![]()

Chapter 1

The Genocide of California’s Yana Indians

Benjamin Madley

On August 28, 1911, a Yahi Yana man emerged from the Sierra Nevada Mountains at a slaughterhouse corral in Oroville, California (Oroville Daily Register, August 29, 1911, p. 1). He was alone, having lost his family and his tribe (Waterman, 1918, p. 64). Scholars studied him intensively and he soon became famous as Ishi, “the last of the Yanas” and “the last wild Indian in North America” (Pope, 1932; Kroeber, 1961). He was, in fact, a genocide survivor. Before 1847 the Yana may have numbered more than 3,000 people;1 by 1872, when Ishi was about 10 years old, perhaps a few dozen survived (Kroeber, 1961, p. 43). Despite an extensive Yana ethnography and many books about Ishi, there exists no comprehensive narrative of this cataclysm.2

In 1918 anthropologist T.T. Waterman outlined the tribe’s demographic decline. Author Theodora Kroeber and others then enhanced his narrative, and in 1987 anthropologist Russell Thornton asserted—in a brief summary of the Yana population decline—that they “were destroyed virtually overnight … in large part because of their genocide by settlers in north-central California during the mid-1850s” (Waterman, 1918; Kroeber, 1961, pp. 56–78; Thornton, 1987, pp. 110, 109–114). Using varied sources—including many new to Yana studies—this chapter builds on previous scholarship and expands upon information provided in American Genocide: The California Indian Catastrophe, 1846–1873 to create the most detailed history yet of the Yana’s near-extermination by individuals, groups, and California state militiamen (Madley, forthcoming).

Why Did the Genocide Happen?

The motives driving immigrants to destroy the Yana changed over time, as did the organization of their killing operations. From 1850 to 1858, immigrants’ violence and destruction of traditional Yana food sources precipitated Yana stock raids to which small, volunteer groups responded with retaliatory massacres. In 1858 immigrants articulated a new goal: removing the Yana by any means necessary, including extermination. State-sanctioned killing and capturing operations—including a state militia operation—unfolded in 1859. Finally, from 1860 to 1871, volunteer death squads hunted surviving Yana in order to punish them for raids, obtain their wealth, and eliminate them as a potential threat. The genocide thus began as disproportionate retaliation, escalated to state-sanctioned mass killing and removal, and concluded with small operations bent on total extermination. All of this violence took place within the context of state and federal decision-makers’ support or acquiescence.

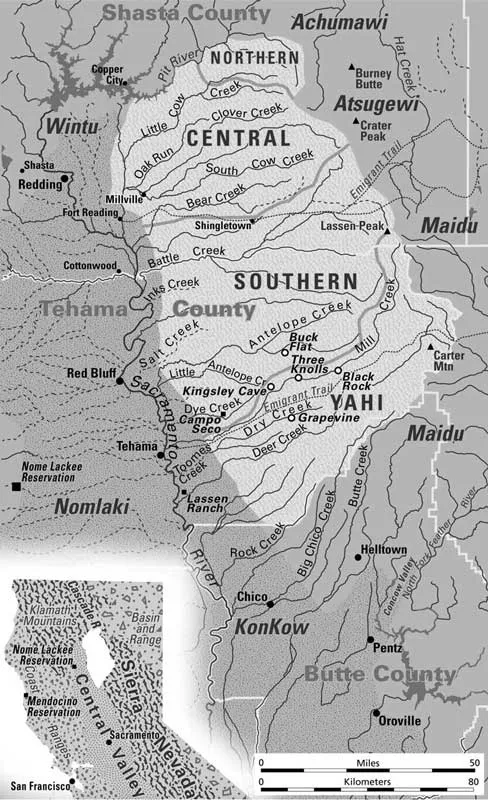

The Yana Before Contact

Before contact with non-Indians, the Yana lived in an ecologically varied, almost Delaware-sized region between the Sacramento River and the southern Cascades of northern California.3 Near the Sacramento, the hills of Yana territory are low, grassy, and oak-studded. Climbing east, canyons deepen and the boulder-strewn land gives way to conifers, alpine meadows, and 10,462-foot-high Lassen Peak. Yana land was rugged but bountiful. Streams supplied salmon and other fish. Oaks yielded acorns. Meadows and grasslands provided grasses and tubers as well as antelope, bear, deer, elk, and small game (Johnson, 1978, p. 361).

They referred to themselves as Yana, meaning “person” (Kroeber, 1925, p. 337; 1961, p. 30). Ethnologists categorized them into four groups, based upon their dialects: Northern Yana, Central Yana, Southern Yana, and the southernmost Yahi Yana, who were Ishi’s people (Kroeber, 1925, p. 338). These groups were linguistically but probably not politically united, as Yana political organization centered around “bands, each of which consisted of a principal village and a number of smaller surrounding settlements” (Waterman, 1918, p. 35; Malinowski, Sheets, Lehman, & Doig, 1998, vol. 4, p. 227).

