eBook - ePub

The Politics of Bureaucracy

An Introduction to Comparative Public Administration

- 390 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Written by B. Guy Peters, a leading authority in the field, this comprehensive exploration of the political and policy making roles of public bureaucracies is now available in a fully revised seventh edition, offering extensive, well-documented comparative analysis of the effects of politics on bureaucracy.

Updates to this edition include:

- All new coverage of public administration in Latin America and Africa, with special attention paid to the impact of New Public Management and other ideas for reform;

- An examination of the European Union and its effects on public policy and public administration in member countries, as well as an exploration of the EU as a particular type of bureaucracy;

- A renewed emphasis on coordination and the role of central agencies;

- A thorough assessment of 'internationalization' of bureaucracies and concerns with the role of international pressures on domestic governments and organizations in the public sector;

- Coverage of the wide-ranging impacts of the 2008 economic slowdown on public bureaucracies and public policies, and the varied success of governmental responses to the crisis.

Drawing on evidence from a wide variety of political systems, The Politics of Bureaucracy, Seventh Edition, continues to be essential reading for all students of government, policy analysis, politics, and international relations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Politics of Bureaucracy by B. Guy Peters in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Public Administration and Governing

The Modern Public Sector

The Growth of Government

The Growth of Administration

Countertrends in Government Growth

Summary

I began the first edition of this book with the statement that government has become a pervasive fact of everyday life and that, in addition, public administration has become an especially pervasive aspect of government. This statement remained true despite the long terms in office of a number of conservative governments in many industrialized nations (Ronald Reagan and the two George Bushes in the United States, Margaret Thatcher, John Major and then David Cameron in the United Kingdom, Helmut Kohl and then Angela Merkel in Germany). These governments were joined later by right-of-center governments in unlikely places such as Denmark and Sweden. Despite their rhetoric, these governments were never able to reduce the size and influence government to any significant degree.

Many contemporary governments from the political left are not the same types of social democrats as in the past. Most of these governments have accepted many of the same premises about the need to reduce the size of government, and have made concerted attempts to reduce the role of government in the lives of their citizens. Social Democratic governments all over Europe, with the possible exception of France, have adopted some of the same rhetoric of the “Third Way,” albeit in varying degrees. Government is not the enemy that it was, and is, to some conservatives but neither is there much acceptance of the “tax and spend” behavior of left governments in the past, even in the Scandinavian governments.

What is true for the industrialized democracies is especially true for countries of the former communist bloc, and for many developing countries in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The political systems in central and eastern Europe experienced almost total transformations of their governmental structures to reduce the intrusiveness of government and to permit greater personal freedom – economically as well as politically (see Verheijen, 2007). These changes in values have been accompanied by radical transformations of the public sector. The changes included numerous public enterprises being privatized and public employment being downsized.

The countries of Africa, and especially Latin America, experienced significant pressures from international donor organizations to reduce the size of the State and utilize more market mechanisms. While following that “Washington Consensus” for some years, many countries have returned to more interventionist styles of government. In the extreme, countries such as Venezuela and Bolivia have adopted a limited form of socialism, while others such as Uruguay have returned the State to a more central position.

Despite the best efforts of political leaders, however, an enhanced role for the public sector appears to persist in many countries, and in some cases that role even continues to increase. Leaders of governments have usually found government more difficult to control than they had believed before taking office. This chapter will attempt to document briefly the generalization – if indeed any documentation is required – that the public sector is difficult to control and even more difficult to “roll back.” Indeed, as the state is rolled back in some ways it almost inevitably must “roll forward” in others. Privatizing industries – especially public utilities – will mean that those industries will have to be regulated in some way to ensure that the public is treated fairly (Majone, 2005). The large-scale privatization occurring in Eastern Europe has meant that legal principles like property rights and contracts, as well as regulatory mechanisms, must be created by government. In other countries, where the central government has assumed a smaller role in society, lower tiers of government have accepted enhanced roles, and in some cases whole new tiers of government have been created (Horvath, 2000; Loughlin, 2001). In all of these cases, governments remain involved in the economy and society, just in less obvious ways.

