![]()

Part 1

What on Earth Are We Doing?

The goal of this first section of the book is to familiarize readers with the current ecological crisis and its origins, as well as provide a vision for a sustainable future. Chapter 1 reviews some of the principal ways humans are living unsustainably; it serves as a primer on environmental science. Chapter 2 contextualizes the current ecological crisis with a historical survey of relevant cultural, technological, economic, and political developments; it represents environmental studies. Chapter 3 presents foundational principles grounded in ecology, followed by examples of behaviors and systems compatible with these principles; this chapter is an introduction to sustainability.

![]()

Chapter 1

There Are No Environmental Problems

• Biology’s Bottom Line: Carrying Capacity

• Overconsumption: Our Ecological Footprint

• Energy

• Water

• Food

• Material Goods

• Conclusion

The environmental crisis is an outward manifestation of a crisis of mind and spirit. There could be no greater misconception of its meaning than to believe it is concerned only with endangered wildlife, human-made ugliness, and pollution. These are part of it, but more importantly, the crisis is concerned with the kind of creatures we are and what we must become in order to survive.

(Lynton K. Caldwell, quoted by Miller, 2002, p. 1)

What will your future be like? If you are similar to your peers, you have hopes of a happy life with your family and friends. 1 You desire good physical health and your own comfortable space in which to live. You expect to own more—and better—things than you currently do. You plan to travel. And, of course, you assume you will have easy access to basic necessities like electricity, heat, food, and water.

Yet, you might also have a notion, ranging from an inkling to a grave fear, that this scenario is threatened, that your future might not be so rosy. If this has not occurred to you, just skim the local, national, and world news with your eyes peeled for stories about energy debates, toxic pollution, nuclear waste, species extinctions, water shortages, overflowing landfills, plastic gyres in the oceans, topsoil loss, over-population, and a changing climate. As you educate yourself, you will begin to realize that many aspects of our 2 current lifestyles simply cannot be taken for granted or maintained long-term, particularly for those of us who live in the United States. The sobering fact is that because of the way we are living, we are severely compromising planetary resources, and consuming them too quickly and carelessly to keep demand in balance with the supply. If Mother Earth had a Facebook page, her status update would be, “WTF, peeps?”

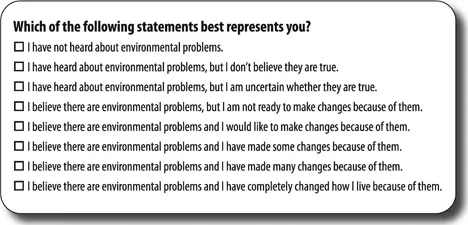

Figure 1.1 Readiness to change.

Large surveys suggest that at least some people are aware of these problems. For example, the most recent Yale survey on Climate Change in the American Mind found that two-thirds of Americans believe global warming is happening; about the same number think it will cause harm to future generations of people and to other species; 40% think it is a threat to themselves, their families, or their local communities; and one in three think it is already hurting people in the United States (Leiserowitz, et al., Climate change in the American mind, 2014). But just knowing about the problems doesn’t mean people are ready to take action (see Figure 1.1).

Compared to a couple of decades ago, more people are doing little things such as recycling their newspapers, bottles, and cans, but when it comes to the big picture, most people generally behave according to established habits. A vague sense of pessimism about the future coexists with a “business as usual” attitude. For example, in spite of the fact that about half of Americans say they are “worried” about global warming (Leiserowitz, et al., Climate change in the American mind, 2014; Saad, 2013), most people continue to routinely drive rather than walk or bike, take vacations across the country and around the world, heat their homes to 72 degrees, use leaf blowers instead of rakes and dryers instead of clotheslines, throw usable stuff away, buy new stuff … and try not to think about the fact that the planet cannot possibly support all of this for much longer.

Not surprisingly, people have difficulty contemplating planetary collapse. We find it too depressing, too overwhelming, perhaps too terrifying. So, we turn our attention to present concerns such as family obligations, work or school, and paying bills. Such a response is understandable and consistent with an evolutionary perspective. Human perceptual systems evolved in an environment where threats were sudden and immediate; our ancient ancestors had no need to track gradually worsening problems that took many years to manifest. As a result, the human species is shortsighted and has difficulty responding to potentially catastrophic, but slowly developing, harmful conditions. Rather than working to prevent crises, people have a strong tendency to delay action until problems are large scale and readily apparent, at which time they attempt to respond. Unfortunately, by then, it may be too late.

Despite such hardwiring, the human species is capable of dramatic and rapid cultural evolution, as the pace of the agricultural, industrial, and technological revolutions reveals. For example, as undergraduates, the four of us authors used typewriters for papers after spending hours searching printed publication indexes to find citations for journal articles that we had to track down in the stacks of bound periodicals. Now, it feels normal to us to use high-speed computers, online databases with full-text pdf files, and electronic networking and file sharing tools. The point is this: Humans are quick to adapt. The human capacity for rapid change could reverse current ecological trends, given sufficient public attention and political will (Ehrlich & Ehrlich, 2008).

