![]()

Section II

The Nineteenth Century, 1810–1909

![]()

Chapter 6

The End of Spanish Rule, 1810–1821

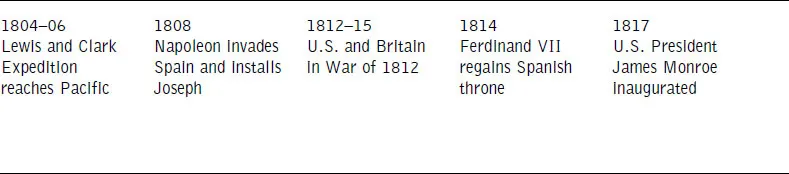

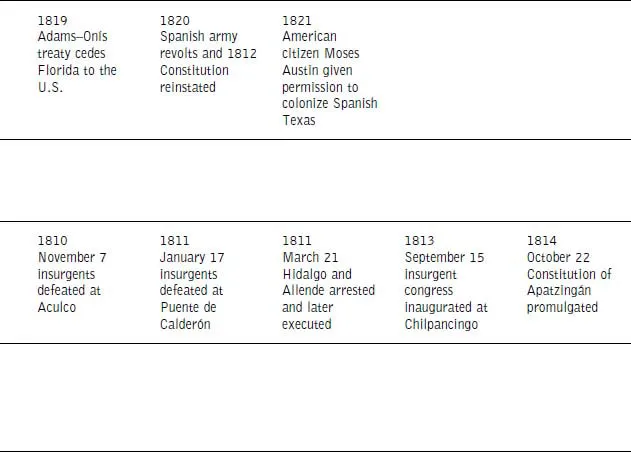

TIMELINE—WORLD

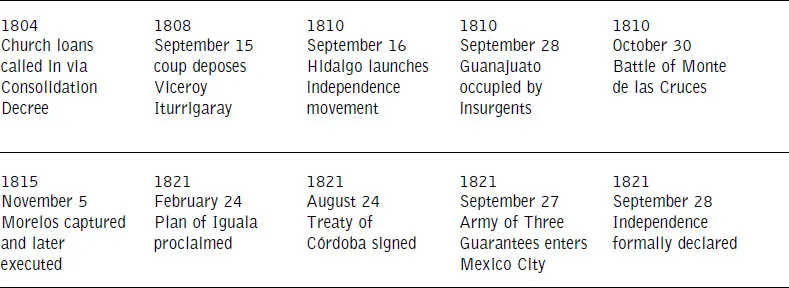

TIMELINE—MEXICO

Latin American independence came in the midst of an era of sweeping change in the Western world. It was indeed part of that change. The Enlightenment, in advertising the potency of human reason, had accustomed those whom it touched to the notion that change was a normal state of being; for what was dangerous, damaging, or demeaning in the human condition could be remedied by the proper application of the mind’s power.

(P. J. Bakewell, 1997)

THIS CHAPTER FIRST CONSIDERS GRIEVANCES THAT ACCUMULATED during the first decade of the nineteenth century. These grievances led to a revolt led by two priests, Miguel Hidalgo and José María Morelos. After royalist forces repeatedly defeated rebel armies, the insurgents turned to guerrilla warfare. In response to the rebellion, the Crown sought to maintain, or regain, Mexicans’ loyalty through such measures as abolishing tribute, allowing elections, and establishing new local governments. After more than a decade of combat a royalist officer, Agustín Iturbide, brought together royalist forces and rebels to form a coalition that rejected Spanish rule. This chapter concludes by considering the role of various social groups during the revolt, the economic impact of the independence struggle, and U.S. policy toward Spanish American rebellion.

EARLY NINETEENTH-CENTURY GRIEVANCES

Throughout most of the colonial period, the vast majority of New Spain’s residents remained loyal to the king, just as, being good Catholics, they were loyal to the pope. Gradually, however, colonists became disenchanted with royal administration. Eventually after grievances accumulated most politically aware Mexicans welcomed a clean break with both royal administration and the monarchy.

