![]()

Part I

The early Middle Ages, 300–1000

![]()

1 | The end of the Roman Empire in the West |

Every day, one of the most powerful images of Late Antiquity is passed almost unnoticed by thousands of tourists strolling around on Venice’s San Marco Square. It is the Philadelphion (lit. ‘brotherly love’), the reddish porphyry statue of the tetrarchy, the ‘college of the four rulers’, that was cut for the Emperor Diocletian’s palace at Nicomedia (Asia Minor). In 293, Diocletian had decided that the Roman Empire had become too big and too complex to be ruled by one man alone. He made a division in two parts, East and West, each to be ruled by two emperors: one with the superior rank of augustus, the other with the lower rank of caesar. Diocletian understood that such a rule by four could only work if the tetrarchs would be strongly committed to each other and their common cause. Therefore, as first augustus of the East, he gave his daughter in marriage to his caesar, Galerius, while his colleague in the West, Maximian, did the same honour to his caesar, Constantius Chlorus. This close, yet hierarchical, bond between the four tetrarchs is perfectly expressed in the Philadelphion. Each of the two augusti clasps his arm protectively around his junior co-emperor, like a father does to a son. The caesars are indeed represented as young men – which neither of the two in reality was at that time. All four are look-alikes, a purposeful similitudo (‘similarity’) that stresses the unity and harmony, the strength and determination of the imperial junta.

PLATE 1.1 Statue of the tetrarchs, 300–315 CE.

With the installation of the tetrarchy, Diocletian intended to firmly restore peace, unity and prosperity to the Roman Empire after decades of turmoil and civil war. The third century, in particular its middle part, had been beset with all sorts of crises: large-scale barbarian invasions, renewed Persian attacks on the eastern border, mutinies in the army, followed by an avalanche of military coups, massive fall in population, economic decline, impoverishment of the countryside, widespread epidemic disease, rampant inflation following the virtual collapse of the imperial silver coinage.

