![]()

PART

1

Introductory Concepts of Police Management

For new or veteran police managers, understanding the basic ideals and tenets of management styles can serve to improve relations between police agencies and their communities, as well as police managers and their subordinates, and make the managers’ tasks easier. Part 1 of this book provides a historical overview of management and provides examples of issues that lay the groundwork for understanding approaches to management and supervisory positions.

Chapter 1 provides a history of management research and implemented ideas. Much of this background literature comes from industry instead of public service, but the lessons this research provides about the nature of interactions between supervisors and subordinates, as well as the interactions between fellow subordinates, can be applied to law enforcement management. Understanding the balance between productivity and subordinate considerations should help all police managers.

Chapter 2 explores the motivations that police officers have to become police managers, including a discussion of the potential drawbacks that officers should consider. It also explains relationships between philosophy, values, beliefs, principles, and behavior. Understanding these concepts should prove beneficial to police managers in their daily work routines. Because they will affect an entire police department, the policies and procedures as well as the outcomes of the concepts are also discussed.

Because a great deal of a law enforcement agency’s internal interactions, and its interactions with the public, are the result of the department’s culture, Chapter 3 discusses the role of culture. This can be helpful to police managers who wish to change a culture that has developed in a department. It can also be helpful for understanding how departmental policies can impact the culture within a police agency. J.Q. Wilson’s groundbreaking research on policing styles is used as an example of how officer discretion is influenced by a police department’s culture and how the agency head influences that culture.

Part 1 of this book should provide a solid foundation of background material for understanding the more specific aspects of police management that are covered throughout the text. The chapters provide examples and learning exercises that should help the potential or current police manager be better prepared for the challenges of supervising criminal justice personnel.

![]()

1

A History and Philosophy of Police Management

Learning Objectives

- 1. The student will gain knowledge of the background and principles that make up today’s police management.

- 2. The student will become aware of the integration of technical, behavioral, and functional factors with the purpose of achieving stated objectives.

- 3. The student will learn the four levels of organization and why they must work together toward stated objectives in order to justify the trust and respect of the community’s citizens.

- 4. The student will recognize his or her role in achieving the goals of the organization through the most effective and efficient use of assigned resources—people, money, time, and equipment.

- 5. The student will become familiar with the three philosophies of management and how they are employed by police managers today.

Are the problems that confront police managers on a day-to-day basis very different from the problems that confront managers in industry and government? Are they different from those occurring in schools, hospitals, or churches? If we examine materials geared specifically toward industry or government, the answer is a resounding no. The problems facing police managers are similar to those that concern business executives, social leaders, and university personnel. The purpose of the organization may differ greatly from agency to agency, but the management process is quite similar.

What, then, distinguishes the successful and effective police organization from one that is poorly run and under constant pressure due to its ineffectiveness? What is it that causes one police department to be exciting, interesting, and challenging, whereas another is dull, suffers from high turnover rates, and is losing its battle against crime?

The major difference between the effective and the ineffective can usually be traced to the management of the organization and, more specifically, to a difference in the philosophies of management. The differences can be seen in the organizational structure and in the amount of decision-making power granted to captains, lieutenants, and sergeants. The difference is clearly reflected in the attitudes and managerial philosophies of top management personnel.

The Police Manager’s Role

What do police managers do? They listen, talk, read, write, confer, think, and decide—about people, money, materials, methods, and facilities—in order to plan, organize, direct, coordinate, and control their research service, production, public relations, employee relations, and all other activities so that they may more effectively serve the citizens to whom they are responsible. Police managers, therefore, must be skilled in listening, talking, reading, writing, conferring, thinking, and deciding. They must know how to use their personnel, money, materials, and facilities so as to reach whatever stated objectives are important to their organizations.

A study conducted by Harvard Business School identifies three elements common to all successful managers in government and industry: (1) the will to power, (2) the will to manage, and (3) empathy.

This study defines the will to power as the manager’s ability to deal in a competitive environment in an honest and ethical manner and, once this power is obtained, to use it to accomplish the goals of the organization. The will to manage is described as the pleasure the manager receives in seeing these objectives accomplished by the people within the organization. It is important to note that the third quality, empathy, does not stress the manager’s technical ability, but rather the ability to relate to other people and determine how they can best be helped to develop their full potential.

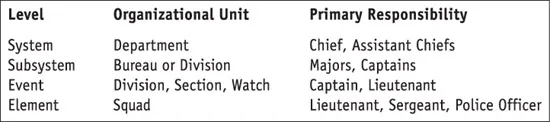

The police manager’s responsibility is to unify his or her organization. There are commonly four levels to an organization: (1) the system—the total organization and its environment; (2) the subsystem—the major divisions or bureaus; (3) the event—a series of individual activities of similar type (normally a patrol watch or detective unit); and (4) the element—the incidents from which service to the community is measured. These four levels of the police department should coordinate in order for the police to reach stated objectives and justify the trust and respect placed in their hands by the citizens of their community.

Many police departments today have more than these four levels of organization. As a result, there is often an overlap of the different levels, and lines of authority and responsibility become unclear. A common problem might exist where a division is commanded by a captain, who is assisted by a lieutenant. The assistant chief in the organization might not be clear on his or her specific role within the division and might make decisions that actually belong to the captain and the lieutenant. As a result of this interference, the lieutenant might begin to make decisions that belong to the sergeant. The sergeant, in turn, might make line operation decisions that should be made by the police officer. The result is that very little decision-making is left to the individual police officer at the element, or bottom, level of the department. (See Figure 1.1.)

