![]()

1

The Strategic Police Leader

The New World of Police Leadership

The core goals of modern policing are clear: prevent crime, increase community safety and security, build public trust and confidence in the police, and do all of this in fair and lawful ways. These objectives were part of the mission when I joined the Metropolitan Police Service in London as a cadet in 1984, and they remain the core mission of policing in a democracy today.1

While these core goals have remained consistent, the pace of change since the mid-1980s for everyone in law enforcement has been bewildering. The social service function has taken on a more significant role as funding for other community agencies has diminished. Yet crime fighting remains, in the minds of officers and the public, a core mission of the police.

If you are a serving officer reading this, then keeping people safe, either from crime or other societal harms, is likely why you joined the job. You have experienced the joys, frustrations, boredom, fear, and exhilaration of being a police officer. You and your family are acutely familiar with the commitment and desire to make a difference. But that core mission—actually making a difference—seems harder these days, especially after promotion. The new world of police command takes place in the spotlight. Police leaders, and especially mid-level commanders, are under more scrutiny than ever before. The job has more accountability, and feels more urgent. Unfortunately, these trends can drive a short-termism and a risk aversion that is harmful to good decision-making and, ultimately, public safety.

Police leaders, and especially mid-level commanders, are under more scrutiny than ever before.

While this modern world has created greater accountability, many commanders lack experience in implementing successful crime reduction. Their previous policing roles were often tactical and oriented to discrete cases and solving individual calls for service. This isn’t to negate that wealth of experience, but rather to realize that being a commander requires a skill set that is fundamentally different from frontline policing. It is rarely taught and difficult to acquire prior to actually being in command.

I’ve been lucky enough to consult and work with police commanders from five continents, and there are some commonalities worth mentioning. They might have been promoted on the basis of passing an exam and demonstrating some legal knowledge, or when they demonstrated excellent on-the-ground, incident-driven presence. As new commanders quickly learn, these experiences do not necessarily prepare one for the new craft of policing: working with partners and demonstrating strategic leadership—directing policies and programs. Because agencies have limited training budgets, most area commanders are thrust into command with little preparation.

There is also a general assumption that area commanders know how to ‘do’ crime reduction, simply by virtue of having been in the job for some years and earning promotion. They may have been detectives, worked in the property or personnel office, or been the liaison to the local counter-terrorism center. The police service often thinks that these disparate jobs qualify someone to be an area commander skilled in planning and organizing burglary and vehicle crime reduction campaigns. This is akin to asking a doctor with expertise in tropical diseases to be the chief surgeon at an inner-city trauma unit. Some basic ideas are common, but in general the previous experiences are of limited value in the new role (as Tracey Thompson explains in Box 1.1).

If this feels familiar, then don’t worry—this book has been written for you. Of course, there is no way to predict your exact circumstances precisely; however the aim of this book is to provide a general evidence-driven guide to the challenge of reducing crime in your community.

Box 1.1 Leaders Should Not Take for Granted the Mana

“Although I had 22 years of policing under my belt, this in no way prepared me for the responsibility I faced when I stepped into an area command role. I’d been a technical expert in various police roles, but as area commander it was not as important to know a lot about one thing, but instead to know a little about everything. I needed to be informed enough that I could work with the many audiences I was now required to engage with both internally and externally.

The reality was that for the first few months of my tenure the ‘people’ aspect of my role seemed to take precedence. Staff were trying to get a sense of my priorities and it was important to me that I was a visible and supportive leader. I do not take for granted the mana (our Māori word for prestige, status, and authority) that comes with this role.

Externally, there was also a high expectation of me from our community. My area has a multi-cultural vibrancy, but also great wealth and age divides. And being Māori, it was important for me to build and maintain strong relationships with our local Iwi (tribe) and Māori community. I therefore had to be dynamic in the way I managed the different needs of our diverse communities.

As I got more comfortable in my role, conversations at our leadership table began to change with more focus on achieving our organizational priorities of crime, crash, and victimization prevention. To do this we have continued to build and maintain strategic relationships with our community and government partners. I’ve learned that leadership is the key to being a good area commander, and it’s a long journey.”

Tracey Thompson is an inspector with the New Zealand Police. She is currently area commander of Kapiti Mana Police in Wellington District.

A Community Harm Perspective

As you move into a more strategic leadership role, you will be challenged to micromanage less and adopt a broader perspective. This includes balancing crime and disorder reduction alongside other community and organizational goals, including police legitimacy. As one police colleague told me: “nothing about my previous service prepared me for being a district captain.”

