![]()

1 Background to Second Language Acquisition Research and Language Teaching

Language is at the centre of human life. We use it to express our love or our hates, to achieve our goals and further our careers, to gain artistic satisfaction or simple pleasure, to pray or to blaspheme. Through language we plan our lives and remember our past; we exchange ideas and experiences; we form our social and individual identities. Language is the most unique thing about human beings. As the Roman orator Cicero said in 55BC, ‘The one thing in which we are especially superior to beasts is that we speak to each other’.

Some people are able to do some or all of this in more than one language. Knowing another language may mean: getting a job; a chance to get educated; the ability to take a fuller part in the life of one’s own country or the opportunity to emigrate to another; an expansion of one’s literary and cultural horizons; the expression of one’s political opinions or religious beliefs; the chance to talk to people on a foreign holiday. A second language affects people’s careers and possible futures, their lives and their very identities. In a world where more people probably speak two languages than one, the acquisition and use of second languages are vital to the everyday lives of millions; monolinguals are nowadays almost an endangered species. Helping people acquire second languages more effectively is an important task for the twenty-first century.

1.1. The Scope of This Book

The main aim of this book is to communicate to language teachers some ideas about how people acquire second languages that come from the discipline of second language acquisition (SLA) research. It is not a guide to SLA research methodology itself or to the merits and failings of particular SLA research techniques, which are covered in books such as Research Methods in Second Language Acquisition: A Practical Guide (Mackey and Gass, 2011) and Second Language Learning Theories (Mitchell, Myles and Marsden, 2012). Nor is it a guide to the many methods and techniques of language teaching, only to some of those that connect with SLA research. Indeed SLA research is only one of the many areas that language teachers need to look at when deciding what to do in their classrooms. The book is intended for language teachers and trainee teachers rather than researchers. While it tries not to take sides in reporting the various issues, inevitably the bias towards the multi-competence perspective I have been involved with for some time is hard to conceal.

Much of the discussion concerns the L2 learning and teaching of English, mainly because this is the chief language that has been investigated in SLA research. English is, however, used here as a source of examples rather than being the subject matter itself. Other modern languages are discussed when appropriate. The English language is unique in being the only language that can be used almost anywhere on the globe between people who are non-native speakers, what De Swaan (2001) calls the one and only hypercentral language; hence conclusions about language acquisition based on English may not necessarily apply to other languages. Most sections of each chapter start with focusing questions, a display defining keywords and an explanation of some of the language background, and end with discussion topics, further reading and glossaries of technical terms.

Contact with the language teaching classroom is maintained in this book chiefly through the discussion of published coursebooks and syllabuses, usually for teaching English. Even if good teachers use books only as a jumping-off point, they can provide a window into many classrooms. The books and syllabuses cited come from countries ranging from Israel to Japan to Cuba, though inevitably the bias is towards coursebooks published in England for reasons of accessibility. Since many modern language teaching coursebooks are depressingly similar in orientation, the examples of less familiar approaches have often been taken from older coursebooks. Coursebooks will usually be cited by their titles as this is how teachers usually refer to them; a list is provided at the end of this book.

This book talks about only a fraction of the SLA research on a given topic, often presenting only one or two of the possible approaches. It concentrates on those based on ideas about language, i.e. applied linguistics, rather than those coming from psychology or education. Yet it nevertheless covers more areas of SLA research than most books that link SLA research to language teaching, for example taking in pronunciation, vocabulary and writing among others, not just grammar. It uses ideas from the wealth of research produced in the past twenty years or so rather than just the most recent. Sometimes it has to go beyond the strict borders of SLA research itself to include such topics as the position of English in the world and the power of native speakers over their language.

