eBook - ePub

Gender Inequality in Our Changing World

A Comparative Approach

- 462 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Gender Inequality in Our Changing World

A Comparative Approach

About this book

Gender Inequality in Our Changing World: A Comparative Approach focuses on the contemporary United States but places it in historical and global context. Written for sociology of gender courses, this textbook identifies conditions that encourage greater or lesser gender inequality, explains how gender and gender inequality change over time, and explores how gender intersects with other hierarchies, especially those related to race, social class, and sexual identity. The authors integrate historical and international materials as they help students think both theoretically and empirically about the causes and consequences of gender inequality, both in their own lives and in the lives of others worldwide.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gender Inequality in Our Changing World by Lori Kenschaft,Roger Clark,Desiree Ciambrone in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

What Is Gender?

Introduction

If you had lived in 1900 nearly every aspect of your days would be shaped by gender, though the details of what that meant varied greatly from place to place. If you were a white woman living in an American city, for example, you might have a job for a few years before you married, but afterwards you were expected to stay home and raise children. If you were an American man you were expected to spend most of your waking hours working to support your family. Around the world, men had nearly all official authority: women were excluded from nearly all political and corporate positions, only men could vote in almost all elections, and most religious communities did not ordain women or allow them to speak during a worship service. Wives everywhere were expected to obey their husbands. People everywhere worked and socialized primarily with others of their own gender. Most colleges did not admit women, and those that did often segregated them in the classroom. In short, gender differences were strong and obvious, and most people took gender inequality for granted.

Today, gender is much less salient in the organization of the United States and many other countries. Women now work in almost every profession: they are politicians, executives, scientists, and clergy (though some religions still do not allow women to be clergy). Most American mothers work for pay, and growing numbers of men feel that being a good father means far more than just being a good provider. American men and women socialize freely, and many people have close cross-gender friendships that are not romantic. Nearly everyone has classmates or colleagues of the other gender.

Gender inequality still exists, however. Men still hold the large majority of high-income and high-power positions: most politicians, CEOs, investment bankers, celebrated athletes, and so on are male. American women persistently earn less than men, even if they work full-time in the same occupations with the same education. Mothers are widely seen as having ultimate responsibility for their children, and women still do most childcare and housework. The unequal division of parenting accounts for some of the income gap between women and men, but even young women without children earn less than similar men (BLS, 2012; Correll, 2013; Coontz, 2012).

Gender greatly affects patterns of violence. Around the world, men are much more likely than women to be perpetrators of violence, while women are more likely to be victims of sexual violence and violence by an intimate partner. Nearly one in five American women has been raped, compared to about one in 71 American men (Black et al., 2011: 1). A quarter of American women report they have experienced serious physical violence from an intimate partner sometime in their lives, compared to an eighth of American men (Breiding et al., 2014: 2). Men, however, are more likely to die from violence (WHO, 2011a). In the United States, white men are more than twice as likely as white women to be murdered, while black men are nearly six times as likely as black women to be murdered (FBI, 2010). As we will see later, violence against both women and men is often driven by gender.

Gender inequality varies greatly around the world, but in some places it is intense. In 15 countries a married woman may not take a job without her husband’s permission, and in 25 countries she may not decide where to live. In five countries her husband exclusively owns and controls the household’s money, land, and property – even if she earned the income (World Bank, 2013b: 16, 29). About 250 million women were married before the age of 15, nearly always in a marriage arranged by their families, often without their consent. More than a quarter of the women in India were married by the age of 15, as were nearly 40 percent in Bangladesh – and the percentage is rising in Iraq and other war-torn countries where parents feel they cannot feed their daughters or protect them from rape (UNICEF, 2014; Brown, 2014). Some of these girls have not even reached puberty before they are required to have sex with their husbands whenever he wishes (Ali et al., 2010). A third of South African men and a quarter of Indian men admit that they have raped a woman or girl (Jewkes et al., 2012; Barker et al., 2011: 46). In China more than a million female fetuses were aborted in 2008 because the couple wanted a son (World Bank, 2011a: 15). In Chad one in 15 women dies in childbirth (WHO et al., 2012: 32). In southern Asia only half of the adult women can read and write, compared with three-quarters of the men (UNESCO, 2010).

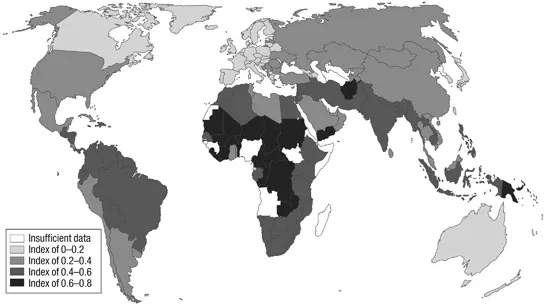

Trying to rank which countries have more or less gender inequality is a vexed venture. Figure 1.1, for example, is based on the United Nations’ Gender Inequality Index, which makes Saudi Arabia and the United States look comparable. Saudi women tend to be better educated than Saudi men (partly because young women have few options other than studying), they are better represented in the Saudi Shura Council than the U.S. Congress (though Saudi Arabia is really ruled by the Saudi family), and their rates of teen pregnancy and death in childbirth are low (both good things). Together, these factors give Saudi Arabia a moderately good score. This index does not take into account numerous less measurable factors, such as social segregation of the genders or the requirement that every adult Saudi woman have a male guardian. No index can take into account the frequency and severity of gender-related violence against women, as comparable international data simply do not exist. Any comparisons of gender inequality therefore need to be interpreted thoughtfully.