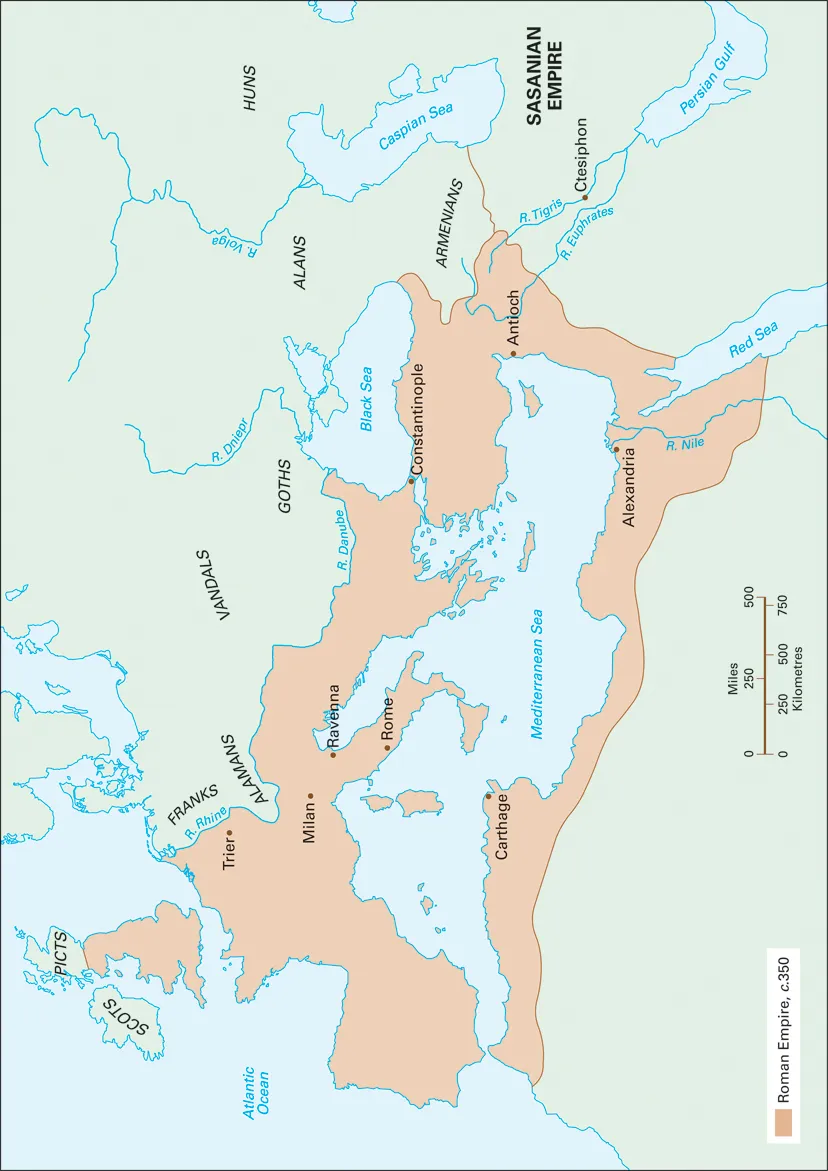

So, the task imposed upon the four rulers was immense. By the beginning of the fourth century the Roman Empire, although borders had already been retreated, still was impressive. It measured about 4.5 million square kilometres, extending over more than thirty present-day states. To get from one end to the other took an average traveller almost three months over land, even if he had made use of the network of paved roads with a total length of around 90,000 kilometres. There were 50–60 million inhabitants belonging to many races and speaking many languages, but all considered to be Roman citizens – provided they were free persons – since 212. Between 10 and 20 per cent of them lived in cities, the largest of which were metropolises of more than 100,000 inhabitants – Rome still being on top with an estimated population of more than half a million. The entire Roman army was about that size too, while between 25,000 and 35,000 state officials were on the state’s payroll – very few people to control and defend a territory and a population of such a size. That is why modern historians are quite divided over the usefulness and the effects of the tetrarchy’s crisis management. There are those who say that during, if not already before, the crisis of the third century the Roman Empire went into steep demographic and economic decline, never to find its way back again. Others argue that, after decline, real recovery followed; that there is no reason to think that the Age of Constantine, in terms of population size and prosperity, was inferior to the Age of Augustus.

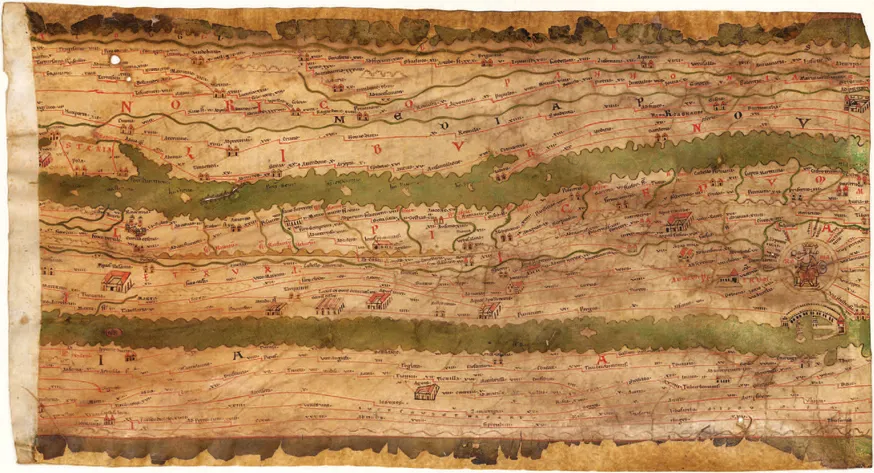

PLATE 1.2 ‘All roads lead to Rome.’ Detail from the Peutinger Table, a copy of a third-century Roman map of roads and watercourses, named after the humanist Conrad Peutinger. Towns and rivers are particularly recognisable.

Governing an empire

Government structure and bureaucracy

To cope with the problems, Diocletian took a number of measures in addition to the introduction of collegiate imperial government. He carried through an administrative reorganisation under which the Empire was divided into two halves, four prefectures (e.g. Gaul, including Britain and Iberia), fourteen dioceses (e.g. Egypt) and 114 provinces (e.g. Africa). Each province was subdivided into civitates or (local) districts, which consisted of an urban centre (sometimes also called civitas, although more usually municipium, urbs or oppidum) and a rural territory (ager) that could extend over hundreds of square kilometres. In addition, there were the two urban prefectures of Rome and Constantinople.

Furthermore, a first attempt was made to codify Roman law; the tax system was streamlined and tax collection more rigidly organised; monetary reforms were undertaken and prices were set at a maximum by law; conformity to state religion was demanded of all citizens. All these measures betray Diocletian’s deeper concerns: to provide for law and order; to secure the state’s tax income; to contain economic vagaries; to enforce religiously sanctioned loyalty to the state. To manage this state intervention on every hierarchical level, the imperial bureaucracy was vastly extended and members of the senatorial order were more often than before appointed to high offices in the upper echelons of imperial administration. The number of senators was more than doubled in the course of the fourth century until it reached about 2,000 at the accession of Emperor Theodosius in 378.

Because all state officials had to be rewarded for their services, the process of bureaucratisation opened the way not only to some measure of administrative sophistication and efficiency, but also to extensive job-hunting, power-broking, leapfrogging and corruption. On paper, everything was neatly, almost militaristically, organised. In real life things were slightly different. Although lip service was paid to professional competence based on formal training, more often family connections, family networking, seniority, money and, in particular, imperial discretion determined who could enter civil service or who was promoted. The only thing the emperor could do against the excrescences of this type of bureaucratisation was to limit the tenure of high officials to prevent them from building up local clienteles.