Yana communities participated in a regional economy. Although sometimes at odds with their California Indian neighbors, they traded with them, often facilitating transactions with dentalia, or seashell currency. “Obsidian was obtained from the Achumawi and Shasta”; “arrows, buckskin, wildcat quivers, and woodpecker scalps were secured from the Atsugewi; clam disc beads and magnesite cylinders, from the Maidu or [Nomlaki] Wintun; dentalium shells, from the Wintu” and “barbed obsidian arrow points, from the north. In return the Yana supplied buckeye fire drills, deer hides, dentalia, salt, and buckskin to the Atsugewi; baskets to the Nomlaki; and salt to the Wintu” (Johnson, 1978, p. 363). Trade connected the Yana to the wider world for centuries, but they were nearly obliterated in 21 years.

Invasion, Raids, and Massacres, 1850–1859

Yana people probably first encountered non-Indians in 1821, but the California Gold Rush transformed their world (Johnson, 1978, p. 362). “By 1848 the California–Oregon trail crossed Northern and Central Yana territory” and from 1848 to 1850 “as many as nine thousand emigrants” traversed the Lassen Cutoff, ripping “a bloody gash through the heart of the Yahi homeland.” Immigrants depleted game and grasses while perhaps engaging in violent conflict (Johnson, 1978, p. 362; Dornin, 1922, pp. 160–164; Stillson, 2006, p. 110; Heizer & Kroeber, 1979, p. 2). As early as 1849 they killed two Yahi Yana people in “Deer Creek cañon” after their camp was robbed (Martin, 1883, p. 80). By 1850, immigrants—some of whom colonized the western edge of Yana territory—were brutalizing and killing Yana people. One of these newcomers was West Point-trained J. Goldsborough Bruff. In the summer of 1850 Bruff reached Lassen’s Ranch and recorded Native Americans—likely Yana given the location—held as forced laborers, tortured, and sometimes killed while their villages were plundered. In a July 11 journal entry, he reported one Indian whipped and another beaten. On August 15, “Battis whipped his squaw in the night.” On November 4,

McBride has very severely whipped a poor indian, and afterwards wounded him with buckshot. I was informed that a year ago, one of Davis’ sons attempted to chastise this very indian, who resisted: and the young man then ordered the indian’s brother to hold him, while he whipped him: this, of course, the Indian refused, when Young Davis shot him dead, on the spot.

Bruff also described the August and September plundering of nearby villages (Bruff, Read, & Gaines, 1949, pp. 365, 382–383, 384, 403, 449). Sexual attacks likely generated further Yana resentment. As Bruff theorized, after recording the August gang rape of a Native American woman, “it is such enormities which often bring about collisions between the whites & Indians” (Bruff et al., 1949, p. 382).

To protect themselves, Yana people had three choices. They could seek protection from the newcomers (by becoming servants, concubines, wives, and laborers), fight them, or retreat into the mountains. All three options were hazardous. Living among immigrants posed numerous dangers because Native Americans had almost no legal rights under California law. Meanwhile, fighting was perilous, given the range and firepower disparity between immigrant rifles and Yana bows and arrows. Thus, most Yana chose the mountains.

Throughout the 1850s, immigrants made mountain life increasingly difficult. Few settled deep in the hills, but gold mining elsewhere, coupled with local ranching and hunting, increased hunger and exposure. Hydraulic mining spilled dirt, debris, and toxic mercury into the Sacramento, killing spawning salmon before they reached Yana territory. Newcomers and their stock further depleted hunting, fishing, and harvesting areas while denying the Yana access to what remained (for more on this process, see Kroeber, 1961, p. 49). Finally, the threat of violence and capture forced many Yana into higher, colder, snowier altitudes where food was scarce and survival difficult.

To eat, and perhaps to retaliate, some Yana began raiding ranchers’ stock and property. Immigrants responded with punitive massacres, beginning in 1850. Theodora Kroeber believed that an April 5, 1850 newspaper report describing the retaliatory killing of 22 or 23 Indians near Deer Creek referred to the Yahi Yana. Yet because the same newspaper described Indian killing on the Deer Creek in Maidu territory one week later, it is not clear that this article referred to Yana people (Kroeber, 1961, p. 58; Sacramento Transcript, April 5, 1850, p. 2; April 12, 1850, p. 2). An attack that undisputedly did target the Yana took place later that year. On December 14, 1850, two of Bruff’s Lassen’s Ranch acquaintances told him that after cattle and oxen went missing from a mountain pasture, they tracked the lost stock up Mill Creek. Coming upon a Yahi Yana hamlet, they killed the inhabitants and burned it to the ground (Bruff et al., 1949, vol. 2, p. 937).

