![]()

Article 30

A Qualitative Analysis of the Bullying Prevention and Intervention Recommendations of Students in Grades 5 to 8

CHARLES E. CUNNINGHAM

McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

JENNA RATCLIFFE

McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

LESLEY J. CUNNINGHAM

Hamilton-Wentworth District School Board, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

TRACY VAILLANCOURT

McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

ABSTRACT. Focus groups explored the bullying prevention suggestions of 62 Grade 5 to 8 students. Discussions were transcribed and analyzed thematically. Students advocated a comprehensive approach including uniforms, increased supervision, playground activities, group restructuring to prevent social isolation, influential presenters, prevention skills training, solution-focused posters, and meaningful consequences. In addition, students suggested that parents should improve relationships with their children, respond to aggression, limit exposure to media violence, and support school-based discipline. The failure to respond effectively to students who bully in defiance of antibullying presentations, and who retaliate when reported or disciplined, undermines prevention programs by reducing the willingness of bystanders to intervene or report bullying and influencing the attitudes of younger pupils. The approach advocated by students is supported by meta-analyses of the effective components of bullying prevention trials.

From Journal of School Violence, 9, 321-338. Copyright © 2010 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. Reprinted with permission.

Bullying poses risks to the health and emotional well-being of both victims and perpetrators (Arseneault, Bowes, & Shakoor, 2009). Although reviews suggest that promising approaches to bullying prevention are emerging, outcomes are often disappointing (Farrington & Ttofi, 2009). A meta-analysis of 16 bullying prevention trials, for example, concluded that although programs have a modest effect on knowledge, attitudes, and self-perceptions, they exert little effect on bullying behavior (Merrell, Gueldner, Ross, & Isava, 2008). Despite progress in understanding the prevalence, correlates, and longitudinal trajectories of bullying, there is a need to improve prevention and intervention programs.

A growing number of investigators have concluded that the design of more effective bullying prevention programs should be informed by students (Booren & Handy, 2009; Camodeca & Goossens, 2005). In comparison to teachers, students know more about peers who bully, the conditions under which bullying occurs, students who are victimized, and the response of their peers to prevention programs (Bradshaw & Sawyer, 2007). Students could, therefore, provide a unique perspective on the components of prevention programs that work, factors limiting the impact of these programs, and modifications that might improve outcomes.

Previous studies have asked students to indicate how they would respond to bullying (Camodeca & Goossens, 2005; Salmivalli, Karhunen, & Lagerspetz, 1998) or to rate the effectiveness of different approaches to prevention (Booren & Handy, 2009; Peterson & Rigby, 1999). When surveys provide an opportunity to record their comments, students suggest that schools prevent bullying by increasing supervision (Varjas et al., 2008), intervening earlier (Varjas et al., 2008), or using effective consequences (Peterson & Rigby, 1999). This study builds on previous work by examining the bullying prevention suggestions of students in Grades 5 to 8, a time when bullying peaks (Vaillancourt et al., 2008) and students lose confidence in the ability of their teachers to solve this problem (Bradshaw & Sawyer, 2007). Qualitative methods (e.g., focus groups) allowed the study to focus on prevention options of relevance to students, explore design recommendations in depth, compare the suggestions of boys and girls, identify factors influencing the effectiveness of existing programs, and generate a rich narrative supporting inductive theory development and the interpretation of findings from the project's quantitative stage.

Method

Participants

This study was approved by the university/hospital Research Ethics Board and the public and Catholic school systems that participated. Using a stratified purposeful sampling strategy (Patton, 2002), the project was introduced to Grade 5 to 8 classes (see Table 1) at coeducational publicly funded schools randomly selected from areas representing the diverse demographics of an urban and suburban Canadian industrial community of 505,000 residents. With one junior kindergarten (age 4) to Grade 5 exception, schools were junior kindergarten to Grade 8. A project description and consent form was sent to parents, consents were returned, and 67 students were randomly selected (39 girls and 28 boys); 62 students were present, signed assents, and participated. One focus group was conducted in each of five schools, and two groups were conducted in three schools.

Procedures

Small group discussions were adopted as a familiar format allowing students to respond to the suggestions of their peers. Assuming boys and girls have different perspectives and are less inhibited in same sex groups (Nabors, Ramos, & Weist, 2001), four boy groups, six girl groups, and a mixed group (to determine whether new themes would emerge) were conducted. Using a structured interview guide, a school social worker, with the support of a research assistant, described the project and obtained assent. Students were assured they would not be named nor asked about their personal bullying experiences. Facilitators conducted introductions, defined bullying (Vaillancourt et al., 2008), and asked (in their own words), "Can anyone give us an example of something that schools are doing to help stop bullying?" Facilitators flexibly encouraged discussion with the following prompts: "Could you tell us a little more about this example?",' "Could other students tell me about this example?"; "Do you think this reduces bullying at school?"; "What do other students think?"; and "Why do you think this reduces bullying at school?"

Next, the facilitator asked, "Does anyone have a suggestion about what else might reduce bullying at school?" Discussion was encouraged with the following prompts: "What do others think of this suggestion?"; "Do others think this would reduce bullying at school?"; and "Why do you think this would reduce bullying at school?"

