eBook - ePub

The Making of a Chinese City

History and Historiography in Harbin

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The history of Harbin, ruled by the Russians, by an international coalition of allied powers, by Chinese warlords, by the Soviet Union and finally by the Chinese Communists - all in the course of 100 years - is presented here as an example of Chinese local-history writing.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Making of a Chinese City by Soren Clausen,Stig Thogersen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Public Affairs & Administration. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

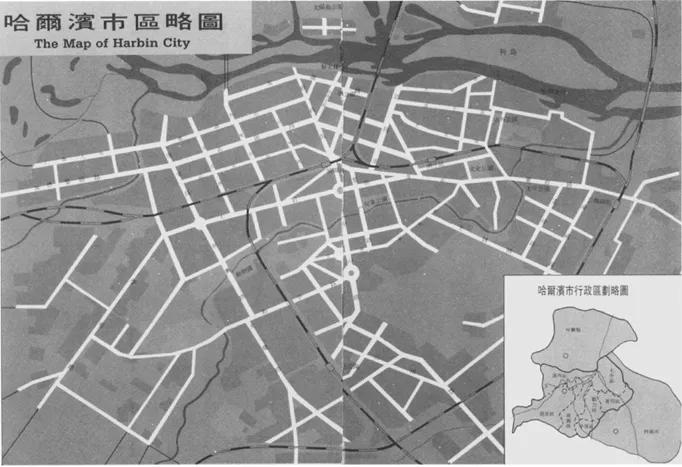

Map 1. Old Harbin. From Hansine Schmidt and Chr. Madsen, Harbin. Den store, nye By i det fjerne Østen og Missionsarbejdets Begyndelse dér [Harbin, the new big city in the Far East and the starting-up of missionary work there] (Copenhagen: DMS, 1939), p. 5.

Map 2. New Harbin. From Harbin Yearbook, 1987.

THE MAKING OF A CHINESE CITY

2

The Era of Russian Influence: 1898–1932

After the arrival of the railway engineers in 1898, Russian influence in Harbin was indisputable and highly visible for several decades. The city was initially run directly by the Russian Chinese Eastern Railway (CER) management, but in the years 1907–17 its status changed to that of an “open city,” with the Russians still playing the leading role. After the 1917 Russian revolution, Harbin remained dominated by its White Russian community for yet another decade (1917–26), while at the same time experiencing growing Soviet influence in the years following the 1924 Sino-Soviet treaty concerning the CER. The gradual dilution of Russian power in Harbin thus followed a complicated course: purely Russian rule gave way to a growing international presence, and after 1917 the Russian factor was itself split into “white” and “red” forces.

Thus things appeared to the European travelers, businessmen, diplomats, and missionaries who visited and reported on Harbin in the first three decades of the twentieth century, as well as to later Western and Russian historians. To the Chinese local historians, however, the crucial factor in Harbin’s changing political and economic landscape during this period is the sinification of the city, the development and maturation of its Chinese population as well as the perennial struggle to re-establish Chinese sovereignty in the area. In the eyes of the contemporary local historians, this process of sinification is best brought out by focusing on the local manifestations of the great upheavals that shaped the Chinese nation during the period in a broad context of early industrialization, the rise of nationalism, and the emergence of communism as a political force.

The “Russian perspective” on early Harbin history thus differs fundamentally from the Chinese historians’ approach. For the purpose of an outline, however, the structure of Harbin’s political and economic history cannot be divorced from the larger political drama of wars and revolutions influencing the history of the Far East.

Direct Russian Rule, 1898–1907

The Struggle over Manchuria

Toward the end of the nineteenth century Manchuria had become the object of a tripartite race for control among China, Russia, and Japan. Far-reaching plans were being drawn up in Russia, where construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway was begun at Vladivostok in 1891. By 1894, survey crews were reporting that technical difficulties could be expected if the railway were routed north of the Amur River as originally planned (Wieczynski 1976, p. 49). The idea of running a line directly through Manchuria in order to save some 340 miles of railway is normally attributed to Count Witte, the highly influential Russian minister of finance from 1892 to 1903. The opportunity to force such a concession from China came with the Chinese defeat in the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95. As part of the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki, China ceded the Liaodong Peninsula in southern Manchuria to Japan, but Russia took the lead in the Three Power Intervention that year, which persuaded Japan to accept retrocession of Liaodong to China. As payment for this service Russia demanded the needed railway concession in North Manchuria. To circumvent Chinese objections to the operation of the railway as a Russian government enterprise, in 1895 Witte set up a “nongovernment” subsidiary company of the Russo-Chinese Bank as a thinly disguised adjunct to the Russian treasury for the purpose of penetrating Manchuria and the whole of North China (Huenemann 1984, pp. 49–50). The contract between this company and China was signed on September 8, 1896. It covered an eighty-year period, after which the railroad would revert to China free of charge. After thirty-six years China would have the option of buying back the railroad at foil payment of the invested capital. Construction work started the year after, and in 1898 Harbin was established as headquarters of the project. The line was put in operation in 1903, but in the meanwhile the teeth of the imperialist powers had been sharpened considerably.

