1. Introduction: Sociological Imagination and Global Blue Jeans

This may seem like a strange request, but take a moment to look down at your legs. Now look at the legs of the people around you. Chances are that you—or somebody close to you—is wearing a pair of jeans. Around the globe, more than half of the world’s people are wearing denim jeans on any given day (Miller 2010: 34). Marketers estimate that on average, humans wear jeans 3.5 days a week, and 62% of people state that they love or enjoy wearing jeans (Miller and Woodward 2012: 4). The average American woman owns eight pairs of jeans, and young girls own an average of 13 pairs (Snyder 2009: 116). Not only are jeans found on billions of bodies around the globe, but they have taken on a special, iconic place in our hearts. In a stylebook devoted to denim, the authors write: “Loving a pair of jeans is like loving a person. It takes time to find the perfect one and requires care and mending to make it last” (Current et al. 2014: 7).

How did denim come to be such a widely accepted and beloved uniform? Our favorite jeans feel personal and unique, especially as they are washed and faded, molded over time to match our body shape. At the same time, jeans are a mass-market good produced by myriad anonymous laborers and shipped from thousands of miles away. These everyday pants are often taken for granted, but when examined closely, jeans raise some interesting questions. For example, how did a piece of clothing that was historically developed to outfit miners, factory workers, and cowboys evolve into a high-fashion item that can be paired with heels or a suit jacket? Why are jeans a wardrobe classic for many, but also a key piece within changing fashion cycles that float in and out of style (e.g. skinny legs, flares, and overalls)? Why are some people content to buy basic, low-budget jeans, while others shell out hundreds of dollars for a pair of distressed designer jeans with holes in them?

To address these jean-related questions, we need more than a keen fashion sense. We need sociology. Sociology helps us find the meaning in the mundane. Rather than dismissing everyday trends like jean wearing as inconsequential, sociologists explore the meanings and motivations behind our daily decisions. Sociology pushes us, and also trains us to explore connections between our individual lives and broader social factors—that is, to develop a sociological imagination*. This term was coined by C. Wright Mills, a 1950s sociologist who had a reputation for being a bit of a badass. (Mills rode a motorcycle, and he probably taught his classes wearing jeans.) For Mills, developing a sociological imagination allows us to see the connections between “private troubles” and “public issues”. Without a sociological imagination, we tend to reduce our private issues to personal failings and foibles: I shop too much because I just love new stuff. I am unemployed because I am lazy. When you have a sociological imagination, you are able to connect personal issues to larger social structures and historical context. You then start to ask questions like, why do you feel the way you do about your appearance? How are social groups formed and consolidated through clothing choices? How do the relations of capitalism and globalization shape the choices that are available to us as consumers?

Using our sociological imaginations, we can better appreciate the multiple meanings underlying everyday clothing choices, and also identify the social significance of jean wearing. In one jean-focused study, researchers Daniel Miller and Sophie Woodward spent time with people in London, England, asking questions about their everyday lives and clothing habits (Miller and Woodward 2012). These researchers discovered that jeans play a paradoxical role in many people’s lives. Wearing jeans allow people to feel “ordinary”—like an average person who fits in with the crowd. At the same time, jeans are often used to make a person feel special and unique; they might buy a new pair of jeans for a special occasion, or feel proud of their appearance in a particular pair of jeans. In other words, the meaning behind jeans is incredibly versatile, allowing the wearer to feel both part of the group, but also like a unique individual—a finding that goes a long way to explaining jeans’ widespread popularity. This finding was especially poignant for people who had immigrated to the United Kingdom (UK), and wrestled to feel at home in a new land. For example, Miller and Woodward talked to a Sri-Lankan born mother and her teenage daughter about their clothing choices. For the mother, wearing fashionable skinny jeans was a way to feel connected to London fashions as well as her teenage daughter’s youthful spirit; jeans allowed her to craft a new identity distinct from her traditional upbringing where she was expected to wear a sari (Miller and Woodward 2012: 34–5). Of course, not every immigrant to London wears skinny jeans, and the exceptions can be as revealing as the jean-wearing norm. Another woman in Miller and Woodward’s research study, Fatima, eventually stopped wearing jeans after she was harshly criticized by her family (her mother, her brother, and finally her husband) for being “too big”, and told “you look really bad in them”. These two examples reveal that jeans are a way for people to feel included and excluded in social life. Jeans may seem simple and commonplace, but when approached with a sociological imagination, they reveal a great deal about the meanings and power relations underlying everyday life.

