Children’s Place in History and Culture

Before we embark on either description or explanation of the course of ‘child development’, let alone before we consider what efforts we might make to change its course, I must stress that although ‘child’ and ‘development’ may seem to be simple unproblematic concepts, they are not. In particular they are inextricable from beliefs about how to bring up children. There are many variations between cultures on what they believe children ‘naturally’ are and how they ‘should’ behave (Montgomery 2009; Meadows 2010; Mistry and Dutta 2015). There are differences within cultures. There are also historical changes within societies. I will begin by showing some of the complexities and ambiguities of the two concepts that we must not leave unquestioned.

These two are typical late nineteenth century children; though we should remember that they are seen when waiting through a long exposure time for the photograph, and in their best clothes.

The history of childhood has received less attention than it deserves, and it suffers from a patchiness of facts (Pollock 1983, 1987; Houlbrooke 1984; Stearns 2015). Children’s (and women’s) lives are not so well recorded as men’s. Laslett (1971, p. 109–10) writes of the ‘crowds and crowds of little children [who] are strangely absent from the written record’. A lot of what has been said is controversial. For example, Philippe Ariès’ pioneering study (Ariès 1962) argued that strong concern and affection for children, and a belief that childhood was an intrinsically valuable period, were historically recent developments associated with the rise of the affluent household in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Previously, he claimed, there was no concept of ‘childhood’: children were regarded with indifference by their parents or as inferior miniature adults to be strictly reared and severely punished. De Mause (1976) put forward an even blacker model of maltreatment and cruelty to children – infanticide, beatings, sexual abuse and a casual acceptance of high mortality through infection, accident or child-rearing practices such as wet-nursing or using opiates to quiet a crying child – and not much to support any idea that things might have got better in more recent centuries. Ariès and De Mause have both been accused of selecting their data without much concern for their representativeness, and of interpreting dubious ‘facts’ in unjustified ways. As more evidence is examined, the picture of what was happening to children becomes clearer and more complex. Houlbrooke (1984, p. 155–156) summarized the relationships between parents and young children (in the English family between 1450 and 1700) in a picture which resembles what emerges from the mainly nineteenth century diaries reviewed by Pollock (1983) and the autobiographies from a later period collected by Burnett (1982). The basic assumptions were similar. Parental love was believed to be instinctive. Parents delighted in their children but also had a lot of responsibility for their welfare and whether they grew up to be good (in religious terms, and as citizens). This meant curbing children’s natural inclinations and disciplining them appropriately. Nurture mattered a great deal, and parenting was acknowledged to involve complexity and fine judgement. Nature was also relevant, either through notions like ‘original sin’ or, later, through the recognition of individual differences traceable to genes.

The relationship between what is believed about children, what is prescribed as appropriate child-rearing, and what is actually done is not clear in the historical record, or even today (Stearns 2015). However, different basic theories carry different practical implications. For example, if children are seen as firmly predestined from birth because of innate qualities, largely genetically determined, such as different levels of ‘intelligence’, to be intellectuals or technicians or general workers, the most efficient way of educating them may be to provide separate training in the appropriate roles. Such a system was recommended by Plato in The Republic and might be identified in the tripartite secondary school system set up in Britain under the 1944 Education Act. The research problems will centre on how to make the initial diagnosis of the child’s nature (various psychometricians – Burt, for example – were involved in this) and on how to run the education. If, on the other hand, children are seen as changed and shaped by their experience, with little or nothing in the way of predestined characteristics, initial diagnosis is very much less relevant, and child-rearing and education are just a matter of providing the right experience. Advocates of this view judge the ‘rightness’ of experience according to a variety of criteria. To use two futuristic novels as examples, for Skinner in Walden Two and for the inhabitants of Huxley’s Brave New World the main criterion is fitting happily into and serving society, and a major means to this end is pervasive and skillful conditioning. Huxley, who was (unlike Skinner) hostile to Utopias, incorporates in his techniques of child-rearing and social control elements of genetic selection (and genetic engineering) and chemical control of development and behaviour both before and after birth; he also suggests that for the highly creative and innovative intellectual even this all-enveloping system might not work. Skinner did not seem to be troubled by such libertarian qualms, arguing that an effective system which would make all development smooth and happy would be preferable to ineffective conflict-filled systems and their unhappy results.

Similar disagreements exist about the nature of human nature. Assuming that the infant is nearer to what is ‘natural’ than the adult (a dangerous assumption which I shall seek to question later), infant ‘nature’ has been said to be innately good, better than adults’. Rousseau argued for an education of maximum freedom so that the child’s innate goodness should not be spoiled or his creativity, spontaneity and ability to love curtailed. I say ‘his’ deliberately, since Rousseau saw women as inferior and fit only to be trained to serve males; the history of his own children is unclear, but he claimed in his autobiography to have sent them as babies to orphanages. Despite this personal bad example, the progressive educational movement took up Rousseau’s ideas and this model of the child has dominated early childhood education. Non-interventionist ideas may also be seen in Piaget’s accounts of learning, teaching and cognitive development.

