![]()

Part I

Analysis and assessment

![]()

1 The problem

The outbreak of war

On a summer’s morning late in June 1914, the heir to the throne of the Habsburg monarchy arrived at the Bosnian town of Sarajevo for an official visit. While the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, his wife and his entourage proceeded through the crowded main street of the city in open motorcars, a young man stepped out of the crowd and hurled something at the archduke. A bomb exploded, narrowly missing the archduke but grazing his wife on the cheek, wounding a military member of the entourage and injuring several spectators. The would-be assassin was seized immediately. Franz Ferdinand, against the advice of his aides, insisted that they continue their journey to the town hall, as planned. Here the Austrians endured a fulsome speech by the mayor, saturated with unintentionally ironic references to the loyalty of the Bosnian people and the esteem in which the distinguished visitor was held in the province. The archduke replied by reading from his prepared speech, which was now splattered in blood. When this agony finally ended, Franz Ferdinand insisted that he be permitted to visit the hospital to see one of his aides who had been injured by the exploding bomb. As the party retraced its route along the main street, some confusion occurred which resulted in the archduke’s chauffeur being forced to stop and reverse direction in the middle of the street. Seizing this unexpected opportunity, a second assassin emerged, this time wielding a pistol rather than a bomb; quickly taking aim, he shot Franz Ferdinand in the throat, striking him near the jugular vein; a second shot hit the duchess in the stomach. Within minutes, both the archduke and his wife lay dead. Before the summer was over, this dramatic event would lead to the greatest war Europe had ever known.

Few Europeans at the time anticipated that the murder of the archduke would draw them into a crisis and then into a war. Assassinations were not unknown in Europe – recent victims included kings of Italy, Portugal and Greece, an empress of Austria, a president of France and two premiers of Spain. None of these had produced an international crisis; none had led to armed conflict. Some difficulties were to be expected in the region of Sarajevo, where the day after the assassination Serb shops, businesses, schools and clubs were ransacked and looted; the Austrian government declared a state of martial law. But the events in the Balkans seemed far away not only to the English, but to the French and to the Germans as well. Europe had weathered much more threatening crises in the recent past, and the first few days following the death of the archduke were notable mainly for the absence of any frantic diplomatic activity.

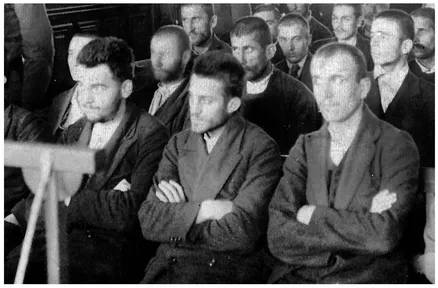

Some were surprised by how slowly the Austrian government responded to the assassination, which seemed to confirm the impression that the assassination would soon be forgotten. Franz Ferdinand was not a popular man in court circles in Vienna; famous for being misanthropic, bigoted and miserly he was one of ‘the least loved of figures in Austrian life’ (Remak, 1959: 11). There were few signs of a popular outcry for revenge among the people of Austria and Hungary. The archduke himself had dreamt of solving the problem of South Slav nationalism by reaching an accord with Serbia when he came to the throne: ‘I do not want from Serbia a single plum-tree, a single sheep’ (Taylor, 1954: 494). However, as is often the case in the course of diplomatic affairs, this tranquil appearance was misleading. A strong conviction quickly emerged within the uppermost levels of the Austrian government that ‘official’ Serbia was responsible for the assassination – even though all of the conspirators had turned out to be subjects of the Habsburg monarchy. Officials in Vienna were convinced that the assassins did not act alone, that they had actually enjoyed the clandestine support of the Serbian government in formulating and executing their plot. It did not take long for the Austrians to discover that the assassin and his compatriots were nationalist zealots, members of an organization called Narodna Odbrana (‘National Unity’) whose aim it was to incorporate all southern Slav peoples within the Serbian state. They failed to discover the connections of the conspirators with a more secretive organization which was prepared to use violence to achieve its ends – the Tsrna Ruka or ‘Union or Death’, more widely known as ‘The Black Hand’ [Doc. 17].