1.2. Common Assumptions of Language Teaching

Focusing Question

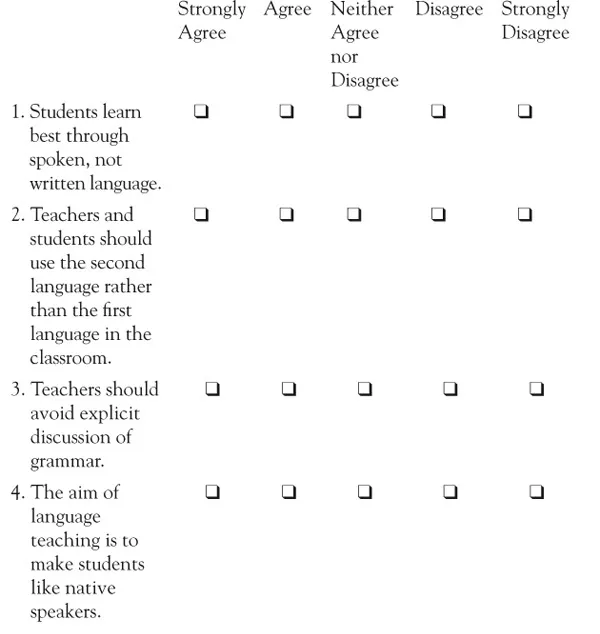

- Answer the questionnaire in Box 1.1 to find out your assumptions about language teaching.

Keywords

- first language: chronologically the first language that a child learns.

- second language: ‘A language acquired by a person in addition to his mother tongue’ (UNESCO, 1953).

- native speaker: a person who still speaks the language they learnt in childhood, often thought of as monolingual.

- Glosses on teaching methods are provided at the end of this chapter.

During the last quarter of the nineteenth century, a revolution took place that affected much of the language teaching used in the twentieth century. The revolt was primarily against the stultifying methods of grammatical explanation and translation of texts which were then popular. (In this chapter we will use ‘method’ in the traditional way to describe a particular way of teaching with its own techniques and tasks; Chapter 11 uses the more general term ‘style’.) In its place the great pioneers of the new language teaching such as Henry Sweet and Otto Jespersen emphasised the spoken language and the naturalness of language learning and insisted on the importance of using the second language in the classroom rather than the first (Howatt, 2004). These beliefs are largely still with us today, either explicitly instilled into teachers or just taken for granted. The questionnaire in Box 1.1 tests the extent to which the reader actually believes in four of these common assumptions.

Box 1.1 Assumptions of Language Teaching

Tick the extent to which you agree or disagree with these assumptions

If you agreed with most of the above statements, then you share the common assumptions of teachers over the past 130 years. Let us spell them out in more detail.

Assumption 1. The Basis for Teaching Is the Spoken, Not the Written Language

One of the keynotes of the nineteenth century revolution in language teaching was the emphasis on the spoken language, partly because many of its advocates were phoneticians. The English curriculum in Cuba for example insists on ‘The principle of the primacy of spoken language’ (Cuban Ministry of Education, 1999). The teaching methods within which speech was most dominant were the audiolingual and audiovisual methods, which presented spoken language from tape before the students saw the written form. Later methods have continued to emphasise the spoken language. Communication in the communicative method is usually through speech rather than writing. The Total Physical Response (TPR) method uses spoken, not written, commands and storytelling, not story reading. Even in the task-based learning approach, Ellis (2003, p. 6) points out ‘The literature on tasks, both research-based or pedagogic, assumes that tasks are directed at oral skills, particularly speaking’. The amount of teaching time that teachers pay to pronunciation far outweighs that given to spelling.

The importance of speech has been reinforced by those linguists who claim that speech is the primary form of language and that writing depends on speech. Few teaching methods in the twentieth century saw speech and writing as being equally important, certainly at the early stages. The problem with this assumption is that written language has distinct characteristics of its own which are not just pale reflections of the spoken language, as we see in Chapter 5. To quote Michael Halliday (Halliday and Mattheisen, 2013, p. 7), ‘writing is not the representation of speech sound’: it is a parallel way of expressing meaning with its own grammar, vocabulary and conventions. Vital as the spoken language may be, it should not divert attention from those aspects of writing that are crucial for students. Spelling mistakes for instance probably count more against an L2 user in everyday life than a foreign accent.

