![]()

Chapter 1

Before the Trip Begins

Fundamental Issues

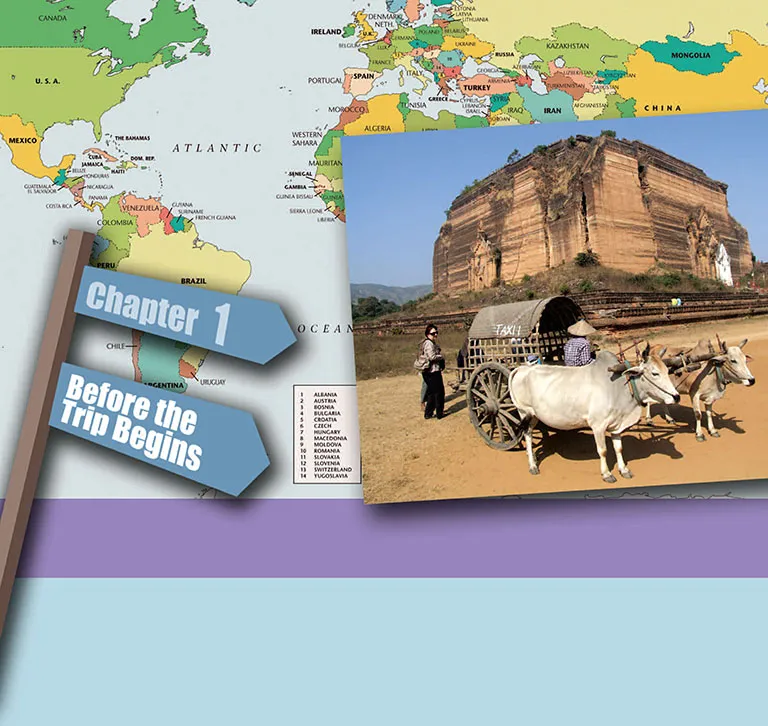

Visitors arriving at Mingun, Myanmar (Burma), on the Irrawaddy River north of Mandalay, are offered "taxi" transport in a covered ox cart to see the base of a gigantic pagoda begun in 1790, eft incomplete, and damaged by a great earthquake in 1839

- What is Music?

- Music: Universal Language or Culturally Specific Activity?

- Beware of Labels

- An Inside Look: Terence Liu

- An Inside Look: Nguyen Thuyet Phong

- Knowing the World's Musics

- The Life of an Ethnomusicologist

- Representation: What Musics Does One Study?

- Resources for the Study of the World's Musics

- Reference Works

- Video

- Audio Recordings

- Journals

- Questions to Consider

What is Music?

Although virtually everyone listens to it and most libraries include books on it, music is notoriously difficult to define, describe, and discuss. While in a literal sense music is only a kind of sound vibration, it must be distinguished from other kinds of sound vibration such as speech or noise. This distinction is based not on observable acoustical differences but on the meanings we assign the sounds that become, in our minds, music. Music is thus a conceptual phenomenon that exists only in the mind; at least that is where the distinctions between “noise” and “music” occur. Graphic representations of music—notations of any sort—are only that, representations. A score is not “the music” because music is a series of sonic vibrations transmitted through the ears to the brain, where we begin the process of making sense of and finding meaning and order in these sounds. Music is also challenging in that it can only be observed in “real time,” that is, over the course of its performance. Most other forms of art—paintings, sculptures, architecture— can be observed comprehensively at a glance.

We are normally surrounded by sounds—the sounds of nature, the sounds of man’s inventions, of our own voices—but for most of us most of the time distinguishing “music” from the totality of ambient sounds around us comes “naturally.” We recognize “noise” when we hear it; we recognize “music” when we hear it. Our sense of the difference between the two derives from a lifetime of conditioning. This conditioning is cultural in origin. Our own concept of what distinguishes music from noise is more or less the same as that of most everyone else within our “culture,” as we were raised in an environment that conveyed to us general notions about the distinctions between the two. Therefore, definitions of “music” are of necessity culturally determined.

For example, some Americans make a distinction between music and singing; for them, the word music refers only to instrumental sounds. Some years ago we wrote to a Primitive Baptist elder (a church leader) in North Carolina regarding that denomination’s orally transmitted hymn singing. We asked—naïvely—“when you sing, do you use music?” The answer was totally logical within the elder’s own world: “We don’t have any music in our church. All we do is sing.” By music we meant notation, but for the elder music meant instruments. In this book, however, we use the term music more broadly to encompass both instrumental and vocal phenomena.

Within the vocal realm, one of the most intriguing distinctions is that between speech and song. At what point on the speech–song continuum does speech become song? The answers to this question vary widely from place to place. Listeners from one culture may easily misjudge sounds from another culture by assuming, based on their own experience, that this or that performance is “song,” when the people performing consider it other than “song.” A general term for such “in-between” phenomena is “heightened speech”; for example, chant. One is most likely to have trouble differentiating “speech” and “song” when experiencing the heightened speech of religious and ritual performances, especially those associated with religions that discourage or even ban the performance of “song.”

In the Buddhist tradition of Thailand, for example, ordained monks are not permitted to perform song. But if you were to attend a “reading” of the great tale of Prince Wetsandawn (the Buddha’s final incarnation before achieving nirvana), during which a robed monk intones a long poem describing the prince’s life, you might, like most Westerners, describe the performance as “singing.” After all, the monk performing the story clearly requires considerable vocal talents to negotiate such elaborate strings of pitches. From a Western perspective this performance sounds convincingly like song. From the monk’s perspective, however—indeed, from that of most Thai— what he is performing cannot be song because monks are prohibited from singing. The monk’s performance is described by the verb thet, which means “to preach.” Why is this performance not considered song? Because there is consensus among Thai that it is not song but rather it is preaching. Thus, this chanted poetry is simultaneously “music” from our perspective and definitely “not music” from the perspective of the performer and his primary audience. Neither perspective is right or wrong in a universal sense; rather, each is “correct” according to respective cultural norms.