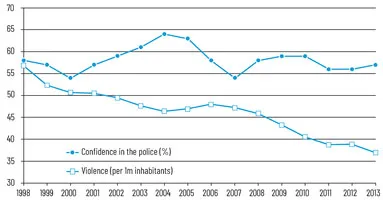

Figure 1.1 Violence compared to confidence in police Sources: Gallup, FBI UCR Crime in the United States

Policing isn’t just about crime. If it were, the police would have reaped a public perception reward for the decades of lowering recorded crime since 1990. Figure 1.1 shows the percentage of American adults who have a ‘great deal’ or ‘quite a lot’ of confidence in the police. Alongside is the violent crime rate per one million inhabitants. While crime has steadily declined, that benefit doesn’t appear to have changed public perception of the police.

Trust and confidence in law enforcement do not stem from just tackling crime. Modern policing is about delivering a service that addresses harm, social disorder, community safety, and reassurance, all in a framework that instills confidence in the police and is procedurally just. The public want their police to not only fight crime but be attentive to their needs: reliable, responsive, and competent. They also want the police to have good manners, and to treat people with fairness.2

I’ve worked with area commanders who are judged by the community as much on their ability to combat late-night noise and traffic problems as reducing violence and murder.

Wherever there is crime, there is frequently also physical and social disorder. In some of the most crime-ridden corners of everywhere from Philadelphia to San Salvador, I’ve worked with area commanders who are judged by the community as much on their ability to combat late-night noise and traffic problems as reducing violence and murder. People worry about crime, but they are also drained by the day-to-day dysfunction in their neighborhoods. While this book focuses on crime, the techniques you will find in here are also useful for dealing with many of these nuisance issues.

A challenge you will certainly face is that others may not share your sense of what is a problem and how to deal with it. With promotion, you will increasingly hear from the mayor, other law enforcement agencies, frontline officers, the police chief, non-governmental organizations, and different factions in the community. You become increasingly exposed to chronic problems that lie beneath the surface of your policing area. You will attend meetings and get briefings that open your eyes to a new viewpoint. You are likely to be more aware of the community’s concerns than most patrol and frontline officers, and you will inevitably become a more strategic thinker (see Box 1.2).

This can clash with the perspective of frontline responders who focus on the immediate and seek out pragmatic solutions that work in the moment. As you develop a sense of the problems you need to address, be aware that other stakeholders may not share your perspective. Their goals and aspirations, and even their feelings about the role of the police in modern society, may be fundamentally different. You will likely have to rely on softer skills, persuasion, and transformational leadership to negotiate with these groups (see Chapter 11).

Box 1.2 Data Fuels a Holistic Approach to Crime Problems

“In policing, we assume that you are immediately competent upon promotion and on arrival in your new role. After all, you’ve been a cop for many years, so your professional judgement will guide you through, right? This belief couldn’t be farther from the truth. When I started as an area commander, vast quantities of detailed information hit my screen with limited explanation. What did it all mean, how was I to decipher it all, and what did I need to do? I was lost in a sea of information with no guidance.

I sought help. I quickly learnt that by sharing crime data with key stakeholders I was able to support a more robust, holistic approach to our crime problems. I used data to focus on not only crime reduction but also building neighborhood cohesion. Before taking an area command, I had never realized how important community and other government partners were in modern policing. Tackling problems together with partnerships provided far wider benefits than I could achieve on my own. In time, communities began to take pride in their area, influencing a reduction in crime and creating a place in which people could have pride.”

Jared Parkin is a superintendent in Dorset Police (U.K.), with responsibility for operational and neighborhood policing in an urban environment.

A Three-Pronged Approach to Crime Reduction

For police officers with a good nose for crime, the move to command can often be challenging. Charles Ramsey, former Philadelphia Police Commissioner, once said, “You think at first it’s just about locking up bad guys, but it’s not. It’s really about making communities safer.”3 I remembered this quote when I was on a ride-along with officers in a busy inner-city precinct. Their captain had a reputation for patrolling and making arrests, yet these experienced cops lamented that their area didn’t feel like it had any kind of a plan to make a dent in crime. They just chased the radio from call to call, without a sense that there was a strategy. While he appreciated the street cop side of his captain, one patrol officer said: “That’s not what he is paid for. That’s not why he gets the big bucks.”

While he appreciated the street cop side of his captain, one patrol officer said “That’s not what he is paid for. That’s not why he gets the big bucks.”

Good street cops have a natural tendency to get into the weeds. It’s not necessarily the best trait for a leader. Without a strategic plan we are left with fire-brigade policing, rushing from call to call yet doing little to address chronic problems strategically. Sir Denis O’Connor served as one of Britain’s most senior police officers (after getting his start on H district in the Metropolitan Police). He refers to much of current policing as ‘schoolboy football.’ If you have ever watched youngsters playing soccer, you will know what he means. They all crowd around the bal...