Brian Wansink—Mindless Eating (2006)

Overeating has moved from an individual problem to a major social problem, with increasing numbers of Americans being classified as overweight or obese, and government healthcare programs being stretched by the added expense. To understand how to get people to eat less, it’s necessary to understand why people eat more—and this is why Brian Wansink, a professor of consumer behavior and nutrition science, founded Cornell’s Food and Brand Lab. There are all sorts of potential explanations for why people overeat—the taste of the food, the smell, hunger—and the job of social science research is to isolate these potential causes and determine which ones really matter.

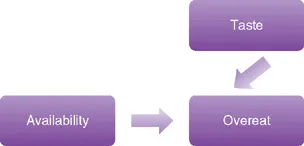

Wansink (2006) argues that the cause of most overeating is the availability of food: People eat more simply because there’s more around. To test this, he designed a series of studies in which he looked at all of the potential causes for why people eat too much. In one of these studies, people in Chicago were given tickets to see the afternoon matinee of a new action movie. When they showed up, the people who were part of the study—a group social scientists refer to as participants, a term which has replaced the older subjects—were given a surprise: a free bucket of popcorn. The movie was scheduled to start at 1:05 in the afternoon, right after lunch, so many of the participants who arrived at the movie theater had just eaten. The goal here was to try and make sure that the participants weren’t eating the popcorn just because they were hungry.

Once they came in, the participants were randomly given either a medium-sized bag of popcorn or an extra-large bucket, which Wansink describes as being “bigger than their heads.” The researchers believed that the participants who were given the extra-large bucket would eat more, just because there’s more available, but there’s a problem. What if the participants eat more just because the popcorn tastes good? In addition to controlling for the hunger of the participants, the researchers also have to control for the taste of the popcorn.

All of these factors—how hungry the participants are, the size of the popcorn they’re given, how good the popcorn tastes—are all variables. The key aspect of variables is that they vary within the study, taking on different values, as opposed to constants, which remain the same. Within society, age is a variable—some people are older or younger than others—so researchers can examine the effect of age. If something is not a variable in the study, it’s a constant, and researchers aren’t able to look at any effects it may have. For instance, if all of the participants in a study are men or college students, then there’s no way for researchers to determine how being a man or being a college student affects whatever the study is looking at.

The variable that a social scientist is interested in explaining is referred to as a dependent variable. The dependent variable is the outcome; the researcher believes that it is caused by the other variables in the model. These variables, the ones that cause the dependent variable, are the independent variables. One of the first steps in any social science study is to think through these variables, and a big part of being a social scientist is seeing the world in terms of independent and dependent variables, cause and effect.

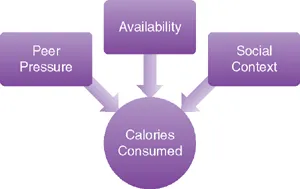

In this case, the dependent variable is how much the participants eat, measured by the amount of popcorn eating and the number of calories consumed. While there is only one dependent variable, there can be multiple independent variables. In this case, the independent variables include the amount of popcorn that’s available and how hungry the participants are.

Problem of Spuriousness

Before Wansink 2010 can be sure that availability leads his participants to overeat, he has to control for other variables, like the taste of the popcorn. What if the reason why people overeat is not simply because the popcorn is there, but rather because they enjoy the taste? Good popcorn might be so warm and buttery that the participants just can’t resist it. Participants who get the larger buckets will eat more because it’s so good. This would be a problem of spuriousness. Spuriousness refers to the unwanted effects of lurking variables (also called confounds, especially in experimental studies), independent variables that aren’t accounted for but have an impact on the dependent variable regardless. If there’s spuriousness, it might look like an independent variable is causing the dependent variable when, in fact, an unmeasured third variable is driving the relationship.

To eliminate this potential problem, Wansink (2006) and his team made sure that no one was eating the popcorn because they liked the taste. Rather than give the participants warm, buttery popcorn, the researchers gave them cold popcorn that had been popped five days beforehand and stored in sterile containers until it squeaked like plastic and was described as being like “eating Styrofoam packing peanuts” by one of the participants. At the end of the movie, the participants were given a survey asking them about how much they had consumed. When asked, “Do you think you consumed more because you had the larger size?” they generally said no. The responses were things like “That wouldn’t happen to me,” “Things like that don’t trick me,” or “I’m pretty good at knowing when I’m full.”

In reality, though, participants who were given the larger buckets of squeaky popcorn ate more. After weighing the buckets, researchers concluded that the participants who were randomly assigned to get the larger buckets consumed 173 more calories, approximately equal to 21 more dips into the bucket. This is 53 percent more than those given the medium-size buckets. Based on these findings, it seems likely that the participants were eating more popcorn not because they were hungry, or because it tasted good, but simply because it was there. Again, the participants don’t say that they’re eating more just because there’s more there—Wansink would argue that they’re not thinking about why they eat at all—but a carefully designed study can allow researchers to know more about why people do things than the people themselves know.

Still, this is just one study, and one of the hallmarks of social science is what’s called triangulation, or measuring the same theory in different ways in order to be more certain about the findings. In addition to availability, Wansink (2006) argues that people rely on social cues in order to decide how much to eat. One of Wansink’s labs also doubles as a fine dining restaurant twice a month, offering an all-inclusive, prix-fixe dinner for less than $25. In all respects, it looks like a high-end fine dining restaurant, with the big difference being that the diners are actually participants in experiments. In 2004, diners on one night got a special treat: a free Cabernet Sauvignon. It was not a special wine, though: it was a $2 bottle of Charles Shaw from Trader Joes (known as Two Buck Chuck). However, the labels of the bottles were changed. Diners on the left side of the restaurant were offered the same wine with a label for Noah’s Winery, located in California. The diners on the right side got an identical label for Noah’s Winery, except the location was listed as North Dakota.

Even though they were given the same wine, diners who were given wine with North Dakota labels had lower expectations and rated the wine as tasting bad and their food as inferior in taste and quality. Diners who were given wine with the California label ate 11 percent more of their food and lingered 10 minutes more at their tables after dinner. Even though the wine and the food provided were identical, the label on the bottle made the diners on the left think of the meal as a special occasion. They ate more without any idea about what was causing them to do so.

Social scientists also have to be careful about the trap of monocausation. While natural scientists often deal with phenomena that have one cause (increased pressure leads to increased heat, for instance), the phenomena that social scientists are most interested in have multiple and overlapping causes. Sorting out all of these causes is made even more difficult by the fact that people are embedded in a social context, and it’s necessary to understand not just how individual-level causes are affecting the individual, but also how the other people around that individual are influencing his or her behavior.

It may seem that Wasink has overeating all figured out, but there are almost always more causes—more independent variables—that could be important. For instance, psychology professor John DeCastro (1990) shows that even the presence of others makes us eat more: Diners eat 35 percent more if they eat with one other person than they would if they dined alone. If people eat with a group of seven or more, they consume 96 percent more food than they would consume alone! Of course, all of these factors may matter more, or less, depending on the availability of food and the social context of the meal, both of which increase the amount that people eat. While there’s one main dependent variable in these studies—the amount that people eat—there are generally many independent variables, enough that the search for more causes is never really over.

In all of the above examples, the unit of analysis was the individual: why one person, rather than another, chooses to overeat. H...