![]()

Chapter 1

Arabia

The Cradle of Islam

Geography

Figure 1.1 Arabian Desert Landscape

The Arabian Peninsula is known in Arabic as jazírat al-‘árab, literally “the island of the Arabs.” It has the shape of a rectangle spanning 1,200 by 900 miles at its extreme measurements. Its territory occupies a little over one million square miles. The Peninsula is separated from the neighboring world by natural barriers: water on three sides (Persian Gulf, Arabian Sea, Indian Ocean, and Red Sea) and the Syrian Desert on the fourth. The land consists of barren deserts, mountains and plateaus (especially in the west), and steppes. The Peninsula’s southernmost part is affected by the Indian Ocean’s monsoons that bring in a limited amount of rainfall. This area and the mountainous areas of North Yemen receive enough rainfall to allow local populations to grow wheat, millet, sorghum, and palm trees. The sandy desert, called al-Rub‘ al-Khali (the “Empty Place”), in the southeast and the Nufud desert in the north have almost no water (see Figure 1.1). The principal centers of Islam, Mecca and Medina, are located in the rugged, inhospitable area in the central western part of the Arabian Peninsula known as the Hijáz. As in the rest of Arabia, rains in the Hijáz are very rare, but when they come they may bring devastating flash floods that leave widespread destruction in their wake. After an abundant rainfall, the water that was not used for irrigation by the local population is stored in specially built reservoirs or in water holes. Amidst this barren, inhospitable terrain, we find a small number of oases with springs and wells, where agriculture is possible. Yáthrib, later to be renamed as Medina, the “City [of the Prophet],” was one such agricultural oasis. Mecca, the native town of the founder of Islam, had no major source of water and had to sustain itself by caravan trade and proceeds from the annual pilgrimage to its shrines.

The Arabs

The main population of Arabia is Arabs, from the Hebrew for “steppe” or “desert”—hence, “steppe/desert (people).” According to the Bible, the Arabs descend from Noah’s eldest son Shem (Sem). Together with Phoenicians, Arameans, and Jews, they form a separate linguistic group known as “Semitic,” that is, the descendants of Shem/Sem. Arabs trace their genealogy back to Ishmael (Arab., Isma‘il), son of Abraham (Ibrahim) by his slave girl Hagar. Hence their Latin nickname Hagareni (from the Greek Hagarenoi). In medieval Europe, they were also known as “Saracens”—a word of obscure provenance that was also borrowed by Latin authors from Greeks.

The Arabs are divided into two major groups: Yamani, residing in the south of the Arabian Peninsula, and Mudari, who occupied its northern part. Before Islam, the Yamani southerners spoke Sabaean (South Semitic) and the Mudari northerners various dialects of Arabic. Southern Arabia had a developed agriculture that sustained a relatively sophisticated civilization known as Sabaean or Himyarite. It was represented by several kingdoms that shared a common religious culture and engaged in both trade and war with one another. The well-being of this civilization, which stood apart from the predominantly nomadic and seminomadic tribal culture of northern and central Arabia, rested on agricultural produce (dates, wheat, and millet) and long-distance trade in frankincense, myrrh, and other aromatic gum resins. South Arabian caravan traders sold their goods to their imperial neighbors in the north, the Byzantines, and the Persians. The rest of the Arabian population also traded, albeit in less valuable items such as dates and animal skins. It has been argued that they may have also exported silver and gold extracted locally.1 The inhabitants of South Arabia served as intermediaries in the trade between the Mediterranean world in the West and the Indian Ocean in the East. Somewhat paradoxically, in Latin sources this barren and inhospitable region was often referred to as Arabia Felix (“Happy Arabia”). This name seems to have been based on the belief, among the Greek and Latin populations of the Mediterranean basin, that its inhabitants possessed an enormous wealth that they had acquired through their trade in the precious aromatic substances previously enumerated. The developed agriculture of South Arabia was supported by complex irrigation systems of which the famous Marib Dam, located in present-day Yemen, was definitely the most spectacular example. The dam was breached around 535, never to be restored. Its destruction symbolized the progressive decline of the settled culture of the south vis-à-vis the warlike, nomadic, and seminomadic tribes of central Arabia. The exact reasons for the collapse of the South Arabian kingdoms are not quite clear. It is occasionally attributed to climatic factors (e.g., the progressive desiccation of the area), which allegedly forced its settled population to give up their agricultural pursuits and revert to nomadism and cattle herding. Some other cataclysms are also cited, such as the gradual but inexorable expansion into the area of the nomadic tribes of central Arabia, which eventually undermined the settled civilization of the South Arabian kingdoms.2

