eBook - ePub

European Literary History

An Introduction

- 382 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

European Literary History

An Introduction

About this book

This clear and engaging book offers readers an introduction to European Literary History from antiquity through to the present day. Each chapter discusses a short extract from a literary text, whilst including a close reading and a longer essay examining other key texts of the period and their place within European Literature. Offering a view of Europe as an evolving cultural space and examining the mobility and travel of literature both within and out of Europe, this guide offers an introduction to the dynamics of major literary networks, international literary networks, publication cultures and debates, and the cultural history of 'Europe' as a region as well as a concept.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access European Literary History by Maarten De Pourcq, Sophie Levie, Maarten De Pourcq,Sophie Levie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literatur & Literaturkritik. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Antiquity

1 Introduction

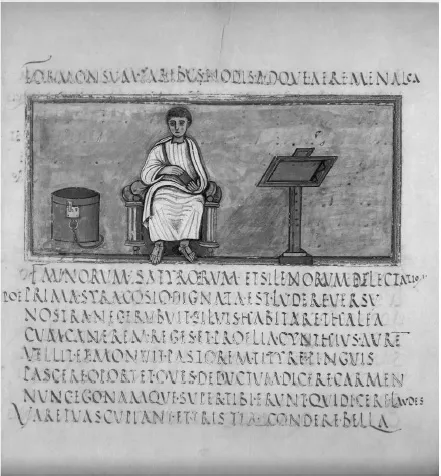

Figure 1.1 Virgil, depicted in a manuscript of the Aeneid, c. 500 CE, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. Lat. 3867, f. 104r

“I sing of wars and the man” (arma uirumque cano). So begins Virgil’s Aeneid, a Latin epic written at the height of the Roman Empire when ancient Rome was being governed by its first emperor, Augustus, who came to power in 27 BCE. This epic of some 10,000 lines in Latin by the author Publius Vergilius Maro (Virgil, also spelled Vergil in English) tells the story of “the man” Aeneas, the legendary Trojan warrior who left his home town of Troy, in modern-day Turkey, after it had been destroyed by the Greeks, and came to Italy to found a city from which the future Rome eventually would rise.1 The Aeneas of Virgil’s epic never founds this city (the epic ends with Aeneas killing his local Italian enemy, Turnus, on the battlefield), but no matter. This is the epic that came to define Rome; the successor to the Greek epics of Homer and a work that would come to shape European literature from Virgil’s own day up to and including contemporary literature.

In the first part of this book, dealing with classical antiquity,2 we present some of the major literary works from the ancient world, we discuss what literature means in this period, and we consider the impact of classical literature on European literature and thought. We aim to show how these texts, like Virgil’s Aeneid, can be viewed as “European” despite being written at a time when Europe as we know it today did not exist. The “ancient world” covered a vast period of time from the beginning of recorded history (several thousand years before the common era) up to the early Middle Ages, although those texts that we typically classify as ancient literature generally date from the eighth century BCE until the fifth century CE. Spanning several hundreds of years, this period of history featured changing geographical landscapes as emerging powers claimed new territory for their empires, which at times incorporated not only European regions like Italy and Greece but also areas in Asia and in Africa.

This was the world that “Europe” was part of and the literature that it produced can be viewed as a reflection of this changing political, cultural and geographical landscape. As power shifted from one empire to another, so did Europe’s cultural centres, most notably from Athens (Greece) to Alexandria (Egypt) and to Rome (Italy). As each new cultural centre claimed power and influence over its rivals, the authors within those centres sought to respond to these changes in their literary works. When we study texts from the ancient world, therefore, we can see these authors engaging directly with the literary works of their predecessors and contemporaries. This direct and deliberate engagement with other texts is what is known as “intertextuality”*, and it is an important concept for all European literature. No literary text exists in a vacuum, but it builds on and, consciously or unconsciously, responds to previous texts: the ancient Greeks reacted to earlier Near Eastern genres, the Romans to Greek literature, and later European literature to the texts that survived from Greece and Rome.