Thai Buddhist monks chant the afternoon service at Wat [temple] Suthat, Bangkok, Thailand

Music: Universal Language or Culturally Specific Activity?

It is frequently asserted that “music is a universal [or international] language,” a “meta-language” that expresses universal human emotions and transcends the barriers of language and culture.

The problems with this metaphor are many. First, music is not a language, at least not in the sense of conveying specific meanings through specific symbols, in standard patterns analogous to syntax, and governed by rules of structure analogous to grammar. While attempts have been made to analyze music in linguistic terms, these ultimately failed because music is of a totally different realm. Second, it is questionable whether music really can transcend linguistic barriers and culturally determined behaviors, though some forms of emotional communication, such as crying, are so fundamentally human that virtually all perceive it the same way. In our journey we will come to see that particular musics do not support the notion that music is a universal language, and we do not believe such a concept to be useful in examining the world’s musics.

As will become increasingly clear as you begin your exploration of the world’s vast array of musics, musical expression is both culturally determined and culturally encoded with meaning. The field of semiotics, which deals with signs—systems of symbols and their meanings—offers an explanation of how music works. Although semiotics was not created specifically for music, it has been adapted by Canadian scholar Jean-Jacques Nattiez and others for this purpose.

SEMIOTICS

The study of signs and systems of signs, including in music.

A semiotic view of music asserts that the musical sound itself is a “neutral” symbol that has no inherent meaning. Music is thus thought of as a “text” or “trace” that has to be interpreted. In a process called the poietic, the creator of the music encodes meanings and emotions into the “neutral” composition or performance, which is then interpreted by anyone listening to the music, a process called the esthesic. Each individual listener’s interpretation is entirely the result of cultural conditioning and life experience. When a group of people sharing similar backgrounds encounters a work or performance of music, there is the possibility that all (or most) will interpret what they hear similarly—but it is also possible that there will be as many variant interpretations as there are listeners. In short, meaning is not passed from the creator through the music to the listener. Instead, the listener applies an interpretation that is independent of the creator. However, when both creator and listener share similar backgrounds, there is a greater likelihood that the listener’s interpretation will be consistent with the creator’s intended meaning.

When the creator and listener are from completely different backgrounds, miscommunication is almost inevitable. When, for example, an Indian musician performs what is called a raga, he or she is aware, by virtue of life experience and training, of certain emotional feelings or meanings associated with that raga. An audience of outsiders with little knowledge of Indian music or culture must necessarily interpret the music according to their own experience and by the norms of their society’s music. They are unlikely to hear things as an Indian audience would, being unaware of culturally determined associations between, say, specific ragas and particular times of the day. Such miscommunication inevitably contributes to the problem of ethnocentrism: the assumption that one’s own cultural patterns and understandings are normative and that those that differ are “strange,” “exotic,” or “abnormal.”

ETHNOCENTRISM

The unconscious assumption that one’s own cultural background is “normal,” while that of others is “strange” or “exotic.”

Whenever we encounter something new, we subconsciously compare it to all our previous experiences. We are strongly inclined to associate each new experience with the most similar thing we have encountered previously. People with a narrow range of life experience have less data in their memory bank, and when something is truly new, none of us has any direct way to compare it to a known experience. Misunderstandings easily occur at this point. We attempt to rationalize the unfamiliar in terms of our own experience and often “assume” the unknown is consistent with what we already know. Even if a newly encountered music sounds like something we recognize, we cannot be sure it is similar in any way. Perhaps a war song from another culture might sound like a lullaby in our culture. Knowing about this potential pitfall is the first step in avoiding the trapdoor of ethnocentrism.

Beware of Labels

The German philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) famously warned, “labels terminate thinking.” But because world music is such a vast subject, it must be broken down into manageable subcategories, which are labeled for the purpose of identification. While such labels are useful, they can also mislead. In teaching the musics of the world it is often tempting to use labels as shorthand. Unfortunately, not everyone understands their meanings and limitations; furthermore, these labels are employed in a variety of ways depending on the user’s background. Thus, while we prefer not to employ such labels here, we recognize that they are difficult to avoid. When we do use them, we will attempt to limit them to particular circumstances.

Anyone who aspires to write a music survey, especially one covering the entire planet, cannot avoid using some labels. On the one hand, we recognize the problems with labels, especially the danger of stereotyping and over-generalized statements. On the other hand, a “phenomenological” perspective allowing no possibility for generalizations—emphasizing as it does the individuality of each experience—has no limitations. We recognize the dangers of labels and generalizations but find some of them unavoidable.

Terms that can cause trouble when studying the musics of the world include folk, traditional, classical, art, popular, and neo-traditional. For example, the term folk (from the German volk) carries with it a set of meanings and attitudes derived from the Romantic movement in literature, which flourished in Europe during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. During this period German scholars began exploring their own culture’s roots in opposition to the dominant “classical” culture imported from France and Italy. Romanticism championed the common people over the elite, and in the early nineteenth century, writers such as the Grimm brothers and the pair Arnim von Achim and Clemens Brentano began collecting stories and song texts with subjects often centered on the “peasants,” whose wisdom was seen as equal to that of learned scholars. As a result of its origin, then, ...

![Thai Buddhist monks chant the afternoon service at Wat [temple] Suthat, Bangkok, Thailand](https://book-extracts.perlego.com/2192967/images/fig00006-plgo-compressed.webp)