In 1898 Russia forced China by gunboat diplomacy to accept a twenty-five-year Russian lease of Dalian and Port Arthur on the Liaodong Peninsula as well as a new railway concession, this time from Port Arthur to Harbin, creating the southern arm of the T-shaped Manchurian Railway. Russian designs in Manchuria and North China became more candid, and the Boxer Rebellion of 1900, which extended to most places in Manchuria, was followed by Russian intervention and foll-scale occupation of Manchuria by an expeditionary force of about 100,000 men. By November 1900 the region was more or less under Russian military control. After the Boxer Protocol was signed Russia clung to Manchuria, demanding the virtual cessation of the region, but with the Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Alliance of January 1902 Russia was grudgingly forced to withdraw its forces. Russian procrastination in carrying out the evacuation from Manchuria was one of the direct causes of the outbreak of war between Russia and Japan in 1904. After the Russian defeat in 1905, the Russian possessions in the Liaodong area as well as the Port Arthur—Changchun railway link, henceforth known as the South Manchurian Railway (SMR), were surrendered to Japan, which now joined in the struggle for domination of Manchuria as a major player. The area was de facto divided into Russian and Japanese spheres of influence along an east-west line passing through Changchun.

Faced with the danger of losing its ancestral lands in the Northeast entirely, the Qing government employed the two related strategies of frontier management and self-strengthening (Hunt 1973, p. 86f). But the disastrous effects of the 1896 alliance with Russia had demonstrated the limitations of the time-honored method of “using barbarians to control barbarians,” and China observed strict neutrality in the Russo-Japanese War. The cautious approach was rewarded as the Chinese government regained much of its authority in Manchuria after the Russian military evacuation in 1905. As for self-strengthening, the strategy of promoting Chinese migration to Manchuria was further intensified during the 1898–1907 decade.

Harbin and the Chinese Eastern Railway

The Russian buildup in Manchuria during the 1896–1905 period was marred by a lack of overall strategy and purpose; by 1898 Russia had made clear to the other powers her ambitions in Manchuria and indeed in the whole of North China (Huenemann 1984, p. 51), but a strategy for this enterprise was never worked out and the Russian government was deeply divided on the issue. The legal basis for the Russian presence in Harbin reflected this ambiguity. Although Russian domination in young Harbin was a de facto colonial setup, the legal and political foundation of Russian rule in Harbin remained tied to the CER contract of September 1896 (the treaty is reproduced in MacMurray 1921, pp. 74–78). The stipulations of this contract regarding ownership of the railway, composition of the board of directors, military protection of the railway, and taxation and administration of the railway zone turned out to be—from the Russian angle—inadequate to secure undisputed control of Harbin, even when the interpretation of the stipulations was stretched to the very limit. The Chinese authorities never lost their foothold entirely in the struggle to maintain a measure of control in the Harbin area and the railway zone, even though a major Chinese effort to regain the initiative did not materialize until after the Russo-Japanese War.

The city of Harbin took shape in the quagmire of Sino-Russian disputes relating to the interpretation of the CER contract. Certain issues were of particular significance in determining Harbin’s future development:

The Definition of the Railway Zone

Article VI of the contract stipulated that “lands actually necessary for the construction, operation and protection of the line, as also the lands in the vicinity of the line necessary for procuring sand, stone, lime, etc., will be turned over to the Company,” but the contract provided neither clear limitations on the company’s land acquisitions nor a method for resolving conflicts in this regard (MacMurray 1921, p. 76). From the outset the CER company occupied large tracts of land along the route of the railway far in excess of the actual need for railway construction, and even after the completion of the railway, this “zone” was continuously expanded by the company. The more important stations of the railway had large tracts of land set aside for them, with Harbin as the largest, eventually growing to 15,800 acres (Gladeck 1972, p. 43). Bordering this area, however, a Chinese settlement contiguous with Russian-built Harbin grew apace. A host of problems relating to sovereignty, jurisdiction, administration, and so on were inherent in this setup.

Jurisdiction

The problem of jurisdiction in the city of Harbin was compounded by a discrepancy between the Chinese and Russian versions of the relevant section in the CER contract. In the Chinese version of Article VI, the central clause reads: “all the land utilized by the said [CER] Company is to be exempted from land taxation and to be managed by the said company singlehandedly” (you gai gongsi yishou jingli)1 The implication of this version is a businesslike relationship in a context of Chinese sovereignty. In the Russian version, however, the last phrase is taken out to form an independent sentence, and indeed an independent paragraph of Article VI: “The Company will have the absolute and exclusive right of administration of its lands.”2 The difference between these two versions of the contract is crucial, because the ensuing de facto Russian colonization of the railway zone, that is, the entire Russian system of judicial and police authority as well as the structure of municipal administration in ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Studies on Modern China

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- THE MAKING OF A CHINESE CITY

- 1 Genesis: Pre-1898 History

- 2 The Era of Russian Influence: 1898–1932

- 3 Japanese Occupation: 1932–1945

- 4 Socialist Transformation: 1945–1989

- 5 The Harbin Historians

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

- List of Contributors