Singing of arms and men

Ancient literature can be divided predominantly into two different types: works of prose and works of poetry. Ancient prose works cover genres such as historiography, rhetoric, and the ancient novel (all of which are covered in this section), whilst poetic works include lyric poetry, drama, and epic. For those ancients who wrote poetry, this also meant writing in different metres*: lines of Greek and Latin that contained a set number of syllables that were either “long” or “short” and “heavy” or “light” to create a specific rhythmic effect. Such works were often intended to be read aloud – or even performed – since the sound of the text mattered as much as its content. When Virgil claims to “sing” about arms and the man, therefore, he means this literally: it was the epic poet’s job to proclaim the deeds of heroes*, and this idea of singing is rooted in the very origins of epic. For before the written word was the spoken, and long before the epics of Homer (our earliest extant epics) acquired written form, they were performed by travelling bards* who entertained the crowds they met on their journeys.

We will return to this idea of “orality” in a moment, but for now let us focus on the hero of Virgil’s epic, Aeneas, and his own European journey – from Troy in the East to Rome in the West – as a refugee in search of a new home.

I sing of wars and the man, fated to be an exile, who long since left the land of Troy and came to Italy to the shores of Lavinium; and a great pounding he took by land and sea at the hands of the heavenly gods because of the fierce and unforgetting anger of Juno. Great too were his sufferings in war before he could found his city and carry his gods into Latium. This was the beginning of the Latin race, the Alban fathers and the high walls of Rome.3

In the first few words of this epic, Virgil tells us that he intends to focus on wars (arma) and on a man (uir), Aeneas. But despite the fact that the emperor Augustus claimed direct lineage from him as the supposed founder of the Roman race, Aeneas was not by any modern definition “European”. According to tradition he was the son of the goddess Venus and a mortal man, Anchises, who came from Troy, a city located in modern-day Turkey.

This “fact” already problematizes our understanding of what would have constituted a European identity in the ancient world, but first we need to recognise that at this time there was no concept of a shared European identity beyond the basic and often vague recognition of the continent of Europa (so the term was in use and most probably coined in antiquity), alongside Asia and Libya (also known as Africa), and an equally vague, cultural distinction between East and West, with the “East” being made up of ever-changing peoples from Asia and also Egypt. People in the ancient world, therefore, whilst they would have been culturally and politically aware of other states, would not have viewed themselves as “European”, but rather would have identified with the geographical location in which they were born and raised. More often than not this would have been a place rather than a country: thus Athens as opposed to Greece; or Rome as opposed to Italy. Ideologically*, therefore, a person’s sense of self in the ancient world was most frequently defined in terms of what it meant to be “Athenian” or “Roman”. This process of self-definition was put into practice by comparing oneself to the people with whom one came into contact. A repeated pattern that we see in ancient Athens, for example, was the desire of Athenian citizens to define themselves in relation to their Spartan as well as Persian enemies, viewing themselves as the cultural counterpart to both of them.

When the legendary Aeneas makes his journey from Troy in the East to Italy in the West (the voyage referred to in lines 1–3 previously), therefore, he is not simply traversing his way across what was – to Virgil’s audience* – the geographical space of Augustus’s empire. His journey was a symbolic one, a statement that Rome had become the cultural hub to which all peoples should gravitate. This claim to cultural superiority is also suggested by the opening lines of Virgil’s epic. For in lines 5–7, Virgil tells his audience that the Aeneid is an epic about foundation and succession. This idea of foundation and succession operates on two levels. First, Aeneas is presented as the founder of the Roman race, with Augustus as his direct descendent. Second, Virgil presents his epic both as a foundation text for Rome, in its guise as the new cultural and political centre of the world, and as the successor to the much-revered Greek epics of Homer, which stand at the beginning of ancient Greek literature: the Iliad and the Odyssey. Virgil alludes to both these works in the opening words of his epic: to the “wars” that Aeneas will fight, which recall the battles in Homer’s Iliad, and to the “man”, Aeneas, who will follow in the footsteps of Odysseus, as he voyages across the Mediterranean sea, searching for his home.