Bedouin Lifestyle

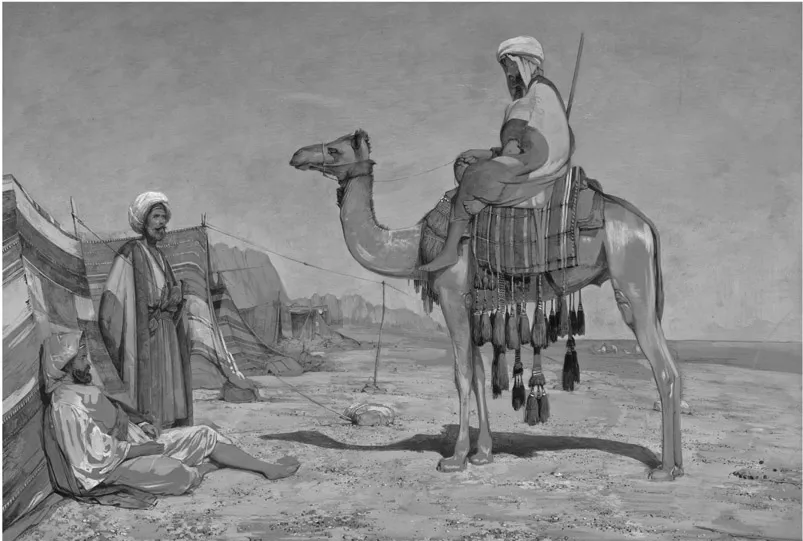

The majority of Arabian nomads were organized in clans, tribes, and tribal confederations. They were and still are often collectively called “Bedouin(s),” from the Arabic badw or bédu (“steppe or desert people”). The Bedouin nomadic and seminomadic lifestyle determined their ethical values, which were different from those of the neighboring Byzantine and Sasanian Empires, which were settled agrarian societies. Life in the desert was a constant struggle for survival with no state institution or central authority to regulate and protect it (see Figure 1.2). Since individual Bedouins simply could not survive on their own, they had to rely on kinsfolk for protection. All members of the kinship group derived their descent from one and the same ancestor, which made for their strong sense of loyalty to one another, especially in time of adversity.3 Another vivid characteristic feature of Bedouin life was hospitality, which could occasionally be excessive or even ruinous for the hosts. A story has it that a renowned tribal poet felt obligated to slaughter his family’s camels to entertain unexpected visitors4—an act that, in our time, would be similar to someone dismantling his family cars and selling their parts in order to feed his guests. Such gestures, costly as they may have been for the host, were essential for him to command respect among his fellow Arabs. Alongside loyalty to one’s kin, the lack of state and legal structures encouraged the development in the Bedouin milieu of a cult of fierce individualism, personal valor, and prowess. This, in turn, encouraged Bedouins to test their mettle by raiding neighbors’ camps and flocks. In addition to demonstrating their personal bravery, raiding helped the Bedouins to supplement their meager livelihood.

Figure 1.2 A Bedouin Encampment, Dating Between 1841 and 1851

Bedouin clans and tribes were characterized by a very high degree of mobility. They journeyed long distances on camels in search of pastures and water holes for their livestock, mostly goats and sheep. Their diet consisted of milk, dates, camel flesh; wheat or millet were usually purchased from the settled populations of Arabian oases. Nomadic Bedouins resided in tents made of camel or goat hair. Bedouin dependence on the camel is captured in an oft cited adage: “The Bedouin is the parasite of the camel.” Crude and ungenerous as this statement may sound, it is impossible to deny that it was the domestication of the camel that made the Bedouin lifestyle possible at all, as it helped human beings to inhabit such an inhospitable and rugged environment as the Arabian deserts.5 The mobility of the Bedouin tribes could give them a temporary advantage in warfare against their sedentary and agriculturist neighbors, who had large armies that were not always easy to mobilize and deploy.