In most instances, inefficiency, incapacity, and corruption permitted early eighteenth-century creoles considerable flexibility, autonomy, and even a modicum of self-government. The 1786 creation of intendancies directly targeted local officials and their illegal, but widely tolerated, commercial monopolies. The Bourbon state regarded the ending of creole participation and its corollary, government by compromise, as necessary steps toward control and revival. Residents of New Spain perceived these same measures as the issuance of non-negotiable demands from an imperial state. As historian John Lynch commented, “To creoles this was not reform.”

In the short term royal agents successfully fulfilled their goal of increasing colonial revenue. The Bourbons increased the alcabala from 4 percent to 6 percent, which produced a sharp increase in the price of food and household goods. New taxes were placed on various commodities such as grains, cattle, and distilled beverages (aguardiente). Tax collection increased from an average of 6.5 million pesos annually during the 1760s to 17.7 million pesos in the 1790s as growth in mining, commerce, and the internal market enlarged the tax base. Between 1779 and 1820, the cost of trade restrictions and taxes equalled 7.2 percent of Mexico’s income. In 1775, British colonialism only cost its North American colonies 0.3 percent of their income.

Contemporary observers felt that taxes had exceeded the prudent level. Humboldt reported that New Spain contributed ten times as much revenue to Spain, on a per capita basis, as did India to Britain. These taxes fell upon all social groups. As Lynch noted, by increasing monetary demands on New Spain, the Bourbon’s “gained a revenue and lost an empire.”

Creoles resented economic restrictions, such as the prohibition on producing paper, which protected Spanish producers. Except in colonies such as Cuba and Venezuela, which could produce export crops, landowners received little benefit from Bourbon trade reforms. Lowered trade barriers hurt Mexico’s relatively unsophisticated manufacturers. By 1810, European imports were competing with textiles produced in Querétaro and Puebla. Finally, Spanish trade policy failed to recognize that Mexican mining, agriculture, and commerce had few economically rational links to Spain. The mother country could not supply the American market nor could it absorb goods produced in the New World.

Economic growth under the Bourbons did not translate into improved living standards for the majority of Mexicans. Higher taxes and the concentration of income left little for the majority. Cash crops increasingly relegated corn farming to marginal lands, while the population increased from 4.48 million in 1790 to 6.12 million in 1810. Not surprisingly agricultural prices rose 50 percent between 1780 and 1811. Food, housing, and clothing all increased in price more rapidly than wages after the 1780s.

FROM BAD TO WORSE

In the wake of the Napoleonic invasion of the Iberian Peninsula, the Spanish and Portuguese territories of the New World would be forced to come to grips with what constitutes legitimate authority in the absence of the monarch.

(John Schwaller, 2011)

Repeated changes in Spanish shipping policy, a result of Spain’s nearly constant wars, added to resentment in the New World. From 1793 to 1795, Spain fought France in a futile attempt to reverse the French Revolution. In addition Spain and England were at war for most of the years from 1796 to 1807. When Spain and Britain were at war, the British fleet attacked ships after they left Veracruz and blockaded Spain’s ports, thus interrupting trade with Spanish America. In 1797, to allow its colonies to export and receive supplies, the Spanish Crown allowed trade with neutral countries, whose ships brought badly needed cigarette paper, mercury, and textiles. Two years later, Spain prohibited such trade, claiming it only benefited Britain. In 1804 war again interrupted shipping, and Spain again permitted trade with neutrals. The legalization of neutral trade resulted in a rapid expansion of U.S. shipping to Spanish America—a harbinger of even greater influence. U.S. ships carried American flour and re-exported British textiles to Mexico.