Thus “wars and the man” are defining features of Virgil’s epic and both are inextricably tied to the idea of foundation. The Latin verb for “to found”, condere, that Virgil uses in line 5 illustrates this tie well. For as well as meaning “to found”, this verb can mean “to compose” – thus also referring to Virgil’s composition of the Aeneid – and “to strike”, referring to the physical act of (e.g.) plunging a sword into the heart of an enemy in battle. This is, in fact, how Virgil uses this verb at the end of his epic, when he describes how Aeneas kills his enemy, Turnus. This, then, was foundation, achieved by a man through war and embodied in poetry.

Virgil’s epic, at both its start and its end, illustrates the role that war plays in the composition and content of ancient literature. This is especially clear to see in literary genres such as epic* and historiography, which frequently address issues of war, but its presence also extends to love poetry*, where poets could present themselves as soldiers battling for the object of their affections. This obsession with warfare is in part a reflection of the times in which these authors were writing. War was an integral part of people’s lives in ancient times and throughout most of European history. War, and by reflex literature, was predominantly the domain of “the man” in the ancient world, but it would be wrong to presume that women played no role in ancient literature. Whilst the position of women in society varied across the ancient world in accordance with different time periods and cultures, not only were women influential in political affairs in, for example, Rome and Egypt, but texts have survived that were written by women in Greece and Rome.4

Women also play a prominent role as characters within literary texts of the ancient world. These roles are, of course, most frequently assigned by male writers, with the result that the depictions of these women tend to follow distinct stereotypes: they are depicted as the object of the male gaze; they are cast in the domestic roles of mother, daughter, and wife; or they buck these trends and, as a result, are depicted as “problematic”. Nevertheless, ancient literature has created many powerful women, such as Helen, Medea, and Dido, whose longevity and influence are evident throughout European literature.

Nor should it be forgotten that according to Greek mythology*, the personification of Europe was a woman, the princess Europa. Like many a mythological female in the ancient world, Europa’s story is one of male aggression followed by divine reward. According to the most common tradition, Europa was the daughter of the king of the Phoenician city of Tyre. She was abducted by the god Zeus, who disguised himself as a bull and tricked her into climbing up onto his back when she was playing with friends by the seashore. Zeus whisked Europa away across the sea to the Greek island of Crete – so completing another mythical journey from East to West – and after raping her he gave her as a “reward” (or rather recompense) semi-divine offspring which would rule over Crete. The irony of an “Eastern” woman from Tyre giving her name to what we now call Europe affirms the malleable nature of boundaries – both geographical and cultural – in the ancient world. And it is a reminder that much ancient literature has the idea of travel and transition at its heart. The myth of Europa as the source for the name “Europe” is one of several aetiological* (that is “origin”) stories concerning the origin of this world. Such stories captivated ancient writers for millennia, and the re-workings of these tales* are a key aspect of ancient, especially poetic, works.

The literature produced in the ancient world was, therefore, affected by a number of factors: shifting cultural centres and geographical boundaries, wars, and the literary output of previous generations. Yet despite these shifting boundaries and the long stretch of time, it is possible to chart the progression from one cultural powerhouse to the next, and to see within this complex world the development of distinct literary genres, as well as the transition of literature from orality to the written word, and from poetry to prose.

From singing songs to writing prose

Ancient Greek literature is usually divided into four time periods that coincide with four recognisable periods in ancient history: the archaic Greek period (ca. 800–500 BCE); the classical Greek period (ca. 500–300 BCE); the Hellenistic period (ca. 300–30 BCE), when Greek culture (referred to as “Hellenistic”) spread over the whole Mediterranean world; and the Roman Imperial period (ca. 30 BCE to 450 CE). Latin literature, of course, started well before 30 BCE, when Rome conquered the last remaining Hellenistic kingdom, Cleopatra’s Egypt. It can be subdivided into three periods: the preliterate period (750–250 BCE); the Republican period (250–30 BCE); and the Imperial period from 30 BCE until the end of the western Roman empire, usually dated around 450 CE. At the transition from the Republican to the Imperial period falls the Golden Age of Latin literature wit...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of contributors

- General introduction

- Part I Antiquity

- Part II Middle Ages

- Part III Early modern period

- Part IV The long nineteenth century

- Part V The modern era

- Bibliography

- Index of terms

- Index of authors and works