The fourth section summarizes these reasons, justifications, and terms for a science of comparative politics.

Reasons for comparison

Today, the activity of comparing countries centres on four main objectives, all of which co-exist and are mutually reinforcing in any systematic comparative study, but some of which receive more emphasis, depending on the aspirations of the scholar. Contextual description allows political scientists to know what other countries are like. Classification makes the world of politics less complex, effectively providing the researcher with ‘data containers’ into which empirical evidence is organized (Sartori 1970: 1039). The hypothesis-testing function of comparison allows the elimination of rival explanations about particular events, actors, structures, etc. in an effort to help build more general theories. Finally, comparison of countries and the generalizations that result from comparison allow prediction about the likely outcomes in other countries not included in the original comparison, or outcomes in the future given the presence of certain antecedent factors.

Contextual description

This first objective of comparative politics is the process of describing the political phenomena and events of a particular country, or group of countries. Traditionally, in political science, this objective of comparative politics was realized in countries that were different to those of the researcher. Through often highly detailed description, scholars sought to escape their own ethnocentrism by studying those countries and cultures foreign to them (Dogan and Pelassy 1990: 5–13). The comparison to the researcher’s own country is either implicit or explicit, and the goal of contextual description is either more knowledge about the nation studied, more knowledge about one’s own political system, or both. The comparative literature is replete with examples of this kind of research, and it is often cited to represent ‘old’ comparative politics as opposed to the ‘new’ comparative politics, which has aspirations beyond mere description (Mayer 1989; Apter 1996). But the debate about what constitutes old and new comparison often misses the important point that all systematic research begins with good description. Thus description serves as an important component to the research process and ought to precede the other three objectives of comparison. Purely descriptive studies serve as the raw data for those comparative studies that aspire to higher levels of explanation.

From the field of Latin American politics, Macauley’s (1967) Sandino Affair is a fine example of contextual description. The book is an exhaustive account of Agusto Sandino’s guerrilla campaign to oust US marines from Nicaragua after a presidential succession crisis. It details the specific events surrounding the succession crisis, the role of US intervention, the way in which Sandino upheld his principles of non-intervention through guerrilla attacks on US marines, and the eventual death of Sandino at the hands of Anastasio Somoza. The study serves as an example of what Almond (1996: 52) calls ‘evidence without inference’, where the author tells the story of this remarkable political leader, but the story is not meant to make any larger statements about the struggle against imperialism. Rather, the focus is on the specific events that unfolded in Nicaragua, and the important roles played by the various characters in the historical events.

Classification

In the search for cognitive simplification, comparativists often establish different conceptual classifications in order to group vast numbers of countries, political systems, events, etc. into distinct categories with identifiable and shared characteristics. Classification can be a simple dichotomy such as between authoritarianism and democracy, or it can be a more complex ‘typology’ of regimes and governmental systems. Like contextual description, classification is a necessary component of systematic comparison, but in many ways it represents a higher level of comparison since it seeks to group many separate descriptive entities into simpler categories. It reduces the complexity of the world by seeking out those qualities that countries share and those that they do not share.

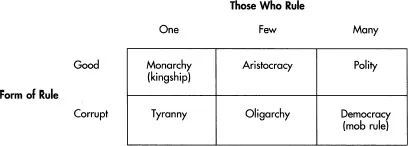

The process of classification is not new. The most famous effort at classification is found in Aristotle’s Politics (Book 3, Chapters 6–7), in which he establishes six types of rule. Based on the combination of their form of rule (good or corrupt) and the number of those who rule (one, few, or many), Aristotle derived the following six forms: monarchy, aristocracy, polity, tyranny, oligarchy, and democracy (see Hague et al. 1992: 26). A more recent attempt at classification is found in Finer’s (1997) The History of Government, which claims that since antiquity (ca. 3200 BC), all forms of government have belonged to one of the following four basic types: the palace polity, the church polity, the nobility polity, and the forum polity. Each type is ‘differentiated by the nature of the ruling personnel’ (ibid.: 37). In the palace polity, ‘decision-making rests with one individual’ (ibid.: 38). In the church polity, the church has a significant if not exclusive say in decision-making (ibid.: 50). In the nobility polity, a certain pre-eminent sector of society has substantial influence on decision-making (ibid.: 47). In the forum polity, the authority is ‘conferred on the rulers from below’ by a ‘plural headed’ forum (ibid.: 51). Aristotle’s classification was derived deductively and then ‘matched’ to actual city states, while Finer’s classification scheme is based on empirical observation and inductive reasoning (see below for the distinction between these two types of reasoning). Both scholars, however, seek to describe and simplify a more complex reality by identifying key features common to each type (see Briefing Box 1.1).

