![]()

THE CONTEXT OF SOCIAL WORK RESEARCH | | 6 THE FUNCTIONS OF RESEARCH IN SOCIAL WORK 11 CONTROVERSIES IN THE HISTORY OF SOCIAL WORK RESEARCH 18 THE PROFESSIONAL MANDATE 20 TRENDS THAT SUPPORT RESEARCH UTILIZATION 23 RESEARCH IN PROFESSIONAL SOCIAL WORK PRACTICE |

For more than a century, social workers have been transforming our society. Social work interventions doubled the number of babies who survived in the early twentieth century, helped millions out of poverty from the Great Depression to today, and assisted people with mental illness through de-institutionalization, aftercare, treatment, and advocacy. Today our society faces urgent, interrelated, and large-scale challenges—violence, substance abuse, environmental degradation, injustice, isolation, and inequality. Today we need social workers’ unique blend of scientific knowledge and caring practice more than ever.

American Academy of Social Work & Social Welfare (n.d.)

People generally become social workers because they want to have a positive impact on social conditions in order to improve the lives of others. Impact comes from the commitment to make change, and the knowledge and skills to put that commitment to use. Social work history is rich with examples of committed individuals informed by knowledge and skill.

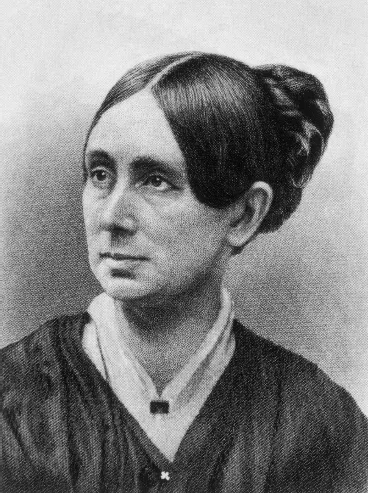

Dorothea Dix, for example, was a pioneering social worker who used research to make an enormous impact in the area of mental health. In 1841, she volunteered to teach a Sunday school class of 20 women inmates at the Cambridge, Massachusetts, jail. After the lesson was over, she went down to the lower level of the building—the dungeon cells. This was where the “insane” were sheltered. She saw miserable, wild, and dazed men and women chained to walls and locked in pens. They were naked, filthy, brutalized, underfed, given no heat, and sleeping on stone floors.

This visit moved Dix to start a campaign to have stoves placed in the cells and to fully clothe the inmates. She also began to study firsthand the conditions for people with mental illness throughout the state. She traveled from county to county, gathering evidence to present to the Massachusetts legislature as the basis for laws to improve conditions. She eventually visited states all over the nation, systematically gathering evidence and making presentations to lobby for the establishment of state-supported institutions for those suffering from mental illness. The first state hospital built as a result of her efforts was located in Trenton, New Jersey. The construction of this hospital was the first step in the development of a national system of “asylums”—places of refuge. Proponents argued that putting people in asylums would be more humane and cost effective than the existing system.

Research continues to impact our society’s approach to mental illness. By 1955 there were 560,000 people in mental hospitals throughout the United States. The institutions themselves had become overcrowded, abusive, and in need of reform. Social workers again used research to convince state legislators that mental hospitals were ineffective treatment facilities. They used interviews with patients and family members to document abuses. They argued that releasing people from mental hospitals would be more humane and cost effective than the existing policy of institutionalization.

In 1843 Dorothea Dix made the following plea to the Massachusetts legislature: “I tell what I have seen—painful and shocking as the details often are—that from them you may feel more deeply the imperative obligation which lies upon you to prevent the possibility of a repetition or continuance of such outrages upon humanity.”

As a result, beginning in the mid-1960s, many mental hospitals were closed in favor of community treatment models. Although community treatment is promising, it has led to an increase in homelessness and mass incarceration among adults with mental illness. Research continues today on the effectiveness of community-based treatment and enhancements such as peer and family support models, as well as jail diversion programs, have been implemented. Researchers play a major role in our understanding of mental illness and in the improvement of services, and hence outcomes, for this population.

This book was written to help social work students develop the research knowledge and skills needed in order to have a positive impact on social work practice and social conditions. As a social worker, you will need to answer many fundamental questions: Did I help the individual, couple, or family I worked with? What types of interventions are most likely to lead to positive change? Who is not receiving social work services even though he or she is eligible for such services? What interventions are the most cost effective? What evidence do I need in order to obtain or maintain funding for a social program? What information do I need to provide policy makers with so that they might support change that will help people in the community? To answer these questions, you will need knowledge and skills in research. The realization that research is vital to social work practice is not new, and the need for research has been demonstrated over and over again, as illustrated throughout this book.

Before we begin to develop research knowledge and skills, however, we must address the one question that is on the minds of so many beginning social work students: Why? Why do I need to learn research? To address this question we present you with an open letter in Exhibit 1.1. We continue to address this question in this chapter by briefly examining the function of research in social work, the history of research in social work, the struggles the profession has overcome, and the opportunities and challenges that lie ahead. Overall, this chapter is devoted to helping you to achieve an appreciation for the place of research in social work and to increase your knowledge of the infrastructure that has been developed to support social work research. The remaining chapters are geared toward helping you develop the research knowledge and skills that will enable you to fulfill your dream of making an impact.