Reliability coding showed that 95% of 7 key interview guide components were present. Data collection was discontinued when a review of the final focus group's transcript revealed no new themes (Patton, 2002).

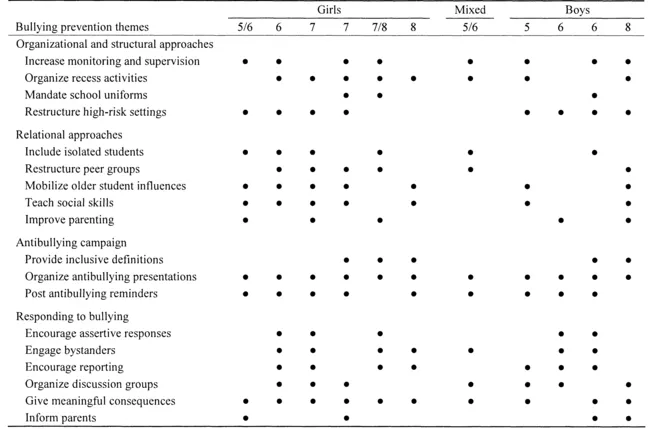

Table 1

Bullying Prevention Themes Emerging From the Study's 11 Focus Groups

Data Analysis

Audio recordings were transcribed and identifiers were removed. The lead investigator, a research assistant, and a school social worker reviewed transcripts and developed preliminary thematic categories (Patton, 2002). Investigators noted suppositions and biases (e.g., two investigators developed and evaluated peer mediation programs) and attempted to limit their influence (Patton, 2002). To reduce potential gender biases, for example, male and female investigators participated at all stages of the data analysis. A researcher without links to the schools used NVivo-7 to code the transcripts. Next, two investigators with expertise in school-based prevention independently reviewed the transcripts. Table 1 summarizes the grade and sex of the participants in the study's 11 focus groups and the distribution of bullying prevention themes across groups. Initial interobserver agreement on the occurrence of themes in a random sample of three groups was 81%. Discrepancies were resolved via consensus, definitions were revised, and new codes were introduced. Quotations representing recurring themes were selected, and transcripts were searched for supporting and disconfirming examples (Patton, 2002).

Results

Organizational and Structural Approaches to Prevention

Restructure High-Risk Settings. The architecture of schools contributed to bullying problems: "Like for our school, for instance, some of the bullying happens near the portables [portable classrooms] because they're out of sight and there's not really any teachers usually on the grass for duty, they're usually only on the pavement." Bullying could be prevented by restructuring the physical environment, reducing the number of students in high-risk settings, and separating older and younger students: "They should have teachers in the hall not letting the intermediates [Grades 7-8] all just rush out our door and to tell them to go to their own door."

Organize Recess Activities. Because bullying occurs when students are unoccupied, schools could prevent bullying by organizing recess activities: "Bullying usually happens when people need something to do...because a lot of them are bored and they want something fun so they tease little kids"; "Maybe they could put up games, like different games for people to go and play at so the children would be occupied...they really [wouldn't] want to bully; they'd be playing."

Increase Supervision. Playground supervisors are unable to observe many bullying episodes: "They can't see everything that's going on. It's just not possible. There's too much area to cover." Supervisors, moreover, do not pay attention to bullying: "They're too busy talking to each other instead of looking for situations." Indeed, students questioned whether supervisors were motivated to reduce bullying: "They make a big deal about [it] and they don't even care, the teachers." Students who bully surreptitiously or enable bullying by distracting teachers compounded this problem: "But if they know there's a teacher around they would lower their voices so they wouldn't get caught..."; "They send their friends to talk to the teacher to distract them from it so they won't know about it." Increasing supervision in high-risk settings was a recurrent theme: "Have more teachers on duty and spread them out more." Increased supervision could also be accomplished via students: "The people who want to prevent bullying can be like monitors outside to help the kids." Finally, several groups proposed the installation of surveillance cameras: "When the teachers are gone, it's a totally different world for us kids, so if they have cameras, then they can't do it."

Mandate School Uniforms. Because differences in clothing triggered bullying, some participants proposed that schools adopt uniforms: "I think it would definitely reduce bullying because you can't judge what other people are wearing because they're wearing exactly the same thing." Others felt that students would simply exploit differences in the way uniforms were worn:

We always have debates on that because you might be the only person that's wearing shorts, your uniform, and everybody in your class is wearing pants or a skirt and you're the one that gets picked on for the day.

Relational Approaches

Include Isolated Students. Isolated students were perceived to be especially vulnerable to bullying: "Bullying usually happens if you're alone and you have no one to be with; bullies tend to go for a lonesome person." Students and teachers should share responsibility for the inclusion of isolated pupils: "If you see somebody like sitting there, ask them if they want to play with you"; "If teachers see someone get discluded [sz'e] or whatever, they see other people going to help them and bring them into their group." The victimization of new students could be reduced by integrating them into existing peer groups: "If there are any new kids, like somebody from the class could go and greet them and maybe include them in a game instead of leaving them alone so...he or she could easily be a target for a bully." Although relationships afforded some protection, students with friends were also at risk:

Friends are the mam cause of bullying...because you tell them everything when you think they're your best friend and then if.. .they turn around on your back, then they can go tell everyb...