Community-oriented policing (COP) helps to maintain a balance among the four major levels within the police department. In agencies in which COP has been successful, usually the only ranks required at the working level are the police officer, the investigator, or the special police officer, all of whom are members of the element level of the department. In a typical COP scenario, at the first-line supervisory level, the sergeant is designated as the individual responsible for coordinating the team’s activities. She is a first-line supervisor, making decisions at the event level, but assisting at the element level. At the subsystem or team level, the lieutenant is designated as the commander. He is responsible for individual team achievements, but leaves the choice of method to the sergeants and officers involved. At the system level is the chief of police and a key assistant, who is called the captain or assistant chief.

Figure 1.1 Organizational Levels.

Police departments have been reorganizing to place a stronger emphasis on the reduction of levels between the top of the department (the chief of police) and the bottom of the department (the police officer). The typical pyramid hierarchy that has been prevalent in the past is slowly beginning to flatten, and this trend seems likely to continue in the immediate future.

Box 1.1 Community Policing

Policing was very different in the 1960s than in modern times. Police had become socially isolated from the communities they were protecting. Technological advances like the automobile and the radio had assisted law enforcement in many ways but had taken their toll by weakening police relations with citizens. As a result of these technological advances, community members rarely interacted with the police in any way other than calls for service. As these problems became more evident, police managers saw the need to return their focus to the community.

Methods of community policing vary widely by jurisdictions. Some agencies reinstituted foot patrol where it was feasible, while other agencies have made simple changes such as having their officers’ name tags include first and last names. Yet despite the enormous differences in implementation, the underlying philosophy of community policing remains the same: to ease interaction between the community and the police. Community-oriented policing (COP) is a form of this. Under this program, police alter their organizations so that reducing fear of crime and order-maintenance through citizen cooperation become central goals. Officers and citizens work together through mutually agreed-upon strategies for accomplishing these goals. However, it is vital that all involved personnel understand that the agency’s central mission cannot be compromised with this plan.

Typically, agencies collect information from a particular community about which criminal justice–related issues are a concern and they jointly develop strategies for addressing them. Officers will be permanently assigned to that beat to help develop relations with the community members and ease communication about community problems and proposed solutions. Obviously, this gives lots of decision-making power to lower-level officers who are working most closely with citizens. COP programs also give the community the opportunity to evaluate the officers, including managers, who are involved in addressing their needs and hopefully create more community satisfaction.

The Management Process

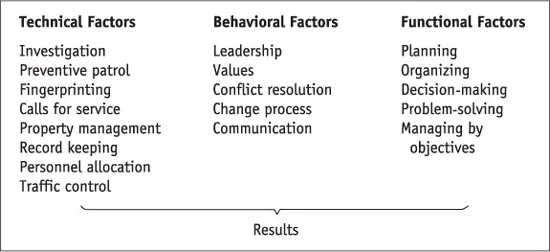

Effectiveness in reaching the objectives of the organization depends on the management process. That process is composed of three major areas: (1) technical factors, (2) behavioral (psychological) factors, and (3) functional factors.

The technical factors comprise skills that are common to all police agencies. They include the ability to investigate crimes and accidents, as well as to perform preventive patrol and execute other routine procedures. These skills are not a subject of this text.

In any organization, the behavioral factors involve the circular flow of verbal and nonverbal communication that is part of everyday operations. These factors deal with human interaction and are essential skills in a law enforcement organization.

The functional factors are those involved in producing desired results. They are designed to assist the police manager in controlling the organization. These factors include planning, organizing, decision-making, problem-solving, and managing by objectives.

The management process is the integration of all these factors, with the purpose of achieving stated objectives. Police managers must utilize both theory and tools so that they may more effectively use the functional factors and behavioral factors in unison with the technical factors, thereby raising the overall level of service provided to the community. (See Figure 1.2.)

Figure 1.2 Integration through management.

History of Management

The history of management can be divided into three broad philosophical approaches and overlapping periods:

- 1. Scientific management (1900–1940).

- 2. Human relations management (1930–1970).

- 3. Systems management (1965–present).

The scientific management theory dominated the period from the beginning of the 20th century to about 1940. Frederick Taylor, the “father of scientific management,” emphasized time and motion studies. His study (1911) of determining how pig iron should be lifted and carried is one of the classics of the scientific management approach. His recommendations for faster and better methods of production, in this case in the shoveling of pig iron, stress the importance of efficiency of operation through a high degree of specialization. The “best method” for each job was determined, and the employees were expected to conform to the recommended procedures. Employees were seen as economic tools. They were expected to behave rationally and held to be motivated by the wish to satisfy basic needs.

Taylor theorized that any organization could best accomplish its assigned tasks through definite work assignments, standardized rules and regulations, clear-cut authority relationships, close supervision, and strict controls. Emphasis was placed entirely on the formal administrative structure, and such terms as authority, chain of command, span of control, and division of labor were generated during this time.

In 1935, Luther Gulick formulated the now famous POSDCORB. This acronym— planning, organizing, staffing, directing, coordinating, reporting, and budgeting—has been emphasized in police management for many years.

Gulick emphasized the technical and engineering side of management, virtually disregarding the human side. Any changes in management during this period were designed to improve efficiency; little or no thought was given to the effect that the change process would have on the officer.

The major criticisms of the scientific management theory as it relates to law enforcement are:

- 1. Officers were considered to be passive instruments; their personal feelings were completely disregarded. Any differences, especially with regard to motivation, were ignored. All employees we...