![]()

Part

1

Some Primal and Bygone Religions

![]()

Chapter 1

Religion in Prehistoric and Primal Cultures

Facts in Brief

- WORLDWIDE POPULATION IN PRIMAL CULTURES: ca. 94 million

- SACRED TRADITION: Oral, pictorial, or transmitted through artifacts

- CASE STUDIES: Primal cultures of the recent past: The Dieri of Australia Date of study, ca. 1865 Population, ca. 10,000 The BaVenda of South Africa Date of study, ca. 1920 Population, ca. 150,000

- The Cherokees of Southeastern United States

- Date of study, ca. 1825

- Population, ca. 18,000

None of us can hope to see the world through the eyes of our prehistoric ancestors. We pore over their cave paintings, their implements, the disposition of bodies and artifacts in their burial sites, and we make conjectures. We do, however, have a clearer view of primal religions in our own time. (The term primal is here used to refer to religions in an original state, that is, confined to a relatively small cultural setting, isolated, not branching from other religions, and "not exported.") Although there is no clear warrant for interpreting the probable intentions of prehistoric people by analogy to those of more recent primal cultures, we find ourselves taking note of parallels simply because there are no alternative models to inform our suppositions. We should view the analogies with caution.

Conjectures about prehistoric cultures and observations of isolated primal cultures in the recent past converge on one vital function of religion: the linking of the visible, everyday world with powerful unseen forces and spirits. In this regard, the lives of ancient peoples were far more intimately interwoven with the forces of nature than moderns can readily conceptualize. It is our habit to objectify: the sudden storm is a product of colliding air masses; an eclipse is a product of planetary orbits; the deceased grandfather in a dream is a product of brain function. In ancient or primal cultures, the storm, the eclipse, and the dream appear not as objects but as “others” in a subject-to-subject mode. In a profound sense, this meant an enlargement of the scope of religious encounter. To understand such a worldview puts special demands upon our powers of empathy.

I. Beginnings: Religion in Prehistoric Cultures

- O ancient cousin,

- O Neanderthaler!

- What shapes beguiled, what shadows fled across

- Your early mind? Here are your bones,

- And hollow crumbled skull,

- And here your shapen flints—the last inert

- Mute witnesses to so long vanished strength.

- What loves had you,

- What words to speak,

- What worships,

- Cousin?

—J.B. Noss

If we could find answers to these questions, they might help us determine when and how religion began. If the attribution “religious” requires evidence of regularized practices apparently aimed at making sense of the world and controlling nonhuman forces, then the Neanderthals may have been the first to be identifiably religious. Perhaps they were not, but their immediate predecessors (Homo habilis, erectus, and heidelbergensis) —though they left us shaped stone tools, weapons, fire pits, and collections of human skulls—did not leave us a comparable amount of evidence.

The Old Stone Age

Neanderthals

The Neanderthal people, who flourished from 230,000 down to 30,000 years ago over an area stretching from southern Spain across Europe to Hungary and Israel, are regarded today as probably a separate species, replaced by Homo sapiens rather than blending into it. Nevertheless, their graves furnish the earliest clear evidence of religious practice in the Old Stone Age.

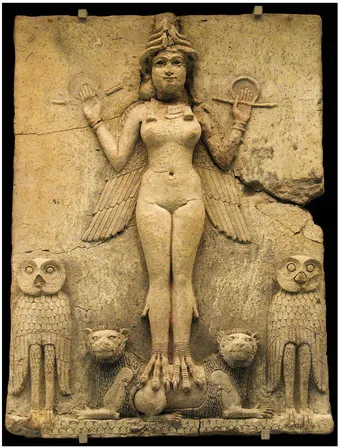

Prehistoric and Primal Sites.

Some of the dead were given careful burial. Alongside the bodies, which were usually in a crouching position, there were food offerings (of which broken bones remain) and flint implements—hand axes, awls, and chipped scrapers. It is generally assumed that such objects were left to serve the dead in an afterlife. Other grave offerings were less utilitarian and more purely expressive: a body in the Shanidar cave in Iraq was covered with at least eight species of flowers! There also are signs of other forms of ritualized veneration.