Emperor and court

The emperor and his court were at the top of government. This summit was quadrupled under the tetrarchy, but soon the tetrarchy and its under-lying aim of non-hereditary collegiate rule proved to be an anomaly. It hardly survived the voluntary retirements of Diocletian and Maximian in 305, mainly because, predictably, most of the augusti and caesars appointed wanted to be succeeded by their sons or favourites, and most were not prepared to share power with others. The project ended in 324, when Constantine, son of Constantius Chlorus, finally had his last rival killed, and became the sole ruler of the Roman Empire. When soon afterwards he considered re-installing tetrachical government, it was meant to be strictly a family business to be run by his four sons. This plan failed even before it was executed because of violent competition among the (half-)brothers, and it all ended in monarchy again, first of Constantine’s third son, Constantius II (337–361), and then of his nephew Julian (361–363), the last emperor of Constantine’s dynasty. When two years later a high-ranking officer, Valentinian, was declared emperor by the army, he was pressed to share imperial power with his brother, Valens. This arrangement set the model for dyarchy rather than tetrarchy, and would lead to the final division of the Roman Empire in an eastern and a western half. Valentinian also stood at the base of the last great imperial dynasty of Antiquity, known as the Valentinian-Theodosian dynasty. It produced emperors without interruption, in the male and female line, until 455.

The emperor’s power could well be described as absolute. Long before they converted to Christianity, Roman emperors enjoyed a semi-divine status, and long afterwards they continued to promote themselves as the embodiment of eternal law and divine providence, if not as the personal vicegerents of Christ on earth. Constantius II used to sign imperial ordinances with ‘My Eternity’. His public appearances were choreographed with precision, and soaked with elaborate, orientalising ceremonies of sanctity. Everything around the emperor was sacred, even the stables where his horses were kept. All such lofty rituals were intended to distance ruler from his subjects. In reality, the emperor’s position was more ambivalent. He was seen both as a demi-god and as the primus inter pares among the Roman citizens. This meant that no emperor could get away with disregarding his ordinary subjects altogether. Carefully staged ‘baths in the crowd’ were made part of imperial ceremonies, and, besides instilling awe and terror, emperors had to display a willingness to grant clemency and favours. This meant that the imperial court attracted a ceaseless flow of petitioners and embassies, usually with the express purpose of redressing decisions taken on a local level.

When not campaigning, the emperor was permanently surrounded by a swarm of women (empresses, princesses, mistresses), friends, eunuchs and other members of the sacrum cubiculum (the emperor’s inner household); their influence was difficult to measure. Others, in particular scions of powerful families, were attached to the emperor’s court on purpose, to spend considerable time under the eyes of the ruler and the handful of high court officials who surrounded him. It happened to Constantine who, as a young man, spent many years at the court of Diocletian in Nicomedia.

The enormous expansion of imperial bureaucracy further down also created problems for the emperors, who found themselves caught between their desire for autocratic rule and the necessity to delegate. Roman emperors could not make use of Orwellian means of mind control; on the contrary, they always ran the risk of getting misinformed or of being kept ignorant. Despite the Empire’s excellent diplomatic and postal service (the cursus publicus), and a sophisticated system of so-called agents in rebus (about 1,200 messengers with special instructions who roamed about in the Empire and acted as the emperor’s eyes and ears), the impact of orders given by the court could easily peter out with the increase of the vast distances they had to travel. Even the symbolical omnipresence of the emperor in statues and on coins, or in the use of his names and titles in documents and inscriptions, could not alter that. The emperor always had to reckon with autonomist tendencies among far-away administrators who could easily fall prey to local interests. The real art of governing the Roman Empire, besides controlling the army, was to forge ‘a working relationship between key members of the departments of central government and key figures in the revenue-producing local communities’ (Heather 2005).

Local government

Local government was concentrated in the urban centres of the civitates, and was led by a city council or curia. Its members, called curiales or decuriones, were invariably recruited from the prosperous local elite. They did not just serve as councillors out of an unselfish commitment to the public cause, but also to exhibit their respectability and gain the opportunity to move up in the expanding state bureaucracy, at which many succeeded. In local affairs, city councils could operate with a large degree of autonomy, also thanks to its own revenues from local taxes and civic estates, ranging from shops to farms and grazing lands in the countryside. But the councils did play a leading part in the governance of the Empire as well. They organised the assessment and collection of direct state taxes (see pp. 21–22), provided for law courts and were responsible for the upkeep of public infrastructure (roads, bridges, aqueducts) and the maintenance of the cursus publicus within their district’s territory. In the countryside, villages had headmen and, increasingly, local clergy and monks for contacts with the authorities, but they rarely seem to have acquired administrative autonomy.