Soon thereafter, California legislators imposed anti-Indian measures that created a framework for Yana killing. In a January 1851 speech, California’s first civilian United States governor, Peter Burnett, helped set the course of the state’s Indian policies by declaring “that a war of extermination will continue to be waged … until the Indian race becomes extinct,” while warning that what he called “the inevitable destiny of the race is beyond the power or wisdom of man to avert” (California, 1851a, p. 15). State legislators then put the power of the purse behind Governor Burnett’s declaration. In 1851 they appropriated $500,000 to pay for past and future Indian-hunting campaigns by volunteer California state militia units (California, 1851b, pp. 520–521). The following year they raised another $600,000 for additional volunteer state militia campaigns (California Legislature, 1852, p. 59). Policy-makers thus communicated their support for Indian-killing both by militiamen as well as individuals and unofficial groups.

In August 1851 local men responded to the killing of “a boy” at “Dye’s rancho” by setting out after local Indians. They soon “charged upon … Indians” located “north of the head of Salt creek, about 30 miles from Dye’s,” in Southern Yana territory, “killed two chiefs and captur[ed] fifty-three men, women and children.” Immigrants now issued their first recorded threat to annihilate local Indian people. The prisoners were to “make a treaty with the whites and live peaceably in the valley [or] be slain” (Letter from Mr. Dye summarized in Sacramento Union, August 16, 1851, p. 2)4

Records for the Yana in the early 1850s are thin, but indicate massacres in 1853, 1854, and 1855. When “Tiger Indians [probably Yahi Yana] stole cattle,” in Butte County in 1853, seven men led by Manoah Pence caught and lynched “Express Bill” before attacking “a camp of about thirty warriors.” According to an 1891 history, “The Indians had nothing but bows and arrows and could do but little damage.” Thus, “Twenty-five redskins were killed” (Anonymous, 1891, pp. 113–114). Locals committed two more recorded massacres the following year. The Shasta Courier reported that on January 17, 1854:

nineteen white men started from Mr. Casey’s on Clover Creek for the purpose of whipping a number of Indians, who, the day previous, had stolen some stock from Hooper’s ranch on Oak Run [in or on the margin of Central Yana territory]. The first rancheria they attacked contained but one Indian man, whom they killed. They next fell upon a rancherie [sic] of the tribe headed by “Whitossa” killing eight men and seriously wounding five others. (Gardiner Brooks in the Shasta Courier, February 25, 1854, p. 2)

In March, after stock were stolen near Tehama, “whites started in pursuit, and … killed twenty-three” Indians (probably Yana) “among the rocks of Dry Creek canyon” (Butte Weekly Record, March 11, 1854, p. 2). Then, in about May 1855, whites assaulted a village “less than half a mile from Cow Creek flouring mills”—that is Harrill’s Mill—“on Suspicion” of harboring an Achumawi leader who they claimed was planning “to burn the mill.” One participant counted 13 dead Indian men on the ground while indicating that others may have died of gunshot wounds or immolation (P.A. Chalfant in The Morning Call, January 4, 1885, p. 1).5

Massacres became more frequent in 1856. On March 8, the Shasta Republican reported that Antelope Creek and Cow Creek [Yanas] stole “seven head of cattle from a ranch near Shingletown.” Whites followed, overtook them, and killed six. Several days later, “about thirty hogs were driven off.” Another massacre followed: “The Indians were soon overtaken [and] all killed on the spot, and the white men then fell upon the rancherias, sacrificing to their vengeance men, women and children! About thirty Indians in all were killed” (Shasta Republican, March 8, 1856, p. 2).

Sometimes the mere possibility of theft precipitated atrocity. On April 19, 1856, the Shasta Republican reported that “During the past week a large number of the Cow Creek Indians went to Harrill’s mill [Millville], on Cow Creek … and insisted on being presented with a sack of flour a-piece.” The Republican suggested that these Central Yanas wanted flour for “one of their most important pow-wows.” More likely, they simply needed food, as acorns, game, fish, tubers, and grasses were diminishing under the triple onslaught of ranching, hunting, and mining, even as immigrants denied them access to what remained. Nevertheless, “the three or four men in charge of the mill” refused to provide any flour, the Yana allegedly made “hostile threats,” and “a fight” broke out. When the smoke cleared “About twenty Indians were killed” and their “[r]ancherias … burned” while two mill workers were injured (Shasta Republican, April 19, 1856, p. 2; T.J. Moorman in Sacramento Daily Union, April 22, 1856, p. 2).

Rumors now spread—which later proved false (Shasta Republican, April 26, 1856, p. 2)—that the Cow Creek Yana “were gathering all the forces they could musteri [muster] with the intention of attacking and burning the mill.” Thus, “about a dozen [Shasta] citizens left town” on April 16, “fully armed, in order to garrison the mill.” Reinforcements swelled their number to 42 and on April 17 they divided “into two parties.” Meanwhile, “On [April] 16th … a company of men from Oak Run killed an Indian and wounded one other.” Then, on April 17 or 18, the Clover Creek “party discovered and attacked a rancheria, killing thirteen Indians,” without suffering a single casualty (Shasta Republican, April 1...