- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Forensic Anthropology Training Manual

About this book

Provides basic information on successfully collecting, processing, analyzing, and describing skeletal human remains.

Forensic Anthropology Training Manual serves as a practical reference tool and a framework for training in forensic anthropology.

The first chapter informs judges, attorneys, law enforcement personnel, and international workers of the information and services available from a professional forensic anthropologist. The first section (Chapters 2-11) is a training guide to assist in the study of human skeletal anatomy. The second section (Chapters 12-17) focuses on the specific work of the forensic anthropologist, beginning with an introduction to the forensic sciences.

Learning Goals

- Upon completing this book readers will be able to:

- Have a strong foundation in human skeletal anatomy

- Explain how this knowledge contributes to the physical description and personal identification of human remains

- Understand the basics of excavating a grave, preparing a forensic report, and presenting expert witness

- testimony in a court of law

- Define forensic anthropology within the broader context of the forensic sciences

- Describe the work of today's forensic anthropologists

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Forensic Anthropology Training Manual by Karen Ramey Burns in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction to Forensic Anthropology

CHAPTER OUTLINE

Introduction: The Problem of the Unidentified

Discipline of Forensic Anthropology

Objectives of an Anthropological Investigation

Cause and Manner of Death

Stages of an Investigation

INTRODUCTION: THE PROBLEM OF THE UNIDENTIFIED

The body of knowledge known as forensic anthropology offers a unique humanitarian service to a world troubled by violence. Clandestine deaths cast a shadow on everyone. Missing persons and unidentified dead—the “disappeared” of this world—are too often the result of the worst criminal and political behavior of humankind. Peace and humanity begin with the effort to identify the dead and understand their fate.

WHO ARE THE “MISSING, UNIDENTIFIED, AND DISAPPEARED”?

Some unidentified bodies are those of derelicts who simply wandered off and died. Some are suicides who didn’t want to be found. But many are unresolved homicides, hidden long enough to assure impunity for the perpetrators. The unidentified may be teenagers executed by gang members, women raped by soldiers, or children abused by caretakers. They are sometimes the evidence of serial killers who walk the streets without fear. In many countries, the missing and unidentified are known as “the disappeared.” They are the result of genocide and extreme misuse of authority.

The odd thing about an unidentified body is its silence. It may seem that all dead bodies are silent, but an unidentified body is even more silent. No one calls and complains when it is forgotten. No one exerts pressure or wields political or financial power on behalf of an unidentified person. If shipped off to a morgue and buried as a “John Doe,” it doesn’t even take up space at a responsible agency.

It appears that no one cares, but this is not true. Those who care suffer in silence with nowhere to turn for relief. They suffer the agony of not knowing the fate of their loved ones. They put their lives on hold. They become victims who are afraid to move to a new location, to remarry, or to rebuild their lives. They feel that they might show a lack of love by giving up hope and assuming the person to be dead. After all, what if the person does return and finds his or her home gone?

Parents of soldiers missing in action say that not knowing is far worse than being able to grieve. Instead of feeling buoyed by hope, they are paralyzed by the fear that their child is suffering somewhere.

Families of missing persons say that they experience a sense of relief when the bodies of loved ones are finally identified. They find a sense of closure and even empowerment through the process of funeral rituals.

WHY IS IDENTIFICATION SO DIFFICULT?

The general attitude of law enforcement personnel toward unidentified bodies tends to be defeatist. Standard comments are, “If it is not identified within two weeks, it won’t be identified,” or “If it is not a local person with a well-publicized missing person record, forget it.” These are self-fulfilling prophecies. While the law of diminishing returns is no doubt applicable, the door can be left open for success. However, leaving the door open is not easy. It requires a thorough analysis of the remains and maintaining a record of correct information.

Unfortunately, correct information is as useless as incorrect information if it is not communicated. This may be the Information Age, but the world is still struggling with the practical and responsible use of information. The technology is available, but intelligent use of technology is a challenge. Within the United States, the National Crime Information Center is a good place to store and search for information, especially when used in combination with NamUs, a recent web-based system of missing and unidentified persons databases. In developing countries, similar databases are also being established. This is being accomplished with slow determination by local activists and numerous international agencies as well as nongovernmental organizations such as the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Physicians for Human Rights, and the Carter Center of Emory University.

When the doors are left open for identification, and an identification is finally made, the remains must be relocated. Storing human remains (especially decomposing remains) is not as easy as storing most other types of evidence, but it can be done. However, the ethics of the situation are controversial. Is it more important to identify a deceased person, inform the family, and possibly apprehend a murderer, or is it more important to “honor” the dead with an anonymous burial?

THE DISCIPLINE OF FORENSIC ANTHROPOLOGY

Forensic anthropology is best known as the discipline that applies the scientific knowledge of physical anthropology (and often archaeology) to the collection and analysis of legal evidence. More broadly speaking, it is anthropological knowledge applied to legal issues. Forensic anthropology began as a subfield of physical anthropology but has grown into a distinct body of knowledge, overlapping other fields of anthropology, biology, and the physical sciences.

Recovery, description, and identification of human skeletal remains are the standard work of forensic anthropologists. The condition of the evidence varies greatly, including decomposing, burned, cremated, fragmented, or disarticulated remains. Typical cases range from recent homicides to illegal destruction of ancient Native American burials. Forensic anthropologists work individual cases, mass disasters, historic cases, and international human rights cases.