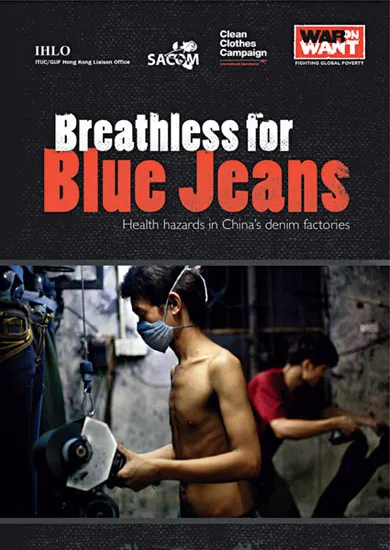

The meaning of jean-wearing is not the only interesting factor here: sociology can also help us think about how we come to own jeans in the first place. Today, very few people have experience sewing their own jeans, let alone weaving their own cloth. To get jeans, most people need to go shopping. To understand how jeans end up on store shelves requires a look at their complex global backstory. The design process may take place in Italy, the cotton may come from Turkey, the jeans may be assembled in China, and the “distressed” look may be created by hand in a Mexican factory. Jeans are the consummate globetrotters. Cotton thread is sourced from around the world and mixed together to make a consistent product over time; a single foot of thread might contain fiber from the United States, Azerbaijan, India, Turkey, and Pakistan (Snyder 2009: 46). As with other globally produced goods, the trend is for the cheapest jeans to be made in the cheapest labor environment, often in conditions where workers put in long hours and earn very low wages. Premium jeans that cost $200 are more likely to be manufactured in the United States or Japan; in contrast, a pair of moderately priced jeans is more likely to be made in China. One region of China, Guangdong, makes half of the world’s jeans, and labor activists have criticized these factories for alarmingly long hours, low wages, and dangerous working conditions (CCC 2013).

Distressed Jeans by Distressed Workers

Once you have purchased your jeans, you may feel good in them for a while, but eventually, you may wonder if your jeans are looking a little dated. Living in our contemporary consumer culture, we often feel pressure to buy something new—to upgrade our worn-in jeans with a fresh new pair. If your old jeans feel dull, you have options for new jeans that are colored (or white for summer), ripped, skinny, flared, boyfriend-style, made with raw denim, or emblazoned with a high-status logo like Diesel, Nudie or 7 For All Mankind. When you live in a capitalist economy, you are surrounded by opportunities to buy something new, and it is often difficult to be content with your old, familiar stuff. This can be irritating at times—especially if you feel like you are spending money just to stay on top of trends—and create stress for those on a limited budget. At the same time, shopping can sometimes feel intensely meaningful, even liberating. One Italian sociologist who interviewed teenagers in Milan found that people formed an emotional relationship to their jeans; teens talked about loving their jeans, not wanting to throw them out even when they were no longer wearable, as their jeans helped them to feel physically attractive (Sassatelli 2011). From an early age, many of us feel that our stuff says something about who we are and what matters to us. While we go to stores to purchase life’s necessities—clothing to cover our body, and food to fuel our actions—most of us don’t shop only for necessities. We often find ourselves shopping for items that give us pleasure and avenues for self-expression, even though it’s hard to pinpoint exactly when or how certain consumer items came to feel pleasurable and satisfying. The norms and desires of consumer culture often get into our heads in subtle, relatively unconscious ways. We may find ourselves buying things we once thought ridiculous, unnecessary, or unfashionable. One student described it to us this way:

Often I am completely unaware of why I like something or why I have grown to like it after having rejected it. For example, I disliked skinny jeans when they first became an important fashion piece, and now I can’t imagine my wardrobe without them.

(Diana, Colombian-Canadian)

How can we mock things like skinny (or high-waisted) jeans one day, and then find ourselves thinking of these items as basic necessities the next? More broadly, how do we make sense of shopping decisions that feel personal, but clearly involve forces larger than ourselves?

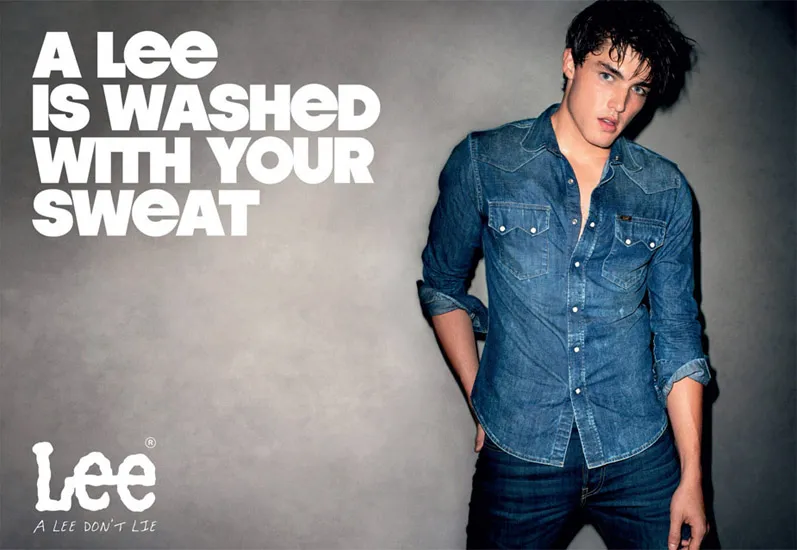

A Lee is Washed with Your Sweat