![]()

Chapter 1

Early Colonization and Conflict, 1607–1689

In the seventeenth century, colonization brought people from widely disparate cultures and societies into close proximity in North America. In a few cases, colonial and native groups coexisted peacefully and adapted to one another, establishing mutually beneficial relationships. American Indian peoples often tried to cultivate relations with settlers to gain potential allies against native rivals and access to trade goods. In other cases, competition over land and trade fueled violence. Moreover, Europeans regarded their Western culture and Christian faith as vastly superior to Indian lifestyles and beliefs, which prevented settlers from appreciating native perspectives and concerns.

Prior to colonization, Native Americans and Europeans had each developed distinctive approaches to warfare. But over the course of the seventeenth century, as settlers and Indians interacted, both fought against and with each other, and their military styles were altered. Colonists developed tactics and operations to fight a foe that did not engage in European-style pitched battles, often doing so by employing native allies. Indian tactical and operational practices did not change as much but became married to Western technology, particularly muskets. Assisted by such weapons, warriors at times inflicted levels of killing and destruction beyond what had been typical for native warfare, spurred in part by settlers’ examples.

Colonists came to North America from a number of European countries, including France, Spain, and the Netherlands. Because the experiences of English settlers had the greatest bearing upon later U.S. military institutions, this chapter will focus primarily on the Chesapeake and New England colonies, with some attention to non-English settlements in the northeastern part of the continent. (Students wanting to learn about military experiences in what became Spanish America can visit the companion website to this volume at www.routledge.com/cw/muehlbauer). Whatever their national origin, though, up until the late seventeenth century colonists fought wars of their own volition, with negligible direction or assistance from their mother countries. The next chapter will address North American wars from the late 1600s until the mid-eighteenth century, in which European states took a greater interest.

In this chapter, students will learn about:

- Native American and European approaches to warfare prior to colonization.

- How military practices changed as a result of cross-cultural contact.

- Military experiences and conflict involving French Canada and early Dutch settlements.

- Military experiences and conflict in the seventeenth-century Chesapeake.

- Military experiences and conflict in seventeenth-century New England up through King Philip’s War (1675–76).

Native American Societies and Warfare

A wide disparity of native peoples and cultures inhabited North America in the millennium before European colonization. In the forested eastern half of the continent, most lived in semi-sedentary societies, occupying a few locations over the course of a year to pursue different sustenance activities such as farming, hunting, and fishing, depending upon terrain and ecological conditions. Different autonomous bands and nations often spoke similar dialects within a common language group and shared common cultural practices and folklore. In eastern North America, the two predominant language groups were Algonquian and Iroquoian.

These Indian societies also lacked the social stratification of European ones. Gender and age contributed much more to defining one’s role within an indigenous community. Men, for example, engaged in hunting and fishing for sustenance but also participated in warfare. Women generally maintained households, fields, and gardens. Older people generally held greater responsibility: women, over the disposition of household and community resources; men, over interactions with other native groups, including diplomacy and military decisions. These relatively egalitarian societies also lacked means of coercion. European rulers, for example, had officials and troops to enforce law and suppress revolts against authority. In Native America, however, leaders could persuade, but not force, their peoples to accept their decisions. When an Indian community was seriously divided over an issue, many of its members might leave and either join another native group or establish their own autonomous band.

Various reasons caused warfare between native groups. Often, the issue was access to territory desired for hunting, fishing, or planting. If a people believed that its members had been victimized by another, and diplomacy failed to produce redress, warriors might launch revenge attacks. In the northeast, Daniel Richter has demonstrated that the Five Nations of the Iroquois practiced “mourning war”: When many people died in a community, they dispatched war parties to capture prisoners who they would then adopt. (The Five Nations comprised only some of the bands within the Iroquoian language group.) Seasonal constraints affected warfare, for at certain times of year warriors needed to hunt, fish, or perform other sustenance activities.