Hypothesis-testing

Despite the differences between contextual description and classification, both forms of activity contribute to the next objective of comparison, hypothesis-testing. In other words, once things have been described and classified, the comparativist can then move on to search for those factors that may help explain what has been described and classified. Since the 1950s, political scientists have increasingly sought to use comparative methods to help build more complete theories of politics. Comparison of countries allows rival explanations to be ruled out and hypotheses derived from certain theoretical perspectives to be tested. Scholars using this mode of analysis, which is often seen as the raison d’être of the ‘new’ comparative politics (Mayer 1989), identify important variables, posit relationships to exist between them, and illustrate these relationships comparatively in an effort to generate and build comprehensive theories.

Arend Lijphart (1975) claims that comparison allows ‘testing hypothesized empirical relationships among variables’. Similarly, Peter Katzenstein argues that ‘comparative research is a focus on analytical relationships among variables validated by social science, a focus that is modified by differences in the context in which we observe and measure those variables’ (in Kohli et al. 1995:11). Finally, Mayer (1989: 46) argues somewhat more forcefully that ‘the unique potential of comparative analysis lies in the cumulative and incremental addition of system-level attributes to existing explanatory theory, thereby making such theory progressively more complete’. The symposia on comparative politics in World Politics (Kohli et al. 1995) and the American Political Science Review (vol. 89, no. 2, pp. 454–481), suggest that questions of theory, explanation, and the role of comparison are at the forefront of scholars’ minds.

Briefing box 1.1 Making classifications: Aristotle and Finer

Description and classification are the building blocks of comparative politics. Classification simplifies descriptions of the important objects of comparative inquiry. Good classification should have well-defined categories into which empirical evidence can be organized. Categories that make up a classification scheme can be derived inductively from careful consideration of available evidence or through a process of deduction in which ‘ideal’ types are generated. This briefing box contains the oldest example of regime classification and one of the most recent. Both Aristotle and Samuel Finer seek to establish simple classificatory schemes into which real societies can be placed. While Aristotle’s scheme is founded on normative grounds, Finer’s scheme is derived empirically.

Constitutions and their classifications

In Book 3 of Politics, Aristotle derives regime types which are divided on the one hand between those that are ‘good’ and those that are ‘corrupt’, and on the other, between the different number of rulers that make up the decision-making authority, namely, the one, the few, and the many. Good government rules in the common interest while corrupt government rules in the interests of those who comprise the dominant authority. The intersection between these two divisions yields six regime types; all of which appear in Figure 1.1. The figure shows that the good types include monarchy, aristocracy, and polity. The corrupt types include tyranny, oligarchy, and democracy. Each type is based on a different idea of justice (McClelland 1997: 57). Thus, monarchy is rule by the one for the common interest, while tyranny is rule by the one for the one. Aristocracy is rule by the few for the common interest, while oligarchy is rule by the few for the few. Polity is rule by the many for the common good, while democracy is rule by the many for the many, or what Aristotle called ‘mob rule’.

Figure 1.1 Aristotle’s classification scheme

Sources: Adapted from Aristotle (1958: 110–115); Hague et al. (1992: 26); McClelland (1997:57)

Types of regime

Finer (1997: 37) adopts an Aristotelian approach to regime classification by identifying four ‘pure’ types of regime and their logical ‘hybrids’. Each regime type is based on the nature of its ruling personnel. The pure types include the palace, the forum, the nobility, and the church. The hybrid types are the six possible combinations of the pure types, palace–forum, palace–nobility, palace–church, forum–nobility, forum–church, and nobility–church. These pure and hybrid types are meant to describe all the regime types that have existed in world history from 3200 BC to the modern nation state. Finer concedes that there are few instances of pure forms in history and that most politics fit one of his hybrid types. These pure forms, their hybrids, and examples from world history appear in Figure 1.2. The diagonal that results from the intersection of the first row and column in the figure represents the pure forms, while the remaining cells contain the hybrid forms. Many regime types that were originally pure became hybrid at different points in history. Of all the types, the pure palace and its variants have remained the most common through history, and despite its popularity today, the forum polity that represents modern secular de...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- List of Briefing Boxes

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part 1 Why, How, And Problems of comaparison

- Part II Comparing Comparison

- Part III Comparative Methods and New Issues

- Glossary

- References

- Index