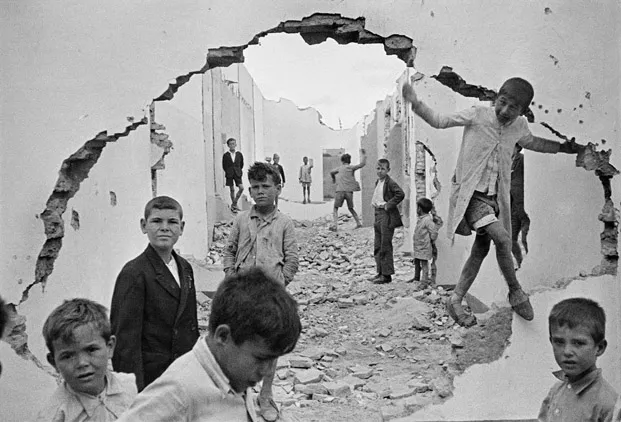

This picture shows the Rousseau ideal of childhood freedom and spontaneity

An alternative view of child nature was the older one of natural badness, Original Sin, unsocialised egocentricity, etc. This view emphasised children’s unpleasant characteristics and prescribed strict, punitive and intrusive child-rearing and education. These took some extraordinarily harsh forms (see De Mause 1976; Stearns 2015), but as I said, there is some debate over whether parents really acted on the advice books (Pollock 1983). Few psychologists would advise harshness now, I think; though some parents feel conditioning babies to a rigid sleeping schedule is excessively harsh. Many psychologists have had in mind, however, views of children as inferior to adults, being, for example, egocentric, dominated by animal instincts, irrational and so forth, and needing to grow out of, or be trained out of, these undesirable faults. And of the giving of doctrinaire advice there is no end (and no consensus in it).

The ‘Biological’, ‘Social’ and ‘Individual’ ‘Causes’ of Development

Underlying all the debate outlined so far is a knot of difficult issues. The core one is the question of the relationship between ‘biological’ and ‘social’ factors in human life, especially human development, since development is often said to be about how the ‘biological’ infant turns into the ‘social’ adult. How to think of this crucial question is a very complex problem, bedeviled by the tradition of separating and opposing ‘biology’ and ‘society’, ‘heredity’ and ‘environment’, and ‘nature’ and ‘nurture’. Once opposed, one pole tends to be valued highly and the other denigrated, and, since neither can alone provide a satisfactory explanation of all human development, there is a history of see-sawings between polar extremes. This is all the more unsatisfactory because ‘biological’ and ‘social’ are not at all clearly separable. Biological facts, such as the physical consequences of possessing a functioning Y chromosome, are acted on by society, which classifies its members as ‘male’ or ‘female’. Social preferences have always been among the forces admitted as working for ‘natural selection’, from Darwin onwards; social changes, such as industrialization, have biological consequences, such as changes in what causes illness or death. Even at the level of the genes, exactly how their instructions work may be strongly influenced by the environment.

Fur colour in Siamese cats

Hofer (1981) gives an example (and I will discuss some examples from humans later):

The amount of dark fur on the feet and nose of Siamese cats depends on the ambient temperature in which they were reared as kittens, the skin on the extremities being normally cooler than other skin areas. The expression of this genetic predisposition depends on the temperature of the skin during a critical period of postnatal development. Raised in an incubator, Siamese cats turn out uniformly light, and if in an icebox, uniformly dark.

(Hofer 1981, p. 10)

The fur colour of Siamese cats is genetially programmed, but also dependent on the temperature of their enviornment during their early post-natal days

Thus even if there is a genetic difference between two individuals, exactly what its influence is will depend on the environment. If every relevant aspect of their environment has been identical, differences between them can be attributed to how their genes expressed themselves in that environment. Reared in a different environment, again exactly the same for both individuals, the genetic difference may express itself differently and the differences between the two individuals’ behaviour be completely changed. Imagine, for example, that one of the two has genes which predispose that individual to highly aggressive behaviour and the other does not. Both are reared in a society which encourages aggression, like the Arapesh tribe described by Margaret Mead, or ancient Sparta. The people with any ‘predisposition for aggression’ will find this a congenial society, will be very aggressive indeed, and will be regarded as satisfactory or even admirable citizens. Those with no ‘predisposition for aggression’ will find it uncongenial, will be less aggressive and less well-regarded, and may have a lesser sense of self-esteem and social acceptability. Alternatively, suppose that both are reared in a society which discourages aggression, as Mead said the Mundugumor did. Success and public approval will come to the genetically less aggressive person; dissatisfaction, low social acceptability and neurosis will come to the other, who is being required by society to suppress genetically ‘natural’ behaviour. Heredity and environment will interact to produce differences not only in aggression, the only part of behaviour where there is a genetic difference, but in other areas of behaviour and thinking which are related to social experience, such as self-esteem, social role and acceptance of social values. Differences in individuals will evoke different experiences, both other people’s behaviour and what environments they get into or are excluded from, via their own ‘choices’ and via how others see them.

Often, boys show a great deal of interest in toy guns: as their culture expects.

This account does not go deeply enough into how genes actually work. There is a complex cascade of ‘cause’ and ‘effect’ between a ‘gene’ and the characteristic it is ‘for’, as I will discuss later, and we need to examine this in every case. We can get ourselves into trouble if we make a too gross simplification of the sort of interaction between genetic programming and experience that really happens in development. In particular, we would be rash to assume that any given environment is ‘identical’ or works ‘identically’ for two individuals, or indeed for two groups. If the environment does differ, it may be these differences as much as any genetic ones which cause differences in behaviour. To take aggression as an example a second time, it is indeed possible that there is a genetically caused difference in aggression between males and females. In many species, our own among them, males are more aggressive in more...