Figure 1.1 United Nations Gender Inequality Index, 2013 (UNDP, 2013a)

Many different observations suggest, however, that gender inequality tends to be highest in Africa, the Middle East, and southern Asia, and lowest in wealthy countries. Latin American countries historically had quite high levels of gender inequality, as well as other forms of inequality, but they have changed rapidly in recent decades and most are now more moderate. The Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden) often come out at or near the top in measures of gender equality, but even there gender inequality persists. Only 6 percent of Norwegian companies, for example, have a female chief executive (Economist, 2014n).

The United States has more gender inequality than most wealthy countries, and ranks worse than many middle-income countries on a variety of measures. Men and women are more likely to receive the same pay for the same work, for example, in 64 other countries (WEF, 2014: 65). As of July 2014, 103 countries had a higher percentage of women in their national legislatures (Inter-Parliamentary Union, 2014). Women are five times as likely to die in childbirth in the United States as in Sweden, and 49 countries have lower maternal death rates (WHO et al., 2012: 32–36). We will say more about these and many other topics later. For now, however, it is enough to point out that the United States is not an exemplar of gender equality.

The first four chapters of this book will offer several theories about the root causes of gender inequality. Some people believe that the origins of gender inequality are fundamentally economic: men’s and women’s different access to material resources and the power and respect that often accompany them. Other people believe the crux of the issue is family structures: how families regulate inheritance, marriage, childrearing, and so on. Other people believe that gendered violence is at the heart of all other forms of gender inequality. And other people believe that control of sexuality is the key issue. One simple definition of a theory is a way of thinking that identifies, explains, and predicts patterns in a wide range of observations, and all of these theories are supported by many observations made in many different contexts. We will not provide one unified “theory of gender inequality,” because we have found the world more complicated than any one perspective can encompass. We therefore offer a variety of perspectives – you might think of them as mental tools – that we believe are helpful. We believe that all of these theories have merit and are worth your consideration.

What Is Gender? Seven Perspectives

First, though, we need to address an even more basic question: What is gender?

Social scientists typically use the term sex to refer to the reproductive biology that humans are born with – the organs, genetics, hormones, and secondary sex characteristics that enable new human beings to be born – while they use the term gender to describe how people understand the social and cultural significance of sex. Like many words, however, sex and gender have multiple meanings and connotations. Americans today may use one or more of at least seven different mental frameworks for understanding gender. We believe it is important to have a basic understanding of each of these seven frameworks, though you are likely to find some of them more plausible than others.

Essentialist Perspectives

Many traditional cultures, including the United States historically, saw sex and gender as a seamless whole. People believed that women and men had fundamentally different talents, tastes, desires, and destinies. These gender differences, they believed, were created by God and/or nature, and were simply part of reality. This perspective is often called essentialism, as it suggests that women and men are different in their essences – not just in their reproductive capacities, but also in their basic human natures. In this framework, sex and gender are considered synonyms, but people often prefer to use the word “gender” as a euphemism for the more earthy “sex.”

The naive forms of essentialism have been widely discredited. Anyone who is reasonably well informed now acknowledges that gender varies in different cultures and changes over time, so gender is not an immutable creation of either God or nature. Many feminists look skeptically at any hint of essentialism, as essentialist arguments have often been used to justify existing practices and hierarchies. The idea that men are naturally inclined to rape, for example, has been used to argue that women should stay out of men’s way rather than holding rapists accountable for their actions. Here and in many other examples, the belief that men and women are essentially different serves to perpetuate gender inequality.

One reason that essentialist arguments persist is that culture goes very deep into people’s psyches. People often draw conclusions about differences between men and women by observing the people around them, but just because something is ubiquitous in one time and place does not mean it is universal. If you grow up inside a culture, the expectations of that culture will often seem intuitively obvious to you – like “second nature.” Many American men, for example, feel uncomfortable if they travel to parts of Asia where men wear sulus, sarongs, or other garments that to American eyes look like skirts, especially if they try to dress like the local men. While their rational brains may tell them that clothing is a cultural phenomenon, their emotions may still insist that wearing a skirt is unnatural. Just because something is cultural does not mean it is easy, or even possible, to change at will – and just because a behavior feels natural does not mean that it is. In these cases, essentialist arguments give us important insights into people’s subjective experiences, but not into the underlying nature of gender.

