![]()

Humans might be smart, but there is little evidence that we are by nature “economically rational”—that is, that human nature drives people to maximize their independent welfare by accumulating as many material goods as possible. Many of us remember Adam Smith’s dictum that it was a basic part of human nature to “truck and barter”—so basic, according to Smith, that this tendency had probably developed along with the ability to speak. Indeed, modern economics has made this a basic principle for analyzing human behavior. But Smith’s juxtaposition of trade with speech has an implication that his modern disciples have often forgotten—that trade, like speech, could sometimes serve expressive ends. Acquiring a particular good or sending it to others was (and still is) sometimes a way of making a statement about who a person or group was or wanted to be, or about what social relationships people had or desired with others, as much as it was a way of maximizing strictly material comfort. And because economic activities are social acts, they bring together groups of people who often have very different cultural understandings of production, consumption, and trade.

It is certainly true that people have traded things for thousands of years: evidence of the exchange of shells, arrowheads, and other goods over long distances (and thus of geographically specialized production) goes back many millennia before any written records. But in most cases we can only guess at the motives and mechanisms of trade and of the way in which the exchange ratios between different goods were determined. We have evidence that even in ancient times there were some markets in which multiple buyers and sellers competed and prices were set by supply and demand, but also we have a great many cases in which exchange reached a fairly large scale while governed by very different principles. Where supply and demand did set prices, as appears to have been the case, for instance, for many goods in ancient Greece and at roughly the same time in China, and for some goods traded between societies as far back as 2000 bce, the exchange value of goods—what they could fetch in other goods—became more important than their inherent usefulness (use value) or their status. But even price-determining competitive markets were affected by the fact that they were understood to be just one of various ways of exchanging. In the second century bce, the Chinese emperor held a debate at court about whether the state (and the people, though he cared less about them) were best served by competing merchants or government monopolies over crucial goods such as salt and iron; and though the ruler’s decision for monopoly could never be fully implemented even for these goods, the debate reverberated through the centuries, shaping notions of what was and was not acceptable behavior both for unregulated merchants and their would-be regulators.

Everywhere it took a very long time for the concept of prices settled by supply and demand to overcome more traditional notions of reciprocity (equal exchange of goods and favors); status bargaining, which was more ritualistic trading between acknowledged unequals, and usually designed to reproduce that status hierarchy; or Aristotle’s notion of a just price, set not by barter in the market but rather by ethical notions of a moral economy, of just exchanges.

Some people resembled the fleet Ouetaca of Brazil. As we see in reading 1.8 (see page 32), they were what some people today unkindly call “Indian givers”: people who try to take back what they previously got credit for giving. The chase after the exchange was as important as the actual exchange itself. Both parties mistrusted the other, and there was only a very dim sense of property values.

Others were like the Brazilian Tupinamba, who thought the French traders “great madmen” for crossing an ocean and working hard in order to accumulate wealth for future generations. Once the Tupinamba had enough goods, they instead spent their time, according to a Jesuit priest, “drinking wines in their villages, starting wars, and doing much mischief.” And among the Kwakiutl of the Pacific Northwest, giving large amounts of goods away could be either a way of procuring witnesses to one’s accession to a new rank (and of outcompeting for that rank people who could not assemble enough goods to give away fast enough), or a way of deliberately embarrassing a rival; but whether the purpose was to proclaim solidarity or hostility, the giver was the winner, and goods were accumulated in order to get rid of them on the right occasion as ritual gifts or Christmas presents.

Even large-scale, interdependent civilizations were often not based on market principles. The storied Incas of Peru knit together millions of people over thousands of miles in a prosperous, strong state that seems to have had no markets, no money, and no capital. Instead, trade was based upon the familial unit known as the ayllu and overseen by the state. Reciprocity and redistribution were more guiding concepts than profit and accumulation. The Aztecs and Mayas of Mexico also had great empires that engaged in long-distance trade. The Aztecs (see reading 1.7, page 30) enjoyed an enormous marketplace in their capital city of Tenochtitlán (today Mexico City), which hosted as many as 10,000 shoppers and sellers at a time. The Mayas, on the other hand, apparently had no local markets in their considerable cities. Both empires traded goods in an area that stretched from New Mexico to Nicaragua, the equivalent distance in Europe from its northernmost to farthest southern point. Yet long-distance trade was completely separate from the local markets of Aztec cities. Long-distance traders dealt in luxury goods as emissaries of their imperial aristocracies. They were essentially state bureaucrats. These sophisticated long-distance traders would completely disappear once their states collapsed and European merchants arrived.