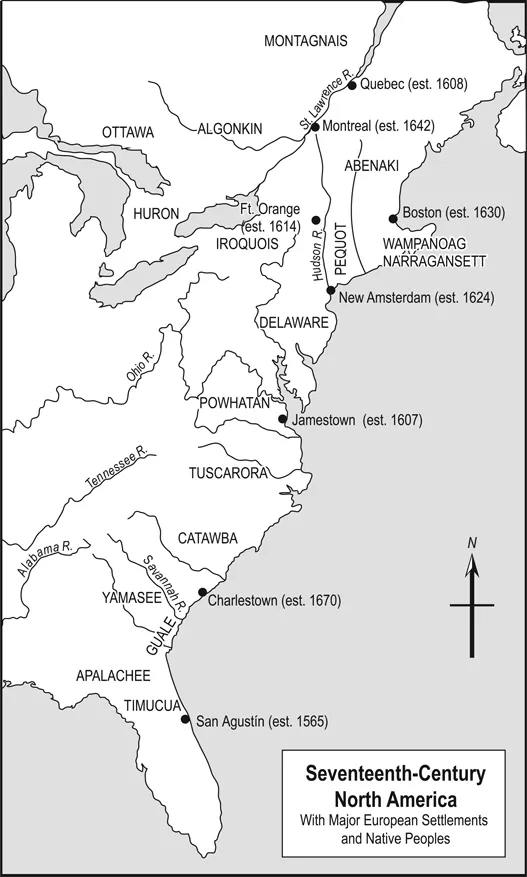

Map 1.1 Seventeenth-Century North America

In the centuries prior to European contact, the intensity of native warfare oscillated. Archeological evidence indicates that, in some places, massacres of large numbers of men, women, and children occurred. The frequency of such incidents, relative to raids and ambushes that produced fewer casualties, cannot be determined with great accuracy. By the period of colonization, however, native peoples generally engaged in combat that was not very lethal, at least by Western standards.

All young men were expected to learn hunting and military skills. Males who had previously proven their courage or ability provided leadership. Although war parties often initiated combat according to a common plan, each warrior acted on his own volition, without waiting for direction from another (such as an officer in European armies). For native men, the capture of loot, plunder, and captives brought success and respect. Warriors killed, and in the seventeenth century adopted the practice of scalping their opponents so they could return home with evidence of their lethality (a practice later mimicked by colonists). But they preferred to take live captives who could then be adopted into one’s home community or released for a ransom (though at times adult male prisoners might be ritually executed).

Tactically, native bands engaged in what is today called “low-intensity warfare,” particularly raids, ambushes, and skirmishes. They generally attacked only when they held the advantage and used stealth and knowledge of local terrain to surprise enemies. Conversely, Indians retreated if attacked themselves, and many native villages had palisades in the seventeenth century to protect inhabitants from marauders. A battle between two prepared and ready forces occurred rarely and usually ended after one side suffered a few casualties. In the Native American context, operations consisted of dispatching war parties to enemy areas where they would raid settlements and camps and launch ambushes. Strategy entailed harming and harassing an enemy people enough that its leaders would concede or compromise on whatever issues had sparked hostilities.

Western Europe and the Military Revolution

In contrast to North American Indians in this era, European society was very hierarchical. During the Middle Ages, rural peasants had labored on lands controlled by a small aristocracy, with limited numbers of merchants, artisans, and craftsmen dwelling in town and villages. In the early modern period, more people moved to urban locations, and the “middle classes” began to grow. The abolition of serfdom in Western Europe allowed peasants to migrate, and commerce expanded, including overseas trade with Africa and Asia. These changes made a significant impact by the seventeenth century, creating some social mobility. But opportunities to acquire enhanced status were limited, and European society remained stratified.