Social Structures

A typical tribe consisted of the chief (shaykh, literally “elder”) and his family (a tribal nobility of sorts), a number of other free families, client clans not related by blood, and slaves. The dire conditions of life in the desert made for a strong “democratic” spirit among its inhabitants whose behavior was characterized by self-reliance, independence, tenacity, and endurance. Tribesmen resented any authority or subordination and treated their shaykh as first among equals. They expected him to consult them on any issues pertaining to the tribe’s or clan’s fortunes. This lack of social hierarchy stood in sharp contrast to the organization of the neighboring Byzantine (Greek) and Sasanian (Persian) Empires, which had an elaborate hierarchy of social classes or estates, namely, the emperor and his court, the military landowning aristocracy, the priests/clergy, the craftsmen and merchants, and, at the very bottom of the social pyramid, the peasants and slaves. Whereas the populations of the empires were subject to elaborate legal codes, in Arabian society blood ties substituted for law. Kinship was the primary mark of citizenship and the entitlement to protection by relatives. The Bedouins took great pride in their lineage and eulogized their ancestors in spirited poetry, which was recited and transmitted orally. Although the inhabitants of central and northern Arabia lived in oases and towns as well as in the desert, there was no clear-cut boundary between the Bedouin of the desert and the dweller of an Arabian urban center. They often intermingled during annual fairs and intermarried among themselves, thereby forging and reinforcing alliances between semisettled and seminomadic groups. During such Arabian fairs, not only material goods exchanged hands but also cultural commodities, especially poetry, witticisms, and stories. In short, tribal ties among settled populations of Arabia were almost as strong as they were among the nomadic Bedouins.

Raiding and Warfare

In the absence of a stable source of livelihood and faced with a scarcity of food and other necessities, the Bedouin, as mentioned, occasionally resorted to raiding and robbery. Raiding neighboring tribes for booty and captives was a common feature of life in Arabia before Islam. Raids frequently resulted in blood feuds between clans and tribes that lasted for decades. Feats of glory and perseverance exhibited by individual tribal warriors and tribes as a whole were glorified in the epic narratives called the “Days of the Arabs.” They recounted details of tribal conflicts and eulogized fallen and surviving heroes. Apart from the epic tales, poetry in particular was the supreme cultural expression of the harsh experiences and vicissitudes of tribal life. It is not accidental that poetry is often called the “register of the Arabs.” Composed in a special poetic language that was distinct from the vernacular dialects of various Bedouin tribes, it was understood and appreciated by all of them.6 Poets were held in high regard for their poetic skills. As in the “Days of the Arabs,” poetic compositions glorified feats of bravery and bemoaned the death of heroes. Poets exalted the martial and moral virtues (especially generosity) of their tribe or clan, while ridiculing the depravity and cowardice of its rivals. As spokesmen and advocates for their tribes, poets enjoyed a special status among their kin. In general, oratory—the art of eloquent speech—was highly valued by all Arabs. Moreover, they believed that words possessed magical qualities: They could bring fortune and misfortune and even hurt like arrows or other weapons. Common were poetic competitions between poets representing different tribes that took place during annual fairs in towns and oases. Each successful poem delivered at such gathering of tribes was quickly memorized and carried across Arabia by professional “rhapsodes” (Arab. ruwa; sing. rawi), that is, transmitters and performers of oral poetry. One can thus say that poetry was the common cultural glue that held together the fractious Arabian tribes and that instilled in them a sense of common ethnic identity above and beyond narrow tribal and clannish loyalties and peculiarities. Thanks to their poetry and epic tales, as well as the similar physical conditions of their existence, Arabs shared a common world outlook as well as a common code of honorable behavior.

Mecca: A Trade Hub

Northern and central Arabia did not benefit from the rain-bringing monsoons that made agriculture possible in the southern areas of the Peninsula. Therefore, in addition to cattle herding, its inhabitants had to rely on either brigandage or trade to secure their livelihood. In the north, the major trade hub was Palmyra (in present-day Syria), while in west-central Arabia (the Hijáz), commercial activities were centered on the town of Mecca. Around the year 400, Mecca became home to the Arab tribe named Quraysh. Muhammad, the future prophet of Islam, was a member of the Hashim clan of that tribe. While the majority of the Quraysh were nominally town dwellers, they nevertheless retained their tribal organization and ethos, which they shared...