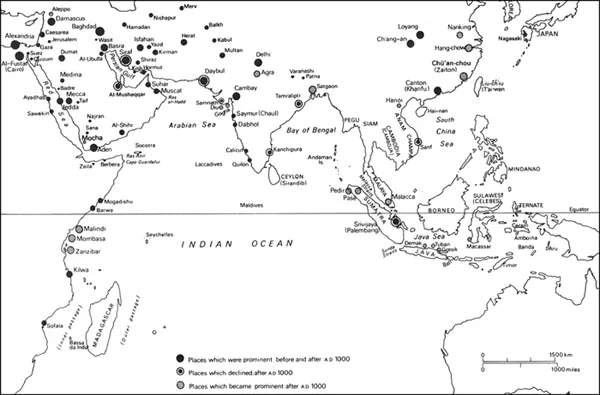

Asia, linked by busy sea networks and so less dependent on difficult overland routes like those used in Peru and Mexico, had much more active private trading. As reading 1.4 (see page 20) demonstrates, diasporas of trading peoples—such as the overseas Chinese, Muslims, and Hindus—joined together an enormous and complex network of commerce (we will return to these trade diasporas shortly). Moreover, the Chinese “tribute system” (see reading 1.2, page 15) helped provide a framework for trade across vast areas of East and Southeast Asia. Though its primary purposes were political and cultural rather than economic, it helped provide an “international” monetary system, promoted shared luxury tastes across a huge area (making the market big enough for specialized producers to target), created quality standards for many goods, and promoted at least some common expectations of what constituted decent behavior. The leaders of ethnic trading communities (see reading 1.1, page 13) provided other elements of a shared framework for trade; so did the accumulated practices in certain long-established entrepôts (usually city-states that were convenient meeting places for East and South Asians because of the patterns of the monsoon winds [see reading 2.1, page 56]). These trading networks were linked to states, but they also had gained a life of their own. Thus, when Europeans finally entered the waters of the Indian Ocean in the sixteenth century and tried to wrest away the trade, they found their Asian competitors resilient. We see in reading 1.4 (page 20) and reading 1.13 (page 20) that for a long while Europeans were treated as simply one more competitor who had to be tolerated, but not obeyed. Unlike New World traders, Asians were less dependent upon their states and hence could persist, even thrive, in the face of European cannons.

But saying that Asian trade was more independent of the state than that of the Incas or Aztecs does not mean that it operated in a purely economic realm outside politics and culture. On the contrary, even “merchants” often derived more profit from state concessions and monopolies than from clever entrepreneurship. Muhammed Sayyid Ardestani (see reading 1.12, page 41) amassed a huge fortune as a tax farmer and a contractor for government purchases. The importance of good relations with government officials was obvious even to the representatives of the English East India Company (see reading 1.13, page 43). In order to impress the Indian princes with whom they dealt, agents of the company spent lavishly to maintain themselves in the lifestyle of local princes and made frequent shows of military power. Being a successful trader required spending as much as accumulating: minimizing costs was not a consistent high priority.

Success for many Europeans in Asia also demanded intermarrying with the local population. Agents of the Dutch East India Company took Malay, Javanese, Filipina, and especially Balinese wives (see reading 1.10, page 37) to implicate themselves in the local market and society. Even though the British and Dutch agents represented some of the first modern capitalist enterprises organized as joint stock companies, they also relied on the traditional means of business alliances: marriage. But while a high-level European marriage generally linked two “houses” in which males controlled the capital and managed thebusiness by exchanging a woman—almost as if she were a trade item herself—in Southeast Asia it was often the bride herself who had the liquid funds and the business acumen (her aristocratic male relatives considered themselves above such haggling). Some European men were delighted to get a domestic partner and a business partner in the same person; many more seem to have found the independent spirit of these women irksome. But for a long time they had little choice but to adapt if they wished to prosper. In fact, the European sojourners often indirectly reinforced the importance of these women even while they (and the missionaries who accompanied them) complained about it. Not being used to the tropics, these men tended to die well before their “local” wives; with inheritances in hand, these women then had even more bargaining chips for their next venture or next marriage.

Europeans often had to “go native” in the first centuries of contact because of their own weakness and because of the variety of local laws and traditions that governed commerce. A diversity of states, religions, and trade diasporas and no agreed-upon commercial law left room for violent disputes. As we see in reading 1.11 (page 39), the intensification of trade in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries led to greater contact and increasing agreements on trade conventions. The spread of Islam also provided an ethical basis for conflict resolutions. But a convergence of practices was not inevitable. In fact, a depression in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries led to a reversal of the trend, at least in what is now Indonesia; commercial customs again became more local and disparate.

Moreover, “native” was a relative term. The typical Asian port housed Gujaratis, Fujianese, Persians, Armenians, Jews, and Arabs, just as European trading centers housed separate groups of Genoese, Florentine, Dutch, English, and Hanseatic merchants. Only the most near-sighted European could fail to see that these groups differed. (The greatly increased power of Europeans in the nineteenth century encouraged such myopia and allowed more Europeans to get away with it, but earlier traders, lacking the aid of a colonial state, could not survive if they were that obtuse.) The individuals who made up these trade diasporas may have expected to leave someday, but the accumulated knowledge, contacts, and ways of operating that each group created were much more enduring—sometimes more important and lasting than the laws of the supposedly rooted local authority.