Many people reassure themselves that technological fixes will save the earth, but while technological and engineering expertise is certainly needed to reverse ecological damage—just as such knowledge was used to produce it—the problems that threaten the survival of life on this planet are too huge, too complicated, and too urgent to be solved by advances in technology alone. Human beings have always altered their physical environment in order to survive, but the pace and scale of current environmental change knows no precedent. And the longer people wait to take action, the worse the problems will become. Most importantly, pinning hopes on technology misses the primary cause of the current predicament and the crucial tool for lasting solutions: human behavior.

The theme of this book is that all so-called environmental problems are actually behavioral problems. Ecological systems don’t have problems in and of themselves; the problems stem from people’s behaviors as consumers, corporate decision makers, city planners, and governmental legislators. Ecologically incompatible beliefs, values, worldviews, and actions are ultimately responsible for the rapid deterioration of the natural systems on which every creature depends for survival. Thus, these problems require more than just technological solutions. As individuals, we need to make changes in how we satisfy our needs and fulfill our desires, how we express ourselves and our values, how we participate in our communities, how we experience our relationship to nature, and even, perhaps, in how we understand the meaning of our lives.

You probably are somewhat familiar with the contemporary ecological crisis. Still, in order to provide a foundation for the rest of the book, the following sections represent an overview of several of the big issues confronting humanity. The scope is limited in the interest of space, but should give you at least some idea of the challenges that lie ahead.

Biology’s Bottom Line: Carrying Capacity

It may surprise you to learn that the first scientific calculations of global warming due to human emissions of carbon dioxide were published back in 1896 (Weart, 2013). In 1914, the North American passenger pigeon was declared extinct due to hunting, yet this species had once been so abundant that flocks blackened the entire sky as they took hours to pass overhead (Blockstein, 2002). By the 1930s, negative health effects of new, toxic substances such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) were being reported in factory workers and confirmed in laboratories (Versar, Inc., 1979). Indeed, for more than 100 years, scientists have documented anthropogenic (human caused) threats to the survival of the biosphere, a term coined in 1875 to mean the entire global ecosystem and all of its inhabitants.

As you will read in Chapter 2, however, widespread public awareness of these problems was not raised until the 1960s. Even some scientists were slow to recognize how industrial activities such as burning fossil fuels and synthesizing chemicals were having serious systemic repercussions. But by 1992, 1,670 prestigious scientists, including over 100 Nobel Laureates, had signed a “World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity,” urging public attention to the “human activities that inflict harsh and often irreversible damage on the environment and on critical resources” (Union of Concerned Scientists, 1992). Today, it is very clear that the planet and all of us who reside here are in dire straits.

A fundamental concept for understanding what is happening is carrying capacity, a term used by biologists to describe the maximum number of any species a habitat can support. If the territory is isolated and the population cannot migrate to a new one, the inhabitants must find a way to live in balance with its resource base. Alternatively, if the population grows too quickly so that it depletes its resources suddenly, the population will crash.

Such crashes have happened in both nonhuman and human populations. Islands, which segregate ecosystems and prevent migration, provide the clearest examples. For instance, in 1944, the U.S. Coast Guard imported 29 yearling reindeer to the isolated St. Matthew Island in the Bering Sea (between Alaska and Russia). The island was ideal for the propagation of reindeer, so by 1963, the population had grown from 29 to over 6,000. However, the terrain became badly overgrazed, food supplies dwindled, and the population crashed in the winter of 1964. The island could have supported about 2,300 reindeer, but after the crash, only 3% of that figure survived (Catton, 1993).

Archaeological evidence from Easter Island, off the coast of Chile, shows that a very complex human population grew there for 16 centuries. To support themselves, the islanders cut more and more of the surrounding forests so that eventually soil, water, and cultivated food supplies were depleted. The population crashed in the seventeenth century, falling from 12,000 in 1680 to less than 4,000 by 1722. In 1877, only 111 people still survived (Catton, 1993). On the mainland, some human population crashes have been hastened by the fact that societies weakened by resource shortages become more vulnerable to being wiped out by other humans. However, the Sumerians of Mesopotamia and the Maya of the Yucatan region provide two clear examples of crashes due simply to exceeded carrying capacity.

The Sumerians were the first literate society in the world, leaving detailed records of their civilization and its decline between 3000 and 2000 B.C. The complicated agricultural system that supported their population also depleted the quality of their soil through salinization and siltation. In the words of environmental historian Clive Ponting (1991):

The artificial agricultural system that was the foundation of Sumerian civilization was very fragile and in the end brought about its downfall. The later history of the region reinforces the point that all human interventions tend to degrade ecosystems and shows how easy it is to tip the balance towards destruction when the agricultural system is highly artificial, natural conditions are very difficult, and the pressures for increased output are relentless. It also suggests that it is very difficult to redress the balance or reverse the process once it has started.

(p. 72)

Similarly, the Maya, who developed what are now parts of Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras, built a complex civilization on the fragile soil of tropical forests. Clearing and planting supported a population from 2000 B.C. to A.D. 800. As the population grew, land was not allowed time to recover between plantings. The deforestation caused significant changes in weather patterns, further reducing crop yields. In about A.D. 800, the population crashed; within a few decades, cities were abandoned, and only a small number of peasants continued to survive in the area.

In the past, population crashes have occurred in one part of the world without seriously affecting people in other regions. Today, however, the threat of a crash on ...