The growth and contraction of government have become objects of substantial scholarly research (Tanzi and Schuknecht, 2000). Attempts to change the size of government have also become a rallying cry for political activity, whether the attempt is to expand or to contract the public sector. Any number of explanations have been advanced for the growth and persistence of the public sector. Likewise, the expansion of the public bureaucracy has been conceptualized as either a by-product of the general growth in the public sector or as a root cause of that growth. Further, if government is not able to decrease its size and its influence in a society, the blame is often placed on an entrenched public bureaucracy. For example, the expanding role of the European Union in the daily lives of the citizens of the now 27 member countries is often phrased in terms of expansionary ideas of the “Eurocrats” in the European Commission (Trondal, 2010).

On the other hand it is important to place contemporary public administration in its political and intellectual context, and the increased concern about the magnitude and impact of government remains an important factor in shaping the current debate about the public sector, and about public administration. At home, governments seeking to provide better and more equitable services to the public must also be conscious of the resistance of the public to taxation. Internationally, the international financial community is skeptical of a large public sector and exerts an influence through the bond and currency markets, including in industrialized democracies such as Greece, Spain, and Portugal.

The Modern Public Sector

The above paragraph was written as if the “size of government” could be clearly and unambiguously measured (see OECD, 2007). In fact, it is a fundamental feature of contemporary government, especially in industrialized societies, that the boundaries between government and society – between what is public and what is private – are increasingly vague. As a consequence of that imprecision, any attempt to say unambiguously that government is growing or shrinking is subject to a great deal of error and misinterpretation. For example, by some measures the government in Russia would be larger in 2000 than it was prior to the collapse of the former system because taxes are now higher as a proportion of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) than under communism (Stepanyan, 2003).

Further, the imprecision in measuring the size of the public sector can be utilized politically to make arguments about the successes or failures of incumbent governments to exercise proper control over the public sector. In an era of skepticism about the public sector and resistance to taxation, the issue of controlling the public sector is often important politically (Van de Walle and Bouckaert, 2003). Opposition politicians find it very convenient to argue that their opponents have let the public sector “run amok” and can usually muster some evidence to support that assertion. Likewise, incumbent politicians can gather their own evidence to demonstrate that they have indeed been good stewards of the public purse.

Several examples of the difficulties in measuring the magnitude of the public sector may help to clarify this discussion. One obvious example is the role of the tax system in defining the impact of government on the economy and society – an impact that is not adequately assessed by most measures of the size of government. In the United States, for example, subsidies for housing through the tax system (primarily through the deductibility of mortgage interest and local property taxes) exceed direct government expenditures for public housing by more than 200 percent; this despite numerous attempts at “tax reform” (see Farley and Ellis, 2014). Likewise, although the United Kingdom has had a substantial public pension program, tax relief for private pensions schemes exceeds £3 billion (but see Wildavsky, 1985). Similar tax concessions are available to citizens of the majority of industrialized countries, with some of the highest nominal tax rates accompanying some of the most generous tax concessions. All of these tax loopholes influence economic behavior and amount to government’s influencing the economy and society just as if it taxed and spent for the same purposes. Tax concessions are not, however, conventionally counted as part of the size of the public sector, as expenditures for the same purposes would be.

Government loans are another means through which government can influence the economy without ostensibly increasing the size of government. In the majority of industrialized countries governments make loans to nationalized industries that often are not repaid; these defaulted loans do not always show up as an item of public expenditure (Stanton, 2001). Even loans to individual citizens, for example to farmers, or to small businesses, often are not counted as expenditures, given the assumption that eventually they will be repaid. The involvement of government is even more subtle when, as in the United States, governments offer guarantees for private loans to companies in financial difficulty or to students who want to go to college. Such arrangements involve the actual expenditure of little or no public money but, again, produce a significant effect in the economy.

Not only do expenditures and other uses of financial resources fall on the boundary between the public and private sectors, but organizations do as well. There has been a significant increase in the number of quasi-public organizations in most countries during the postwar era. In order to provide organizations with greater flexibility in making decisions, or to subject them to greater market discipline, or to protect them from potentially adverse political pressures, or simply to mask the true size of government, organizations have been created that straddle the public–private fence. In some instances these organizations are created anew as government enters a policy area for the first time – for example, the Corporation for Public Broadcasting in the United States. In other instances organizations that existed previously as a part of government are “hived off” to a quasi-independent status, as many of the numerous Next Steps agencies in the United Kingdom (James, 2003). That agency model has since been copied in a large number of other countries (Verhoest and Van Thiel, 2012).