Quite apart from the perquisites of all such administrative duties, many curiales were prepared to pay out of their own pockets for games, shows and free opening hours in the public baths or to sponsor the embellishment of their beloved town with forums, temples, statues, basilicas, arches, porticoes, baths, circuses, theatres or amphitheatres. Monuments of this kind, and the ceremonies, rituals and entertainments that were staged there, went to the heart of both civilised Roman lifestyle and the deeply felt need to openly express loyalty to the Roman order and its first protector, the emperor.

The loss of this monumental splendour, and the ‘disappearance of comfort’ (Ward-Perkins 2005) that inevitably went with it, can only partly be blamed on the barbarian invasions, although these certainly did not help with their preservation. There were two more important factors. One was the advance of Christianity with its anti-secular cultural ideals. Christian leaders strongly opposed pagan luxury and pagan entertainment. Bishop Isidore of Seville, in the early seventh century, warned his flock that they should stay away from ‘the madness of the circus, the immorality of the theatre, the cruelty of the amphitheatre, the atrocity of the arena and the luxury of the games’ – which also suggests that all these attractions were still available in southern Spain at that time. So, this point should not be pushed too far. Moreover, enormous amounts of money, confiscated from funds related to the old public cults, were spent on the building of churches that still looked very much like pagan basilicas. The other factor seems to have been more ponderous, and is related to the steady disappearance of the classical city councils during the fourth century. There were a number of reasons for this. One was a growing interest among urban elites to acquire positions in the imperial bureaucracy or the clerical hierarchy of the Christian Church, rather than in local city government. It seems that the position of curialis had become less attractive mainly because Diocletian’s fiscal reforms had made local tax collection less lucrative and more risky. In the other direction, city politics started to get more and more dominated by another kind of people, the ultra-rich honorati (‘honourable men’), most often wealthy landowners from the senatorial order. In city governments they saw their interests represented by new types of officials who were appointed from above and who had titles such as defensor, protector, curator or, most importantly, comes (civitatis). They would preside over city councils and courts of justice, and as a rule were assisted in the exercise of their duties by the local bishop, who as the leader of the Christian community of a civitas, demanded a say in its politics.

All these developments diminished the political and social importance of the old-style curiales. Although the emperors have tried to stop this process by passing imperial edicts in which curial duties were made obligatory for wealthy citizens, or, at a later stage, decurion status was made hereditary, these did have little effect on the ground. The outcome was not just exchanging one oligarchy for another. Unlike the old curiae, the new governing elites were not constitutionally defined, and their members did not recognise a collective responsibility for their administrative dealings, let alone accept any financial liability. In short, the breakdown of the old-style city councils meant the disappearance of a type of corporate government of well-to-do citizens, bound by a collective commitment to their city and the state, which for centuries had been the cornerstone of Roman power and Roman civilisation. It was also the kiss of death for the ‘competitive munificence’ (Liebeschuetz 2001) that had ensured the monumental grandeur of so many Roman cities.

MAP 1.1 The late Roman Empire, c.350 CE

Taxation and fiscal policy

If the higher purpose of the Roman state was to provide its citizens with peace, legal certainty, justice and prosperity, the most important means that stood at its disposal to reach – and secure – these goals were taxation and the army. It has been calculated that about 5 per cent of the Empire’s GNP went to tax payments (normal for developed pre-industrial states or underdeveloped modern countries), and that well over half of the total tax revenues were spent on the army. So, the Empire’s survival crucially depended on the smooth running of the fiscal machinery.

Diocletian carried through a number of drastic reforms of the two general flat taxes that already existed and which brought in the bulk of the tax revenues, that is to say, the iugatio or land tax (from iuger, the standard area measure) and the capitatio or poll tax/head tax (from caput, ‘head’). First, he joined these two taxes together into one undivided tax, known as iugatio-capitatio or (in Greek) syntheleia. Second, he standardised and refined the assessment basis. Third, he standardised to five years the time interval between the censuses that were conducted to assess individual taxpayers’ tax liability. Fourth, he introduced the so-called indiction (from indictio or ‘notification’), to be understood as the public announcement of the total amount of taxes that each province had to pay yearly. Fifth, he had the reassessment intervals of indiction and census synchronised. This meant that every five years – in 312 prolonged to every fifteen years – new censuses were conducted and a new indiction was established on the basis of census data. Until far into the Middle Ages the late Roman indiction as a fifteen-year period was used in the dating of charters, although its connection with taxation had long gone lost.

Two aims of Dio...