A subtler variant of essentialism, sometimes called evolutionary psychology, suggests that males and females have come under different evolutionary pressures because of their different roles in physical reproduction. In its rigid forms, evolutionary psychology can suggest that human behavior is static and predetermined, a belief that nearly all social scientists reject. In its more nuanced forms, however, it speaks of propensities and patterns. Take, for example, the easily measured physical characteristic of height. Men tend to be taller than women, on average, but we all know that some women are taller than some men. Height is also affected by non-genetic factors, such as nutrition. If you want to reach an item on a high shelf, it makes sense to ask the tallest person in the room, not the nearest man. And yet it is true that, on average, men tend to be taller than women. Some scholars argue that we should not ignore the possible role of biology in the rare gender patterns that seem to be universal, such as men’s greater propensity toward violence. Using evolutionary history to explain human behavior is fraught with challenges, as people often develop theories that fit their pre-existing beliefs, but nor should we rule out the possibility that biology affects behavior and therefore culture.

Constructivist Perspectives

Most social scientists are constructivists, which means they believe gender is created by culture, not by God or nature. Every person is born into a particular society, or human community, each of which has its own culture, or characteristic ways of thinking, feeling, and behaving. By the age of three children are beginning to learn and follow (at least some of the time) the gendered codes of their culture. Social scientists (including the authors of this book) underline the distinction between sex and gender by using the terms male and female to refer to people’s biological sex and masculine and feminine to refer to gender.

Many constructivists describe social life as an improvisational performance. Children learn the expectations of their society, but no one just follows those expectations. Indeed, it would be impossible to do so, as no society scripts word-for-word every possible scenario. Instead, we learn patterns of behavior that we draw upon as we go through our days and interact with other people. In a sense we are all actors, engaged in a performance both for other people and for ourselves. How we perform affects how others perform for us, and vice versa. Through these improvisational performances we create and re-create a shared world of meanings, symbols, and significance (Goffman, 1959).

Constructivists often refer to people as “performing gender” or “doing gender” to underline that gender is something that people continually create (e.g. West and Zimmerman, 1987; Butler, 1990). Women in many cultures, for example, are expected to keep their legs together and women often sit and stand in ways that minimize the space they occupy. Men, meanwhile, are expected to spread their legs and arms and take up an abundance of space. Such “gender displays” both indicate the individual’s adherence to their community’s norms and reinforce those norms (Goffman, 1979). Most people display their gender through their clothing, hairstyles, cosmetic use (or lack thereof), the timbres of their voices, the way they walk, and many other nuances of behavior. They thus assist each other in quick and easy gender categorizations.

Not everyone, of course, always follows the codes. Many people sometimes play with gender symbols in a spirit of humor. Some people regularly incorporate ways of being that are associated with the other gender into their own personal style. Although some communities tolerate, or even celebrate, individuals who flout gendered conventions, gender-nonconforming individuals may be subjected to social pressures that range from ridicule to ostracism, violence, and even murder. Most people therefore try to achieve a credible performance of the “correct” gender. Even the most gender-conforming individuals, however, do not always perform to type. Sometimes expectations are self-contradictory, and sometimes people enact behaviors associated with the other gender because they feel they are called for by the situation. The most macho police officer, for example, may display a tender “motherly” style when comforting a grieving child.

Most but not all feminists are constructivists. Many feminist achievements have been predicated on the belief that gender is a cultural category and therefore subject to change. In 1900, for example, women always wore skirts and no woman had ever served on the U.S. Supreme Court. Now, there are women on the Supreme Court who wear pants underneath their judicial robes and act very similarly to the men on the Court. Their presence is a profound challenge to the gender roles of a previous generation, and many people can remember a time when no women had ever served on the Court. (Sandra Day O’Connor, the first female Justice, was appointed by Ronald Reagan in 1981.) But most women nowadays, when they wear pants or aspire to professional careers, see themselves not as wanting to be a man, but as a woman who wants to do things that men traditionally did. The belief that gender can change is thus rooted in the belief that gender is a cultural construct, not natural or God-given.

Not all constructivists, however, are feminists. Some theorists argue that gender performances are often a source of pleasure for the individuals involved, so feminists should not be so hasty to criticize them or try to eliminate them (Paglia, 1990). Feminists tend to focus on gender inequality, meaning hierarchies based on gender, and male privilege, the advantages that come to men simply by virtue of being men. Sometimes, though, gender codes are just a matter of difference: men’s shirts button one way, women’s another way, and we all get dressed just fine. Constructivists who focus on difference rather than inequality may feel that gender is something to enjoy, even celebrate, rather than challenge or critique.

Doubly Constructivist Perspectives

Some people argue that even the concept that there are two biological sexes is a cu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- Preface: Gender Inequality in Our Changing World

- CHAPTER 1 Introduction: What Is Gender?

- PART I FOUR CORE ISSUES

- PART II CONSEQUENCES

- PART III CONTINUITY AND CHANGE

- PART IV LOOKING TOWARD THE FUTURE

- Glossary

- References

- Index