In its preamble to the 1949 Housing Act, Congress declared its goal of “a decent home in a suitable living environment for every American family.” In the more than 60 years since this legislation was passed, the federal government has helped fund the construction and rehabilitation of more than 5 million housing units for low-income households and provided rental vouchers to nearly 2 million additional families. Yet, the nation’s housing problems remain acute. In 2011, 49.8 million households lived in physically deficient housing, spent 30% or more of their income on housing, or were homeless (U.S. Census Bureau 2013; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development 2012). Put differently, about 125 million Americans— around 40% of the nation’s population and far more than double the 48.6 million lacking health insurance in 2011 (Todd & Sommers 2012)—confronted serious housing problems or had no housing at all.1

This book tells the story of how the United States has tried to address the nation’s housing problems. It looks at the primary policies and programs designed to make decent and affordable housing available to Americans of modest means. It examines the strengths and weaknesses of these policies and programs and the challenges that still remain. The book takes a broad view of housing policy, focusing not only on specific housing subsidy programs, such as public housing, but also on the federal income tax code and regulations affecting mortgage lending, land use decisions, real estate transactions, and other activities integral to the housing market. Some of these broader aspects of housing policy provide financial incentives for investments in affordable housing, others attempt to make housing available to low-income and minority households and communities by penalizing discriminatory practices and through other regulatory interventions.

Put simply, then, this book is about policies and programs designed to help low-income and other disadvantaged individuals and households access decent and affordable housing. It examines programs and policies that subsidize housing for low-income households or that attempt to break down institutional barriers, such as discriminatory practices in the real estate industry that impede access to housing.

The book is intended to be a general overview of housing policy. It is beyond its scope to delve deeply into programmatic details or to cover all aspects of the field in equal depth. The focus is on federal and, to a lesser degree, state and local programs and policies that subsidize housing for low-income households or otherwise attempt to make housing accessible to this population. Much less attention is given to policies concerned with the physical aspects of housing, such as design standards and building regulations—except when they are explicitly employed to promote affordable housing. The book does not examine in detail the operation of housing markets or provide a comprehensive legislative history of housing policy.

Although the field of housing policy is relatively small—especially in comparison to such areas as health care and education—it is fragmented and specialized. Most of the field’s literature is technical and focused on particular subtopics, such as public housing redevelopment, the expiration of federal housing subsidy contracts, mortgage lending regulation, homelessness, racial discrimination, and, most recently, mortgage foreclosure. Although these studies certainly cover key topics in housing policy, they do so at greater length, at a higher level of detail, and with more technical jargon than is desirable for a general introduction to the field. I hope this text can serve as a guide to housing policy and provide a point of departure to more specialized readings.

Why Housing Matters

Few things intersect with and influence as many aspects of life as housing does: it is far more than shelter from the elements. As home, housing is the primary setting for family and domestic life, a place of refuge and relaxation from the routines of work and school, a private space. It is also loaded with symbolic value, as a marker of status and an expression of style. Housing is also valued for its location, for the access it provides to schools, parks, transportation, and shopping; and for the opportunity to live in the neighborhood of one’s choice. Housing is also a major asset for homeowners, the most widespread form of personal wealth.

Although good housing in a good neighborhood is certainly no guarantee against tragedy or misfortune, inadequate housing increases one’s vulnerability to a wide range of troubles. Physically deficient housing is associated with many health hazards. Ingestion of lead paint by children can lead to serious learning disabilities and behavioral problems. Dampness, mold, and cold can cause asthma, allergies, and other respiratory problems, as can rodent and cockroach infestations. Inadequate or excessive heat can raise the risk of health problems such as cardiovascular disease (Lubell, Morley, Ashe, & Merola 2011; Lubell, Crain, & Cohen 2007; Cohen 2011; Acevedo-Garcia & Osypuk 2008; Bratt 2000; Kreiger & Higgens 2002; Newman 2008a, 2008b).

Research on the link between housing conditions and mental health is less extensive, but also indicates adverse consequences from inadequate or crowded conditions. Unstable housing conditions that cause families to move frequently are stressful and often interfere with education and employment (Been, Ellen, Schwartz, Steifel, & Weinstein 2010; Lubell, Crain, & Cohen 2007; Lubell & Brennan 2007; Rothstein 2000). When low-income families face high rent burdens, they have little money left to meet other needs. Vulnerability to crime is strongly influenced by residential location. People who live in distressed neighborhoods face a greater risk of being robbed, assaulted—or worse—than inhabitants of more afluent areas (Bratt 2000).

Perhaps the importance of housing for the well-being of individuals and families is brought into sharpest relief in light of the depredations of homelessness. The homeless are at much greater risk of physical and mental illness, substance abuse, assault, and, in the case of children, frequent and prolonged absences from school. The mere lack of a mailing address makes it immeasurably more difficult to apply for jobs or public assistance, or to enroll children in school (Bassuk & Olivet 2012; Bingham, Green, & White 1987; Cunningham 2009; Hoch 1998).

Housing and the Environment

As a major part of the national economy and the predominant land use, housing affects the environment profoundly. For one, it is a major source of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gas emissions, the principal cause of global warming. Residential heating, cooling, and electrical consumption alone accounted for 17% of all greenhouse gas emissions in the United States in 2011 (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 2013: Table ES-8). Housing also accounts for a major portion of the greenhouse gases generated by transportation, which comprised 27% of total emissions in 2011 (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 2013: Table ES-8; see also Ewing & Rong 2008). “Household travel,” as explained by the Federal Highway Administration, “accounts for the vast majority (over 80%) of miles traveled on our nation’s roadways and three-quarters of the CO2 emissions from ‘on-road’ sources” (Carbon Footprint of Daily Travel 2009).