The Neanderthals apparently treated the cave bear with special reverence. They hunted it at great peril to themselves and seem to have respected its spirit even after it was dead. They appear to have set aside certain cave bear skulls, without removing the brains—a great delicacy—and also certain long (or marrow) bones, and to have placed them with special care in their caves on elevated slabs of stone, on shelves, or in niches, probably in order to make them the center of some kind of ritual. Whether their bear cult, if it was such, was a propitiation of the bear spirit during a ritual feast, a form of hunting magic to ensure the success of the next hunt, or a sacrifice or votive offering to some divinity having to do with the interrelations of human and bear is a matter of conjecture.

Another subject of debate is the Neanderthal treatment of human skulls. Some of the skulls are found, singly or in series, without the accompaniment of the other bones of the body, each decapitated and opened at the base in such a way as to suggest that the brains were extracted and eaten. The evidence is inconclusive about whether the emptied skulls were placed in a ritual position for memorial rites or whether the Neanderthal people were headhunters who ate the brains in some sacramental way of sacrificial victims, the newly dead, or enemies to acquire the soul force in them. The fact that not all bodies were buried intact and that large bones of the human body were often split open to the marrow suggests that human cadavers were a source of food, whether or not they were sometimes consumed in a ritual fashion.

When we come to the later and higher culture levels of the Old Stone Age, beginning 30,000 years ago—to the period of the so-called Cro-Magnon people of Europe and their African and Asian peers—we are left in less doubt about the precise nature of Old Stone Age religious conviction and practice.

The Cro-Magnons

The Cro-Magnons were members of the species Homo sapiens, more fully developed in the direction of the species today and even somewhat taller and more rugged than the modern norm. They came into a milder climate than that which had made so hazardous the existence of the Neanderthal people whom they replaced. In the warmer months, like the Neanderthals before them, they lived a more or less nomadic life following their game; during the colder seasons, they used caves and shelters or lean-tos under cliffs. They lived by gathering roots and wild fruits and by hunting, their larger prey being bison, aurochs, an occasional mammoth, and especially the reindeer and the wild horse. Evidence of their hunting prowess has been found at their open-air camp, discovered at Solutré in south central France, where archaeologists have unearthed the bones of 100,000 horses, along with reindeer, mammoths, and bison—the remains of centuries of feasting. The Cro-Magnons never tamed and domesticated the horse, but they found it good eating. The horse, bearded and small, moved in large herds, was highly vulnerable to attack, and was not dangerous.

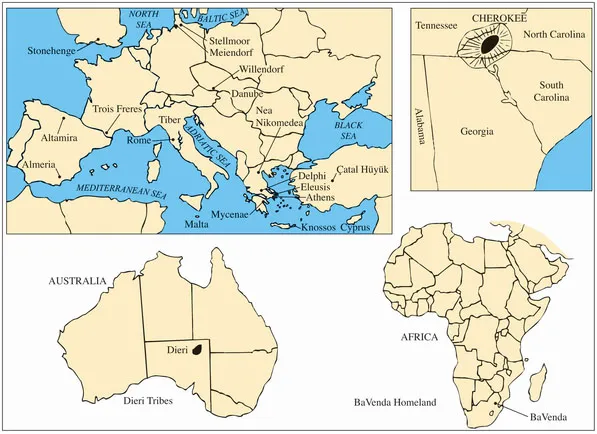

The Shaman of Les Trois Frères This Cro-Magnon shaman wears a costume made out of reindeer antlers, the ears of a stag, eyes of an owl, beard of a man, paws of a bear, tail of a horse, and a patchwork of animal skins. The feet are human. He is perhaps engaged in a hunting dance. (The Print Collector/Alamy)

In a somewhat similar fashion as the Neanderthals, the Cro-Magnons buried their dead, choosing the same types of burial sites, not unnaturally, at the mouths of their grottos or near their shelters; they surrounded the body, which was usually placed under a protective stone slab, with ornaments such as shell bracelets and hair circlets, and with stone tools, weapons, and food. Because some of the bones found at the grave sites were charred, it is possible—but it is conjecture—that the survivors returned to the grave to feast with the dead during a supportive communal meal. Of great interest is the fact that they practiced the custom of painting or pouring red coloring matter (red ochre) on the body at burial, or at a later time on the bones during a second burial.