Both the broader changes affecting Europe and its hierarchical nature shaped evolving military forces. From the late fifteenth to the eighteenth centuries, European states grew in size, became fewer in number, and created large, permanent armies and navies. In the Middle Ages standing forces were small, if they existed at all. Monarchs and princes required military service of their nobles in times of war. The latter traditionally served as armored horsemen, and to pay for their expensive arms and equipment aristocrats received control of lands. Nobles often had castles to protect and dominate the nearby countryside. In addition, locals often served in militias to defend their communities. By the sixteenth century, this system was breaking down. Some nobles exploited commercial opportunities to make money and offered rulers funds in lieu of military service. Moreover, technological and organizational changes had already undermined the military dominance of heavy cavalry and traditional fortifications (addressed in the next section).

These and other developments prompted rulers to create large, standing, infantry-based armies. But doing so required other changes: greater taxation and other means to generate public income; larger bureaucracies and administrative capabilities to collect revenues and oversee expenditures; and systems to recruit, train, and lead soldiers. The men who became officers in these expanded military establishments generally had noble backgrounds, and hence the armies replicated the hierarchical structure of traditional Western society. As a result of these developments, the impact of war (and preparations for it) upon European society increased dramatically, particularly in how states—in order to maintain larger armed forces—themselves became more powerful. Some historians call this trend the “military revolution.”

The relevance of the military revolution for early American history is mixed. Colonists did not have the resources or organization needed to maintain large permanent military establishments, and their mother countries only sent small numbers of regular troops to North America before the mid-eighteenth century. The military revolution, however, established what is now called “high-intensity conflict” as the normative form of Western war. Low-intensity hostilities (also called “petit guerre”) composed of raids, ambushes, and skirmishes still occurred in Europe, and in some regions were the dominant form of conflict. But high-intensity battles and sieges were not just distinct, dramatic episodes involving large numbers of trained, full-time soldiers. Their outcomes could have great effects, even determine the outcome of an entire war. As Western states acquired the resources to field large armies capable of fighting big battles and pursuing large operations, Europeans came to see high-intensity conflict as “normal.” Though colonists could not maintain standing forces, this bias often shaped how they approached warfare.

Technological Developments in Early Modern Europe

The Chinese had used gunpowder for centuries, primarily in fireworks, by the time it became known in the West by the early 1300s. Europeans quickly realized the military possibilities for gunpowder, particularly for attacking people sheltering behind castle or town walls, and later for destroying fortifications themselves. But it took a long time to develop cannons that were both strong enough to withstand internal gunpowder explosions and small enough that they could be transported. By the end of the 1400s, such capabilities were realized with the advent of cast bronze guns. A few decades later, cast iron cannons offered another alternative. These were actually heavier than similarly sized cast bronze guns and more prone to corrosion. But iron guns were much cheaper and allowed the English, in particular, to mount large numbers on their oceangoing ships.

By the late fifteenth century, cannons were small enough that they could be placed on carriages and moved by teams of horses. Monarchs could assemble and move groups of artillery, called “batteries,” which would quickly destroy medieval-style castles. However, engineers responded to these artillery threats by designing a new type of fortress called a trace italienne (originating in Italy). These had low, thick walls that could better withstand bombardment. To guard against infantry assaults that threatened to scale walls, these fortresses also had projections called “bastions” that enabled defenders to fire into the flanks of approaching soldiers (also called “enfilade fire”).

Gunpowder also changed infantry weapons. Muskets became the preferred military long arm in the sixteenth century. (Pistols are smaller, shorter-range weapons.) Their barrels were smooth on the inside, making them easier and faster to load but limiting their accuracy and range. Rifles, in contrast, were more accurate with greater range because they had grooves that imparted a spin to a bullet. But these weapons took a long time to load, as projectiles had to be hammered down the barrel, and armies made limited use of them. Both weapons were loaded from the muzzle, or the open end of the weapon where the bullet exited. As with most artillery, these weapons had touchholes drilled into the bottom or back end of the barrels. After powder and bullet were secured down the muzzle, some powder was placed down the touchhole and in a pan on the outside of the barrel next to the hole. A firing mechanism then ignited the powder in the pan, which then spread though the touchhole into the firing chamber, causing the explosion that would propel the bullet out the muzzle.