The amount of greenhouse gases produced by household travel depends on (1) the number and fuel efficiency of cars a household owns; (2) the extent to which people travel by car as opposed to other modes of transportation; and (3) the number of miles driven. Residential settlement patterns influence the latter two of these factors. Densely settled areas, especially when housing is located near workplaces, schools, stores, and other destinations, are most conducive to public transit, walking, and bicycling. And when people do drive, the distances traveled tend to be shorter. For example, the Federal Highway Administration estimates that households residing in very high density areas with 5,000 to 10,000 households per square mile generate about half the CO2 in their daily travel than households residing in very low-density areas with 30 to 250 households per square mile. Moreover, households residing within one-quarter mile of public transit generate about 25% less CO2 through their travel than households living further away (Carbon Footprint of Daily Travel 2009). Similarly, a study of transportation patterns in 83 large metropolitan areas found that after accounting for income and other demographic factors, residents in the most compact regions drove far less than their counterparts in the most sprawling regions. For example, Portland, OR, had 30% fewer vehicle miles driven per resident than did Atlanta, Georgia, one of the least dense metropolitan areas. At a more local scale, a study of travel patterns in King County, Washington found that residents of the county’s most “walkable” neighborhoods drove 26% fewer miles per day than their counterparts in the more auto-dependent sections of the county (Ewing, Bartholomew, Winkelman, Walters, & Chen 2007). If the United States is to succeed in curtailing its greenhouse gas emissions and slow global warming, housing development will need to become more compact and better integrated with other land uses (Ewing et al. 2007). This will require a reversal of longstanding development patterns in which single-family housing is built at increasingly low densities, and housing is segregated from most other land uses.2

The Economic Importance of Housing

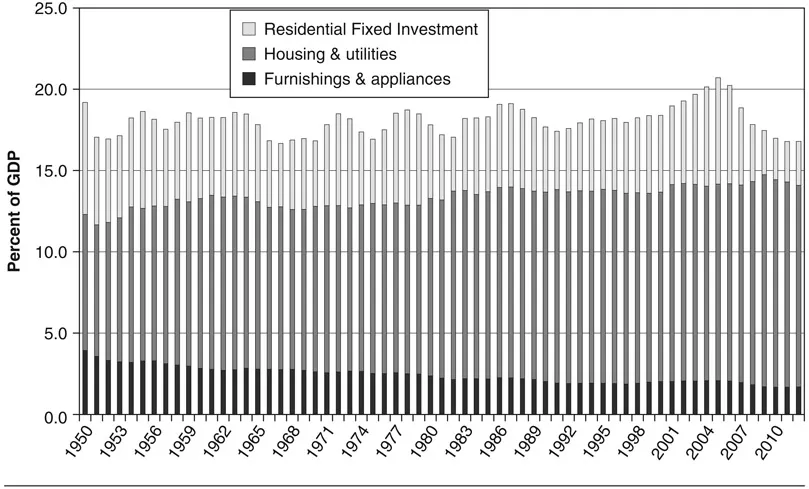

Housing is a mainstay of the U.S. economy, consistently accounting for more than one-fifth of the gross domestic product (GDP) (see Figure 1.1). In 2012, residential construction and remodeling comprised 2.7% of GDP. An additional 12% derived from rental payments, equivalent expenditures made by homeowners, and utilities. Spending on furniture and appliances, contributed another 1.7% to GDP. In total, these three aspects of housing accounted for 16.8% of GDP in 2012 (Bureau of Economic Analysis 2013a). However, as Figure 1.1 shows, the housing sector had previously comprised a larger share of the economy. As discussed in Chapter 2 and throughout the book, the housing market was extremely depressed from 2007 through 2011 as a result of the collapse of the housing bubble and the subsequent recession. In the mid-2000s, the peak years of the housing bubble, the sector accounted for more than 20% of GDP.

The total value of the nation’s privately owned housing stock, at $17.6 trillion in 2011, accounted for half of the value of privately owned fixed assets and consumer durable goods (Bureau of Economic Analysis 2013b). Residential construction in 2008 accounted for about 4.9 million jobs, $368 billion in income, and $142 billion in federal, state, and local tax revenue (Liu & Emrath 2008).

At the local and regional level, housing is also critically important. The construction, development, and sale of housing generate employment, income, and tax revenue. In addition to the employment and income generated directly through construction activity, housing development generates indirect economic benefits from the expenditures of construction workers and vendors on locally supplied goods and services. Other economic benefits derive from the consumer spending of the households residing in new housing. The National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) estimates that construction of 100 new single-family homes in the average metropolitan area generates about 324 full-time-equivalent jobs for the local community during the construction period and about $21 million in income for local businesses and workers. The subsequent expenditures of the households that come to live in these 100 new homes generate an additional 53 jobs and $743,000 in income annually (National Association of Home Builders 2009).

Figure 1.1 Housing’s contributions to GDP, 1950–2012. Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis 2013.

Residential construction is also a major source of revenue for all levels of government. Nationally, single-family home building generated about $118.2 billion in taxes and fees (estimate based on NAHB estimates and housing completions data) (Liu & Emrath 2008). The development of 100 single-family homes generates about $2.2 million in local government revenue during the year of construction. Afterward, the 100 units generate about $743,000 annually for local governments through property taxes as well as other taxes and fees paid by homeowners (National Association of Home Builders 2009).

The housing sector helped sustain the national economy during the weak recovery that followed the recession of 2000, but it was also a key element behind the economy’s severe recession that began in 2007. Prior to 2006, extraordinary increases in house prices, especially along the East and West coasts, generated huge amounts of economic activity—through home sales, renovations and remodeling, and mortgage refinancing. With home prices increasing at an annual rate of 10% or higher, homeowners tapped into their home equity to retire other debts, pay for home improvements, capitalize small busine...