Cave Painting: Magic for the Hunt

Constantly surrounded as we are by casually produced pictures of every sort, it is difficult for us to comprehend the power that created images must have had for our prehistoric ancestors. Those paintings and engravings that survive were not casually produced. They required an investment of effort that could only have come from a strong sense of purpose.

Caves in the Franco Cantabrian region preserve marvels of Cro-Magnon art (40,000–10,000 bce ). Paintings, clay figurines, and engravings on bone depict human figures, fertility symbols, and especially animals of the hunt: bison, reindeer, bears, and mammoths.

Many of the engravings and paintings were executed on the walls of gloomy caves by the light from torches or shallow soapstone lamps fed with fat. So far from the cave’s mouth and in such nearly inaccessible places did the artists usually do their work that they could hardly have intended an everyday display of their murals. What then did they have in mind?

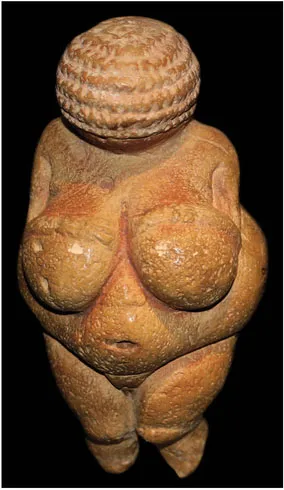

The “Venus” of Willendorf The conventional “Venus” ascription is inappropriate. This Upper Paleolithic limestone figure is not a goddess of love in a pantheon of deities, and she is not a model of seductive beauty. The ovoid abdomen and thighs and the thin arms pressing down as though in breast-feeding signify abundant procreative and nurturing capacity. This is the fecund goddess as lifegiver. (World History Archive/Alamy)

The answer that seems the most consistent with all the facts is that the practices of the Cro-Magnons included, to begin with, a religio-aesthetic impulse, the celebration of a sense of kinship and interaction between animal and human spirits, which Rachel Levy calls “a participation in the splendour of the beasts which was of the nature of religion itself.”A* But there seem to have been magico-religious purposes as well—attempts to control events. That there were specialists among them who were magicians (or even priests) seems beyond doubt. A vivid mural in the cavern of Les Trois Frères shows a masked man, with a long beard and human feet, who is arrayed in reindeer antlers, the ears of a stag, the paws of a bear, and the tail of a horse, and probably represents a well-known figure in primal communities, the shaman, a person who is especially attuned to the spirit world and called upon to deal with it on behalf of others. Whether or not the shamans were the actual artists, they probably led in ceremonies that made magical use of the paintings and clay figures. Just as in primal cultures of today it is believed that an image or a picture can be a magical substitute for the object of which it is the representation, so the Cro-Magnons may have felt that creating an image of an animal subjected it to the image maker’s power. The magical use made of the realistic murals and plastic works of the Paleolithic era is suggested in several clear examples. In the cavern of Montespan there is a clay figure of a bear whose body is covered with representations of dart thrusts. Similarly, in the cavern of Niaux, an engraved and painted bison is marked with rudely painted outlines of spears and darts, mutely indicating the climax of some primeval hunt; evidently the excited Cro-Magnon hunters (gathering before the hunt?) ceremonially anticipated and ensured their success by having their leaders (shamans or priests?) paint representations of their hunting weapons upon the body of their intended quarry, so vividly pictured on the cave’s wall.

The Fecund Goddess-Mother

Another motif quite different from magic for the hunt appears in Upper Paleolithic paintings and carvin...