Assumption 2. Teachers and Students Should Use the Second Language Rather than the First Language in the Classroom

The emphasis on the second language in the classroom was also part of the revolt against the older methods by the late nineteenth century methodologists, most famously through the Direct Method and the Berlitz Method with their rejection of translation as a teaching technique. The use of the first language in the classroom is still seen as undesirable whether in England—‘The natural use of the target language for virtually all communication is a sure sign of a good modern language course’ (DES, 1990, p. 58)—or in Japan—‘In principle English should be selected for foreign language activities’ (MEXT, 2011). This advice is echoed in almost every teaching manual: ‘the need to have them practicing English (rather than their own language) remains paramount’ (Harmer, 2007, p. 129). One reason sometimes put forward for avoiding the first language is that children learning their first language do not have a second language available, which is irrelevant in itself—infants don’t play golf but we teach it to adults. Another argument is that the students should keep the two languages separate in their minds rather than linking them together; this adopts a compartmentalised view of languages in the same mind, called coordinate bilingualism, not supported by SLA research, which mostly stresses the continual interplay between the two languages, as we see everywhere in this book. Nevertheless many English classes justifiably avoid the first language for practical reasons, whether because students have different first languages or because a native speaker teacher does not know the students’ first language. This topic is developed further in Chapter 8.

Assumption 3. Teachers Should Avoid Explicit Discussion of Grammar

The ban on teaching grammar to students explicitly also formed part of the rejection of the old-style methods. Grammar could be practised through drills or incorporated within communicative exercises but should not be explained to students. While grammatical rules can be demonstrated through substitution tables or through situational cues, actual rules should not be mentioned. The old arguments against grammatical explanation were both the question of conscious understanding—knowing some aspect of language consciously is no guarantee that you can use it in speech—and the processing time involved—speaking by consciously using all the grammatical rules means each sentence may take several minutes to produce, as those of us who learnt Latin by this method will bear witness. Chapter 2 describes how grammar has recently made a minor comeback.

Assumption 4. The Aim of Language Teaching Is to Make Students Like Native Speakers

One of the assumptions that has been taken for granted is that the role model for language students is the native speaker. Virtually all teachers, students and bilinguals have measured success by how closely a learner gets to a native speaker, in grammar, vocabulary and particularly pronunciation. David Stern (1983, p. 341) puts it clearly: ‘The native speaker’s “competence” or “proficiency” or “knowledge of the language” is a necessary point of reference for the second language proficiency concept used in language teaching’. Coursebooks are overwhelmingly based on native language speakers; examinations compare students with native speakers. Passing for a native is the ultimate test of success. Like all the best assumptions, people so take this for granted that they can be mortally offended if it is brought out into the open and they are asked ‘Why do you want to be a native speaker in any case?’ No other possibility than the native speaker can be entertained.

Many of these background assumptions are questioned by SLA research and have sometimes led to undesirable consequences. Assumption 1 that students learn best through spoken language leads to undervaluing the features specific to written language, as we see in Chapter 5. Assumption 2 that the L1 should be minimised in the classroom goes against the integrity of the L2 user’s mind, to be discussed later in this chapter and in Chapter 8. Assumption 3 that grammar should not be taught explicitly implies a particular model of grammar and of learning, rather than the many alternatives shown in Chapter 2. The native speaker assumption 4 has come under increasing attack in recent years, as described in Chapter 8, on the grounds that a native speaker goal is not appropriate in all circumstances and that it is unattainable by the vast majority of students. Even if these 130-year-old assumptions are usually unstated, they continue to be part of the basis of language teaching however the winds of fashion may blow.

1.3. What Is Second Language Acquisition Research?

Focusing Questions

- Do you know anybody who is good at languages? Why do you think this is so?

- Do you think that everybody learns a second language in roughly the same way?

Keywords

- Contrastive Analysis (CA): this research method compared the descriptions of two languages in grammar or pronunciation to discover the differences between them; these were then seen as difficulties for the students to overcome. Note the abbreviation CA is also often used as well both for Conversation Analysis and for the Communicative Approach to language teaching.

- Error Analysis (EA): this research method studied the language produced by L2 learners to establish its peculiarities, which it tried to explain in terms of the first language and other sources.

As this book is based on SLA research, the obvious opening question is ‘What is SLA research?’ People have been interested in the acquisition of second languages since at least the Ancient Greeks, but the discipline itself only came into being about 1970, gathering together language teachers, psychologists and linguists. Its roots were in 1950s studies of Contrastive Analysis which compared the first and second lang...