EXHIBIT 1.1 •

A Letter to Students from the Authors

According to an old maxim, “What goes around comes around.” In fact, this happened to me. I took my first policy class when I was a first-year MSW student. I wanted to be a therapist. After a week I (foolishly) asked my professor, “Why do we need any of this?” He looked pained and proceeded to tell me that policy was “the rules” and that those rules would determine what services I could provide and to whom, as well as what funding and access would be available for my “therapy.” I didn’t get it at the time.

Now I am teaching research. One evening, one of my MSW students looked frustrated. I asked if there was something she didn’t understand. “No,” she answered, “I just don’t see why I’ll ever need this.” I am sure I made the same pained expression that my policy professor had made 30 years earlier. For drama, I also clutched my heart. But she was serious and did not mean to induce cardiac arrest. In fact, she wasn’t asking a question; she was honestly stating her feelings.

And so, I was sure I had failed her—not her grade, but her education. Hadn’t I given the “Why you need research” lecture? Hadn’t we examined fascinating research designs and crucial outcome studies? Hadn’t we discussed research ethics, literature reviews, critical analyses, statistical testing, and outcome evaluation? We had … and yet the question had remained.

I came to realize that the student didn’t doubt the importance of research. Rather, she doubted the relevance of research for her. She was sure that SHE would never knowingly do research, just as I was sure 30 years earlier that I would never (knowingly) do policy analysis (or teach research). Foolish me, and probably foolish her.

I guess I need to make my case again. How can you be a clinician, a therapist, an advocate for rape victims, a worker in a domestic violence shelter, a youth counselor, or any other direct service worker without developing research skills? It would be nice to think that we taught you everything you needed to know in the social work program. Too bad—we didn’t. When I was a therapist, I was seeing a client for marital counseling. I had learned a lot about family systems and marital counseling. One day my client told me that his father had sexually abused him as a child. My first thought was, “My program never taught me about sexual abuse of boys by their fathers. What should I do?” I needed to know the developmental impact of this kind of sexual abuse. What kinds of treatments were likely to be effective? How great was the risk of suicide? Should I explore and reflect the client’s past feelings, or should I teach avoidance and compartmentalization? I was very glad—and relieved—that I knew how to access the research literature. Other people’s research made my work a lot less anxiety provoking, for both my client and for me.

Good social workers care about what happens to their clients. Yes, using effective treatments and validating results is part of the NASW Code of Ethics. However, good social workers don’t want to be effective just because the Social Work Code of Ethics demands it. Instead, they want to be effective because they CARE. Research helps you and your clients to see what you are accomplishing (or not accomplishing) as a result of services provided.

I recently heard about an exciting new treatment: eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy (EMDR). It really works. At least, that’s what they tell me. But for whom, and in what context? Does it work equally well for men and women, adolescents and preadolescents, Hispanics and African Americans? Decisions, decisions, decisions … so many decisions to make as part of providing services to your clients. Is it better to use it in individual or group treatment? How many sessions does it take? Sometimes the research literature provides answers; sometimes it doesn’t. You need to know how to get the evidence you need to make treatment decisions. You can be a “force” for evidence-based practice at your agency. We do things because it has been demonstrated that they work. OK, sometimes we try something innovative if there is enough theory or evidence to suggest it’s worth a try. However, we don’t continue to do the same thing using up scarce resources if it doesn’t work. You have to know one way or another.

Money. Money. Money. Why does it always come down to money? You want money so you can continue your program. You want money so you can expand your services or offer new services. You can get the money, but you have to know how (and who) to ask. These days, funders don’t give money easily. You have to get it the old fashioned way, by demonstrating that you need it and will use it wisely. Demonstrate that people want, need, and will use your service. Demonstrate that what you want to provide is effective. Demonstrate that you put the money already given you to good use. You demonstrate these things through program evaluation, a.k.a. research.

Sometimes people say some strange and hurtful things in the name of “truth.” Sometimes they do this because they want to stop what you are doing. I’m referring to comments like, “Most people on welfare cheat the system.” Going further, in some cases they actually come up with research to support their claims. You need to know enough about research to show them (or politicians/funders/your community) the error of their ways, or of their method of obtaining data, or of their statistical procedures, or of their (false) conclusions. First you have to “smell” it, then point it out, then get rid of it.

OK, if you don’t want to “walk the walk,” at least learn to talk the talk. SOMEONE will do research. Do you want to be able to explain your program and its objectives in a language that a researcher understands, and do you want to understand the language of the researcher to be sure that what is being done in research is appropriate. Bilingual is good.

So, maybe you won’t ever have to do research or policy analysis. Or, maybe you will. Maybe you think you’ll be a case manager or a therapist for the rest of your life. I thought that. Funny, though, things change. You may become a supervisor, an advoc...