In addition to the obvious measurement problems these quasi-governmental organizations create, they give rise to even more important problems of accountability. As they have been divorced from direct control by government to some extent, the conventional political and legal means for enforcing accountability (see Chapter 8) may no longer be applicable (Considine, 2001). The result is that these organizations (and the politicians who are responsible for them) have opportunities for abuse of powers. Further, given that they are at once public and private, the average citizen may find it difficult to ascertain who really is responsible for the services they provide. Somewhat paradoxically, as governments have sought to appear smaller and more efficient, the resultant confusion and perceived lack of accountability may cause even greater harm to their reputations with the public.

Public Spending

Although we now can see that it is difficult or impossible to measure the magnitude of government definitively, we can still gain insight into the changes that have taken place in the role of government by examining figures for public expenditure. This variable is the most widely used measure of the relative size of government and represents perhaps the most visible portions of governmental activity. A better insight about the size of the public sector can be found in the relationship between government expenditure and GDP, a standard measure of all the marketed goods and services produced in an economy.

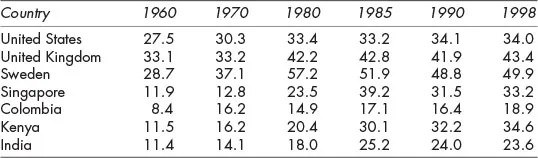

As seen in Table 1.1, there are marked differences among nations in the proportion of GDP devoted to public expenditure. The most obvious differences are between the less-developed and the industrialized nations. Even the less-developed country with the highest level of public expenditure (Kenya) spends much less as a proportion of GDP than does the United States, which spends the least among the three industrialized countries in the table. Of course, a sample of only seven countries is prone to great error, but similar findings probably would be present were there a much larger sample of nations. In addition, there are differences among the industrialized countries and among the less-developed countries. For instance, Sweden spends over 80 percent more in the public sector as a proportion of GDP than does the United States.

Table 1.1 Public Expenditure as a Percentage of Gross Domestic Producta

Sources: United Nations, Statistical Yearbook (New York: United Nations, annual); United Nations, Yearbook of National Accounts (New York: United Nations, annual); World Bank, World Tables (Washington, DC: World Bank, annual).

Note

a Gross Domestic Product at market prices.

a Gross Domestic Product at market prices.

In addition to the differences among the countries, the rate of increase in public expenditure appears substantially higher in the less-developed countries than in the industrialized countries. India has almost quintupled the percentage of GDP devoted to public expenditure over the 38 years from 1950 to 1988, while Colombia has more than doubled the percentage during that time. Kenya almost tripled its percentage of GDP in the public sector from 1960 to 1990, although the increase has virtually stopped. The rate of increase in spending has been almost as rapid in Sweden as in the less-developed countries. The rate of growth of public expenditure has been much more modest in the other two industrialized countries, and has slowed or stopped in Sweden. A major exception to the increasing size of the public sector has been in Singapore, a “newly industrializing country,” where the public sector has increased very little and there has been a great deal of emphasis on ensuring a good business climate for its rapidly growing private sector (Evans, 1995).

Part of the reason for the relatively lower rate of public expenditure in the less-developed countries is that so much of their GDP comes from agriculture and especially subsistence agriculture, as is apparent in Table 1.2. This means that there are fewer “free-floating resources” in the economy that are readily taxed. The other way of saying that is there are fewer tax handles for government to use in extracting resources. A cash transaction is easier to tax than if someone is simply growing his or her own crops in order to eat, or is trading by barter. If we calculate the level of public expenditure in relation to the secondary and tertiary sectors of the economy (manufacturing and services, respectively), we get a somewhat different picture of the rate of public expenditure in the less-developed countries. Using this calculation, Ta...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright page

- Table of Contents

- About the Author

- 1 Public Administration and Governing

- 2 Political Culture and Public Administration

- 3 Recruiting Public Personnel

- 4 Problems of Administrative Structure

- 5 The Politics of Bureaucracy

- 6 The Bureaucracy and Political Institutions

- 7 The Politics of the Budgetary Process

- 8 The Politics of Administrative Accountability

- 9 Administrative Reform

- 10 The Politics of Public Management

- Bibliography

- Index