Forensic anthropologists are also called to work on cases of living persons where identity or age is in question. Comparisons of video tapes, photographs, and radiographs are within the capability and experience of most forensic anthropologists.

HISTORY OF FORENSIC ANTHROPOLOGY

The public views forensic anthropology as a young discipline, and it is. However, it has a long developmental history in the works of physical anthropologists fascinated by the anatomical collections of museums and universities. Anthropologists were making observations about skeletal differences and writing papers for professional societies decades before any legal application for their knowledge was ever considered. The earliest beginnings of what we call forensic anthropology can be attributed to a few bright attorneys mired in complicated legal battles. They searched out the knowledge they needed to win and made use of it in court. Little by little, over the last 150 years, anthropologists have responded with goal-driven research. Along the way, they learned about the work of law enforcement investigators, the capabilities of other forensic scientists, and the requirements of a courtroom environment.

There is no date for the beginning of the study of human skeletons, but there is a firm date for the first use of skeletal information in a court of law—the 1850 Webster/Parkman trial. Oliver Wendell Holmes and Jeffries Wyman, two Harvard anatomists, were called to examine human remains thought to be those of a missing physician, Dr. George Parkman. A Harvard chemistry professor, John W. Webster, was accused of the crime of murder. The evidence was substantial even before the anatomists became involved. Webster owed Parkman money; a head had been burned in Webster’s furnace; body parts were found in his lab and privy; and a dentist had identified Parkman’s dentures found in the furnace. (Forensic dentistry was getting a start, too.) Holmes and Wyman testified that the remains fit the description of Parkman, and Webster was hanged.

My favorite case took place a few years later (1897) in Chicago. This time, the expert witness was actually an anthropologist—George A. Dorsey, a curator at the Field Museum of Natural History. Dorsey was called to examine a few bits and pieces of bone from the sludge at the bottom of a sausage-rendering vat. Louisa Luetgert, wife of a sausage factory owner, was missing, and her husband, Adolph, was accused of murder. Again, the evidence was substantial even before the anthropologist became involved. Adolph was seeing another woman; the Luetgert marriage was on the rocks; Adolph had closed down his plant for several weeks; he had ordered extra potash before closing the plant; he had given the watchman time off on the night of the disappearance; and, most incriminating of all, Louisa’s rings were found in the vat. Dorsey had only to prove that the bones were human, not pig, and he did. Adolph Luetgert was imprisoned for life. By the way, this is a good case to support the importance of learning to recognize fragments and all the other tiny “insignificant” bones.

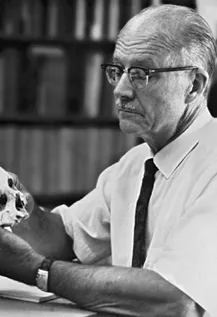

Figure 1.1

Wilton Marion Krogman (right) examining the death mask of a murder victim, 1957. Special Collections Research, Center, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA.

Wilton Marion Krogman (right) examining the death mask of a murder victim, 1957. Special Collections Research, Center, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, PA.

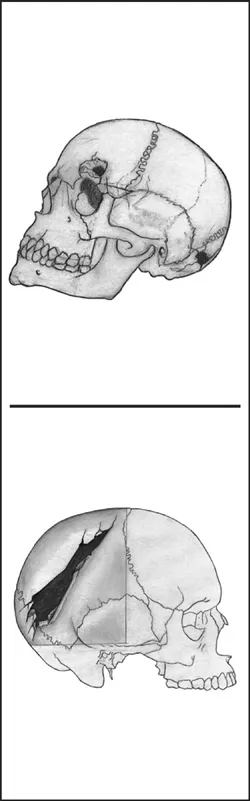

Figure 1.2

T. Dale Stewart. From Human Studies Film Archives, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

T. Dale Stewart. From Human Studies Film Archives, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution.

T. Dale Stewart (1901–1997) designated Thomas Dwight (1843–1911) of Harvard University as the “Father of Forensic Anthropology in the United States.” This is partially based on the fact that Dwight wrote a prize-winning essay on the subject of identification from the human skeleton in 1878. Dwight may not have been the very first actor in what we now call forensic anthropology, but he was the first to publish.

Early in the twentieth century, many anthropologists contributed to the developing discipline, but Wilton Marion Krogman (1902–1987) was the first to speak directly to law enforcement with his “Guide to the Identification of Human Skeletal Material,” publishe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Brief Contents

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Chapter 1 Introduction to Forensic Anthropology

- Chapter 2 The Biology of Bone and Joints

- Chapter 3 The Skull and Hyoid

- Chapter 4 The Shoulder Girdle and Thorax: Clavicle, Scapula, Ribs, and Sternum

- Chapter 5 The Vertebral Column

- Chapter 6 The Arm: Humerus, Radius, and Ulna

- Chapter 7 The Hand: Carpals, Metacarpals, and Phalanges

- Chapter 8 The Pelvic Girdle: Illium, Ischium, and Pubis

- Chapter 9 The Leg: Femur, Tibia, Fibula, and Patella

- Chapter 10 The Foot: Tarsals, Metatarsals, and Phalanges

- Chapter 11 Odontology (Teeth)

- Chapter 12 Introduction to the Forensic Sciences

- Chapter 13 Laboratory Analysis

- Chapter 14 Race and Cranial Measurements

- Chapter 15 Field Methods

- Chapter 16 Professional Results

- Chapter 17 Large-Scale Applications

- Appendix: Forms and Diagrams

- Glossary of Terms

- Bibliography

- Index