In 1804, to ease its war-induced financial woes, the Crown ordered that all debts owed to the Mexican Church should be repaid immediately and that the funds collected should be sent to Spain. Bishop-elect Manuel Abad y Queipo of Michoacan estimated that credit extended by the Church totalled 44 million pesos, two-thirds of Mexican capital in active circulation—money used to pay salaries and grow crops. He predicted the withdrawal of this capital would severely damage agriculture, mining, and commerce. Less than a week after the publication of the decree, the Mexico City government declared the measure “totally impractical,” since “it would inevitably bring ruin to these dominions and cause enormous damage to the state.” The Crown’s desperate need for funds caused it to ignore such warnings.

Spanish officials had assumed that the decree, known as the Consolidation Decree, would have an effect comparable to that of a similar 1798 decree issued in Spain, where the Church owned large tracts of property. However, unlike in Spain, where 90 percent of church wealth was invested in real estate and only 10 percent was liquid, in New Spain only 12 percent was invested in real estate, and the rest was liquid. Church loans financed the operations of New Spain’s 200,000 entrepreneurs, only 5 percent of whom operated entirely with their own capital.

The 12 million pesos extracted from Mexico as a result of the Consolidation decree damaged the interests of miners, hacendados, merchants, and artisans who operated on borrowed capital. Many businesses were closed as buildings were seized and sold at auction. Medium-sized and small landowners who could not obtain cash to liquidate debts suffered the most. They were forced to sell their houses, ranchos, and haciendas to repay loans just when others’ sales had cause the price of real estate to decline by half. The decree devastated schools, hospitals, and social welfare institutions, such as orphanages, which had been sustained by income from Church investment. It also embittered the lower clergy, since many of its members lived on interest from chaplaincies and loaned capital. Commenting on the European conflict that motivated the Consolidation Decree, Mexican priest Fray Servando Teresa de Mier lamented: “The war is more cruel for us than for Spain, and is ultimately waged with our money. We simply need to stay neutral to be happy.”

In 1808, Napoleon sent French troops into Spain to further his imperial ambitions. He forced King Fernando VII off the throne, imprisoned him in France, and installed his own brother Joseph as the Spanish monarch.

Spaniards rejected Joseph not only as a foreign usurper but, since he came from revolutionary France, as an atheistic threat to the very foundations of Hispanic society. Soon various groups, or “juntas,” sprang up in Spain to oppose Napoleon’s forces. They claimed that in the absence of Fernando, whom they continued to recognize, they were the true representatives of the Spanish nation. The dominant junta represented Seville. For a brief period the invasion of Spain united New Spain. Its residents, regardless of their wealth or which side of the Atlantic they had been born on, rallied around the deposed Fernando and declared their opposition to the French occupation of the Mother Country.

To fill the power vacuum in Mexico, a junta central began meeting in Mexico City. Its members included Viceroy José de Iturrigaray, the archbishop, members of the Mexico City government, various other administrators and distinguished persons from other cities. The junta confirmed its support for Iturrigaray and announced that it would only subordinate itself to a junta in Spain that was appointed by Fernando. Since he was a prisoner in France, that was tantamount to saying the junta in Mexico City would manage New Spain’s affairs until such time as the Spanish monarch returned to the throne.

Creoles who convened the Mexico City junta operated on the premise that Mexico was not a colony of Spain, but a kingdom co-equal to Spain under the monarchy. They reasoned that with the monarch absent, the link uniting Spain and New Spain had ceased to exist. They also reasoned that until Fernando’s return, Mexican sovereignty resided in the representatives of the people—the cities, the tribunals, and other major corporations.

Spaniards in Mexico did their best to quash notions that Mexicans might assume sovereignty. On August 27, 1808, the Inquisition declared any theory that sovereignty resided in the corporations or the people at large to be heretical. The audiencia claimed that the declarations by members of the Mexico City municipal government that sovereignty was based on a pact between the governed and the monarch only served as a smokescreen for their desired independence.

Many Spanish-born people believed that Iturrigaray’s cooperation with the junta indicated that he sought to separate Mexico from Spain. No evidence has been found to support that assumption, but that did not prevent Spaniards from acting on it.