Behind the scenes in Vienna, politicians, diplomats and strategists were hotly debating the question of how far and how fast to move in response. Many Austrian officials regarded the nationalism of minority groups to be the greatest threat to the continuing existence of the multinational Habsburg monarchy and they saw in the assassination the perfect opportunity to crush the Serbian-sponsored independence movement in Bosnia. Although they lacked convincing proof of complicity on the part of the Serbian government, the Austrians, after almost a month of investigation and prolonged discussion, agreed to despatch an ultimatum that they believed Serbia could not possibly accept. The terms went so far that accepting them would, in effect, end Serbia’s existence as a sovereign state [Doc. 34]. The ultimatum was presented at 6 p.m. on 23 July; the Serbs were given 48 hours to comply or face the consequences.

Two days later, when the Serbian government presented its response, it seemed that it had gone as far as it possibly could in complying with the demands while still retaining at least the veneer of sovereignty. In spite of this, the Austrians ordered the mobilization of seven army corps against Serbia. The following day the Russian government, which had warned that it might support Serbia against an Austrian attack, decided to undertake a series of steps that would enable it to institute a full mobilization, should it decide to intervene in an Austro-Serbian conflict. At 11 a.m. on 28 July, less than five days after presenting the ultimatum, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia.

Figure 1.1 Gavrilo Princip and Young Bosnian conspirators stand trial for assassination © STR/AFP/Getty Images

Later on that same day, during the afternoon of 28 July, Tsar Nicholas II authorized the mobilization of his armies – but only in the four military districts closest to Austria-Hungary. This ‘partial mobilization’, which was designed to avoid the appearance of threatening Germany, was initiated the next day at midnight, 29 July. There was precedent for this: Russia had initiated such a partial mobilization in 1912 and it had not led to hostilities; proceeding to a full mobilization would take almost a month. But, by the following day, the Russian foreign minister, Serge Sazonov, had managed to convince a reluctant tsar that restricting Russia’s mobilization to the frontier with Austria-Hungary would place it in a perilous position, should Germany enter the conflict. On 30 July, the tsar relented and ordered a full mobilization. The possibility of confining the crisis to a local, Balkan, affair seemed to have evaporated and a general European war now appeared to be in sight.

Austria-Hungary responded to the Russian decision by ordering a general mobilization the next day. War between the Russians and the Austrians now appeared to be almost inevitable. Consequently, the German government ordered its army to mobilize and despatched an ultimatum of its own to Russia demanding that it cease all military measures against Germany and Austria-Hungary within 12 hours. When the Russians failed to reply to this ultimatum, the Germans declared war on them at 6 p.m. on 1 August. The French ordered a general mobilization on the same day. The next day the German government demanded that Belgium promise to remain neutral and allow the passage of German troops in order to attack France. On 3 August, the Germans declared war on France, and on the morning of 4 August German troops crossed the Belgian frontier. By midnight Germany and Great Britain were at war.

Explaining causes

The preceding summary is obviously superficial. Entire books have been written that cover only the events outlined here in a few paragraphs. Nevertheless, students may still begin to have some sense of the complexities involved in answering the deceptively simple question of ‘how did the war begin?’ No one, not even the Austrians, went to war for the sake of Franz Ferdinand, and yet a direct line can be drawn between his murder, the diplomatic crisis that followed, the mobilizations of the European armies and the official declarations of war. There must have been more to the ‘July crisis’ than meets the eye – more than the public ultimatums and mobilizations. Why did the Austrians attempt to eliminate Serbia as a sovereign state? Why did the Russians decide to risk war by mobilizing in support of the Serbs? Why did the Germans become involved in a dispute that apparently had little to do with them? Why did the French decide to mobilize their troops when war broke out in the east? Why did Germany invade Belgium, and did Britain go to war in order to uphold Belgian neutrality? And where were the Italians? – although members of the Triple Alliance for 34 years, they did not enter the war until May 1915.

In order to answer these questions, we must unravel the diplomatic ties that connected these events to one another; we must understand what the ‘alliance system’ was and how it bound – or failed to bind – the states of Europe to one another. In the aftermath of the First World War, many acute observers insisted that it was the system of alliances that led to the slippery slope to war in July 1914. The impression that once the crisis had been provoked by the assassin’s bullets the alliance system took over and rendered diplomats virtually helpless became widespread after 1919. More recently, it has been argued that the two alliance blocs did as much to mute conflicts as it did to escalate them, but that ‘without the blocs, the war could not have broken out in the way that it did’ (Clark, 2012: 124). The complicated network of political commitments made in these alliances had, in turn, led the general staffs of the European powers to produce intricate mobilization plans, which eventually led to War by Time-Table – the title of one popular book on the subject (Taylor, 1969).