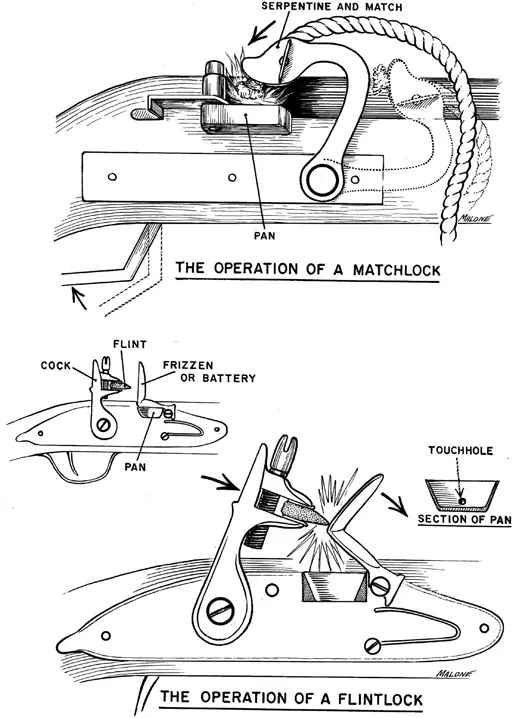

Figure 1.1 Matchlock and Flintlock Firing Mechanisms

Firing mechanisms varied over time and had numerous variants, but two predominated in this era. Matchlock weapons became common in the sixteenth century. Before firing, a user poured gunpowder down the barrel from a container, inserted the bullet and wad-ding, and then placed powder in the firing pan. When a soldier engaged the trigger, the hammer depressed a lit, slow-burning piece of rope (the “match”) into the pan, igniting the powder. Handling such weapons was cumbersome and difficult: Soldiers had to remain some distance from one another to ensure they did not inadvertently light one another’s powder. Over the seventeenth century, flintlock firing mechanisms replaced matchlocks. Engaging the trigger caused a flint to move forward and strike a “frizzen,” which would send sparks into the pan and ignite the powder. Moreover, paper cartridges containing powder and later bullets became common in this period. Soldiers would rip them open with their teeth, pour in powder and then push the bullet and wading down the barrel with a ramrod. Flintlock weapons were less dangerous for the user and more likely to work in wet weather.

Another development accompanied these evolutions in gunpowder weaponry. Due to the numerous steps required, reloading a matchlock weapon took a minute or two, making these soldiers vulnerable to fast-moving cavalry. As a result, musketeers were accompanied in battle by pikemen—soldiers wielding long, strong spears called “pikes.” But the late 1600s saw the advent of the socket bayonet, a blade that could be fitted over a musket that still allowed a soldier to fire it. As a result, armies dispensed with pikemen, and by the eighteenth century, European states equipped almost all infantry with both flintlock muskets and bayonets.

Tactics, Operations, and Logistics in the Military Revolution

These technological developments had a profound impact upon Western warfare, though in one sense they amplified a development that preceded the use of firearms. Tactically, heavy cavalry (armored knights on horseback) had been the dominant type of combat unit on European battlefields for most of the Middle Ages. But the late medieval period saw various battles in which infantry armies prevailed over such forces. The most famous of these was Agincourt, where in 1415 archers and dismounted knights under Henry V defeated a much larger French host. This trend became more pronounced after the spread of firearms: They were relatively cheap and, unlike other weapons, soldiers could become proficient with them in a short time.

In the 1500s, infantry forces usually consisted of “shot and pike.” The former were musketeers, the latter pikemen, and both would form in block-like configurations on the battlefield. Given the dangers of handling matchlocks and gunpowder, musketeers had some space between them, while pikemen usually formed closer together. If cavalry threatened, musketeers would retreat behind the pikes—but pikemen could also charge an enemy. In the late 1600s, the advent of the bayonet made pikemen superfluous. Moreover, the safer firing mechanism of flintlocks along with paper cartridges allowed officers to tactically mass soldiers tightly together in a few long lines that could produce a heavy volume of simultaneous fire or, if close enough, charge an enemy with bayonets. These linear formatio...