Shortly after midnight on September 16, 1808, wealthy Spanish hacendado Gabriel de Yermo assembled an armed force numbering roughly 300. It was largely composed of immigrant Spanish merchants who swept into the viceregal palace and arrested Iturrigaray. The coup enjoyed the support of the military, the archbishop of Mexico, consulado members, miners, hacendados, representatives of the Inquisition, and justices of the audiencia. The plotters also imprisoned the leading figures in the municipal government. The audiencia then appointed seventy-seven-year-old Field Marshal Pedro Garibay as viceroy and sent Iturrigaray back to Spain to face trial for treason.

Garibay immediately recognized the junta in Seville as the legitimate ruler of Mexico and began sending it Mexican silver. In doing this, he made a giant intellectual leap. Creoles had asserted that if the monarch was absent, Mexicans were Mexico’s sovereign. Garibay’s recognition of the Seville junta, however, asserted that the absence of the monarch justified a self-proclaimed ruling junta of Spaniards becoming Mexico’s sovereign.

In the short run, the coup was a success, since it halted the slide toward creole autonomy. However, in the long run the coup destroyed what survived concerning the mystique surrounding power. It became even clearer that naked force, not the divine right of kings, formed the basis of Spanish rule.

THE HIDALGO REVOLT, 1810–1811

In May 1810, priest, public intellectual, and eventually bishop-elect of Michoacán Manuel Abad y Queipo predicted a colonial revolt due to colonial grievances and the “electric” example of the French Revolution. He urged the Crown to appoint an enlightened military man as viceroy and that competent military officers, field cannons, cannon balls, and grapeshot also be sent to Mexico.

The warning indicated Abad y Queipo’s prescience since, unbeknownst to him, residents of the Bajío region northwest of Mexico City were plotting a revolt against the government. Before 1500, the Bajío, a vast high plain in what is now the state of Guanajuato, was a little settled basin—a frontier between Mesoamerica and the indigenous people of the North American interior. By 1800, the Bajío had become one of the most prosperous and densely populated areas in Mexico. Its population, which contained few Spaniards or traditional Indian villages, was more socially mobile than the Mexican population as a whole. Its mixed economy, based on mining, herding, manufacturing, farming, and artisan production, was the most thoroughly commercial in New Spain. Numerous small farmers had been forced onto marginal lands by commercial estates. The 1808–10 draught further impoverished them.

The 1810 conspirators met regularly in Querétaro, 125 miles northwest of Mexico City, under the guise of attending a literary society. The most distinguished conspirator was Miguel Domínguez, from an elite local family, who served as the corregidor of Querétaro. Other conspirators included his wife, Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez (“La Corregidora”), and various lawyers, military officers, and commercial and religious figures. Neither members of the central elite nor the poor joined the Querétaro conspiracy. The conspirators hoped to strike a quick blow against the Spanish, that is, do to the Spanish what they had done to Iturrigaray. The planned uprising was initially set for December.

Miguel Hidalgo, one of the conspirators, served as the priest of Dolores, a Bajío town of 15,000. Hidalgo, the son of a hacienda manager, read prohibited books and loved wine, dance, and other worldly pleasures. He served as a one-man community development project promoting tanning, carpentry, beekeeping, the weaving of wool, and the production of silk, pottery, tiles, and wine. In addition he produced theater, sometimes his own translations of French works. In 1804 after the recall of Church loans, the Crown temporarily seized and rented out Hidalgo’s small hacienda to generate income to repay the 7,000 pesos he owed.

Spanish authorities received a report concerning the plot and sent officials to arrest the conspirators. Upon learning that the Spanish had begun arresting the plotters, Hidalgo and fellow conspirator Ignacio Allende decided to launch the rebellion immediately. On the morning of September 16, 1810, he issued his famous Grito de Dolores (Cry of Dolores), which set Mexico into rebellion. There are almost as many versions of what he said as there are historians. Most likely the Grito included some or all of the following, “Long Live Fernando VII! Long Live America! Long Live Religion!” and “Death to the Bad Government!” For a significant period after the Grito it was left unsaid if the rebellion sought a clean break with S...