Under the circumstances, it is not surprising that trade diasporas remained the most efficient way of organizing commerce across much of Afro-Eurasia and the Americas until the nineteenth century, as they had been for centuries (see for instance, readings 1.1, 1.4, 1.6, 1.12, 1.13, and 1.14). Trade diasporas made sense from many points of view. In an era when contracts could be hard to enforce, especially across political boundaries, it helped to deal with people who came from the same place you did. You were likely to understand them better than you did strangers: not only did you speak the same language, but you shared an understanding of what was good merchandise, of when a deal could (and could not) be called off, and of what to do in embarrassing but inevitable situations such as bankruptcy or accident. If you traded with somebody with whom you did not share these understandings, you ran a higher risk of trouble, including having to deal with the culturally alien, sometimes arbitrary, principles of the local ruler’s courts. And in case your trading partners were tempted to cheat you, it helped that their relatives and yours lived near each other. If worse came to absolute worst, there were people to take your anger out on, but more often a shared home base enforced honesty in a less physical way. Somebody who eventually hoped to return home, to inherit his parents’ business or to marry his children to members of other elite families in his home territory, would think twice before hurting the reputation of his family back home. In some cases, this allowed merchant-organized courts back home to issue judgments that their countrymen overseas obeyed; this was true, for instance, for Armenian traders from New Julfa, wherever they lived. In others, no formal institution was created, but people knew that they would pay if they embarrassed their relatives back home.

These principles not only kept traders abroad—two Gujaratis doing a deal in Melaka or Mozambique, for instance—honest with each other; it worked even better to keep either one from enriching himself at the expense of his partners or employers back home. One practice used by Fujianese in early modern times drew particularly heavily on social rank at home to enforce honest dealings abroad. Great merchant families often sent their indentured servants off to manage their most far-flung business interests, especially in Southeast Asia. (Among other things, they may have wished to keep their actual sons at home—for company, for safety, to maximize the chance of grandchildren, or to protect the family’s other interests by managing their land or training to become government officials.) The servants understood that only if they returned home having done well would they be given their freedom, adopted into the family as a son, and furnished with an elite bride selected by their new parents. Until they succeeded, there was not much point in going home.

The rulers of port cities also found it convenient to have trade handled this way. Concentration of wealth in the hands of aliens was less threatening than concentrations of wealth in the hands of, say, local aristocrats who might have the right blood and connections to make a bid for the throne; and if many of the aliens came from the same place, they could be assigned to keep each other orderly. Even Stamford Raffles (see reading 2.6, page 65), who saw himself as a child of the English Enlightenment and professed a belief in the rule of law, not men, found it convenient to organize Singapore (which he founded in 1819) as series of separate ethnic quarters, with a few leading merchants in each quarter responsible for governing according to the customs they were used to. Twenty-five years after that, the founders of the International Settlement in Shanghai initially imagined an all-white settlement where they would rule only themselves; it took a civil war, which brought wealthy Chinese refugees who sent rents soaring, to trump the desire for racial separation and create a mostly Chinese community under Western rule.

In the best of all possible worlds, a ruler might even convince a key figure in a trade diaspora to pay a handsome sum to be named “captain” over his ethnic fellows: if the ruler chose the right person, he got revenue, a grateful (and wealthy) follower, and good government in the merchant quarter at no cost to himself. With so many advantages, trade diasporas remained an indispensable way of organizing trade until full-fledged colonial rule (and with it Western commercial law) was established across much of the globe in the nineteenth century. Even then—and in fact still today—such networks remain an important part of global trade. Condemned by much of Western social theory as nepotistic, irrational, “traditional” (and thus hostile to innovation), various groups of Fujianese, Lebanese, Jews, and Armenians continue to organize trade through ethnicity and to compete successfully with allegedly more rational ways of doing business, even if they work in places as “modern” as New York or Amsterdam. When the past thrives in the present, it is a sure sign that reality is more complex than the blackboard diagrams of either economists or sociologists.

Even when distant areas conformed to European standards of law and values, many other impediments stood in the way. Reading 1.9 (see page 35) reveals the difficult business conditions for an English merchant in Brazil in the years right after its 1822 independence. By this time, European military power was far greater, allowing Europeans to force some reluctant people (and their land and goods) into the kind of market they wanted. Moreover, Europeans had made a quantum leap in methods of producing some goods (such as cloth) at low prices, allowing them to trade on very favorable terms with anyone who wanted those goods. Meanwhile, conventions of trade (and ways of thinking about trade), which fit well with our notions of profit maximization, had come to the fore in Europe, so that Europeans had a much clearer idea of what market conventions they wished to impose in Brazil and elsewhere. Even so, the creation of a world economy was far from finished. Just how far will become clear in Chapter 6, which describes the institutions of modern world trade.

1.1The Fujian Trade Diaspora

Any trader knows that personal contacts matter. But before the age of telecommunications, enforceable commercial codes, and standardized measures, it was even more important to have some nonbusiness tie with your partners, agents, and opposite numbers in other ports. So all over the world, trade was organized through networks of people who shared the same native place—and thus a dialect, a deity (or several) to swear on, and other trust-inducing connections...