But statesmen seldom act on the basis of simple legal commitments, and even when we unravel the entangling alliances and alignments that tied the states of Europe to one another, we shall only discover another layer of more fundamental – and more profound – questions that require answers if we are to understand how a great European war began in August 1914. The alliances are, in many respects, the easiest subject to explore when studying the origins of the war: they are well-documented; their terms can be analysed; their effectiveness can be measured. But the Italians managed to avoid living up to their promises, while there was nothing on paper that bound the British to the Russians and the French. So what were the ‘underlying’ causes of the war? What sentiments and emotions, ambitions and fears prepared governments and peoples alike to gamble their existence in 1914?

Of all the phenomena associated with the outbreak of the war, nationalism is obviously the one that has most fascinated historians. Part of this fascination can be readily explained by the events of July: nationalism was unquestionably the force that propelled the young Serbs of Bosnia into plotting the assassination of Franz Ferdinand; nationalism was unquestionably the phenomenon that the Austrians saw themselves fighting against when they presented their ultimatum; and the feeling of brotherhood based upon a common Slavic identity was unquestionably a factor in leading the Russians to regard themselves as the protectors of the Serbs. But the interest in this phenomenon far exceeds the events of July; almost every historian engaged in writing the history of Europe has identified nationalism as one of the most influential forces that shaped its modern history. Or, to put it another way, no historian has argued that the sense of nationality was not a factor in the outbreak of war in 1914.

Only slightly less elusive than the idea of nationalism is that of militarism. By the time that the crisis came in July, the continental states of Europe had amassed standing armies of unprecedented size. The conscription of millions of young men by their governments to serve in the armed forces for one, two, or even three years was the rule in pre-war Europe, to which Britain was the exception. This undoubtedly attests to the power of the modern state, both in terms of the power that it can muster, but also in the sense of being able to insist on the compliance of its citizens. Were the young men of Europe forced to the front against their will in 1914? Or does this phenomenon indicate a popular tide of warlike enthusiasm among the peoples of Europe that overwhelmed the statesmen who were unable to stem the tide of the forces that they had unleashed? In Russia, following the disastrous defeat in the war with Japan in 1904–1905, ‘play companies’ (poteshnye roty) were organized throughout the country and by 1912 over 100,000 boys had signed up to demonstrate that they did not lack patriotic fervour and a sense of duty (Sanborn, 2007: 218). Even in Britain, with its tiny professional army, amateur militarism was a popular entertainment before the war.

And what was all that marching and drilling supposed to achieve? What were all those symbols of nationality and patriotic zeal supposed to inspire? Did they not all boil down to imperialistic expansionism? The late nineteenth century was the great age of European dominance: Africa had been partitioned; much of Asia was ruled by Europeans; the Ottoman and Chinese empires appeared to be on the verge of collapse. Was the war within Europe really a struggle for spoils beyond it? Did European governments not consciously manipulate their people into supporting their drive to acquire new resources and markets by promoting xenophobia and inspiring war scares? Is it not true that the war within Europe was really a contest to see who would be master outside of it?

Nationalism, militarism and imperialism are the most prominent of the ‘underlying’ causes of war that historians have investigated in their attempts to go beneath the surface of the events that led to war in 1914. Historians began assessing these factors even before the war ended, and they are assessing them still; students who turn to the ‘classic’ treatments that appeared between the wars in books by Sidney Fay (1928), and Bernadotte Schmitt (1930) will find these themes being clearly discussed from the beginning. The more detailed, better documented, accounts that appeared after the Second World War in books by William L. Langer (1950), A.J.P. Taylor (1954), Luigi Albertini (1952–1957) and Pierre Rénouvin (1962) will find that these themes were not abandoned. It has been apparent from the start that these are the issues that will not go away and that, although it is impossible to assess the relative effect of such factors in some neatly hierarchical manner, it is essential to investigate the factors that altered perceptions, stimulated ambitions and generated fears. Any attempt to explain the origins of the war must take them into account.

One line of investigation not pursued in the English-speaking world until half a century after the outbreak of the war, was the possibility that war arose from the desire on the part of the guardians of the old order to forestall a social conflict at home by engaging in war abroad. This argument was first posed in Germany by Eckhardt Kehr, a radical young historian who, in a number of essays, argued for Der Primat der Innenpolitik (the primacy of domestic politics). Kehr’s argument that the industrialists and landowners of pre-war Germany combined to prevent domestic reform through a policy of Sammlungspolitik (‘the politics of rallying-together’) took hold with a number of influential historians in Germany (Kehr, 1975). This argument was then extended to explain how a crisis – or even a war – would come to be seen by those who were making the decisions to be a more attractive alternative than domestic reform (Mayer, 1967; Gordon, 1974). During the past twenty years, historians have applied elements of this thesis to explain the policies of Britain (Offer, 1985), Russia (Lieven, 1983) and Italy (Bosworth, 1979).

It may now be difficult for us to imagine a time and a place in which war was not only acceptable but popular. For students, the greater the gap in time between themselves and their subject, the more difficult it is to recapture the attitudes and the ideas that made up the emotional world in which Europeans lived early in this century. Two world wars, numerous revolutions, a great depression, the advent of atomic weapons, bloody ethnic conflicts and the rise of widespread terrorism separate us psychologically from the men and women of 1914. The kind of thinking that led people to rejoice at the prospect of war is now difficult to recapture – but rejoice many of them did: there was dancing in the streets and spontaneous demonstrations of support for governments throughout Europe; men flocked to recruiting offices, fearful that the war might end before they had the opportunity to fight; there was a spirit of festival and a sense of community in all European cities as old class divisions and political rivalries were replaced by patriotic fervour. Students seeking to understand the origins of the First World War must be sensitive to the emotional distance that separates them from their forebears.

But students of history should also understand that distance can be an advantage. The question, ‘how did the war begin?’ was frequently posed immediately after the war but in a very different political climate; people were then less concerned with the academic question of how the war began than they were with determining who should take responsibility for it. In Germany this quest was particularly passionate, where it came to be known as the Kriegschuldfrage (the ‘war guilt question’), a question that arose directly from the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. There, the ‘Commission on the Responsibility of the Authors of the War and on the Enforcement of Penalties’ concluded that the responsibility for the outbreak of war ‘lies wholly upon the Powers which declared war in pursuance of a policy of aggression’. Not surprisingly, the victorious powers determined that Germany and Austria (together with their allies, Turkey and Bulgaria) had premeditated the war, and had brought it about by acts ‘deliberately committed in order to make it unavoidable’.

No doubt this assessment of blame would in itself have aroused wounded feelings within Germany and Austria. But in inter-war Europe there was more than wounded feelings at stake because the victorious Allies went on to justify their demand for reparations on the basis of the commission’s report. So the debate on war origins had a practical as well as an abstract side to it, and the question of war guilt quickly became the most hotly debated historical subject of the 1920s. Those who regarded the Treaty of Versailles as an illegitimate, wicked peace, as a diktat imposed by the victors upon the vanquished, believed that if they could show that the burden of responsibility rested more with the Allied states than with the Central Powers (or at least that responsibility must be shared equally), then the peace settlement might be revised and a morally defensible system of international relations put in its place. Conversely, those who believed that the power of Germany had to be permanently checked, and that the Austro-Hungarian monarchy was an evil and decadent empire that must give way to new states based upon the principle of nationality, sought to prove that the commission was correct to conclude that the Central Powers were responsible for the war.

But with the rise of Hitler, the creation of the Third Reich, the outbreak of the Second World War and the horrors of the Holocaust, the controversy over the origins of the First World War gradually lost its hold on the popular imagination. Professional historians continued their investigations of the subject, exploring what seemed to be an endless supply of new documentary evidence, but the subject had lost its punch. In the 1920s, fresh revelations unearthed in the archives or the appearance of new memoirs had been front-page news. Led by Germany, each of the combatants began to compile documentary collections of diplomatic correspondence in the expectation that these would demonstrate their innocence. It soon became obvious that no one was ‘innocent’. The documents revealed an extremely complicated diplomatic system, a network of alliances and alignments and a variety...