eBook - ePub

Meaningful Online Learning

Integrating Strategies, Activities, and Learning Technologies for Effective Designs

- 206 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Meaningful Online Learning

Integrating Strategies, Activities, and Learning Technologies for Effective Designs

About this book

Meaningful Online Learning explores the design and facilitation of high-quality online learning experiences and outcomes through the integration of theory-based instructional strategies, learning activities, and proven educational technologies. Building on the authors' years of synthesized research and expertise, this textbook prepares instructors in training to create, deliver, and evaluate learner-centered online pedagogies. Pre- and in-service K–12 teachers, higher education faculty, and instructional designers in private, corporate, or government settings will find a comprehensive approach and support system for their design efforts.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Meaningful Online Learning by Nada Dabbagh,Rose M. Marra,Jane L. Howland in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralCHAPTER 1

Meaningful Online Learning: Theories, Concepts, and Strategies

This chapter provides an overview of online learning, its delivery models, design considerations, and underlying theories and standards for design. It describes the characteristics of meaningful learning and how these intersect with the unique nature of online learning environments.

Online Learning

Distance education has existed since the 1800s, when it took the form of correspondence courses (Simonson, Smaldino, Albright, & Zvacek, 2009). Throughout the 1900s, radio broadcasting and, later, satellite television delivered content to distance students. But the Internet changed everything. With the Internet, online learning became possible.

What is online learning? In its simplest form, online learning might be described as any learning that takes place using the Internet as a delivery system. Precisely how online learning is defined continues to be debated (Lowenthal & Wilson, 2010). Terminology such as online learning, e-learning, distance learning, and blended or hybrid learning are often used interchangeably. Although characteristics of online, e-learning, and distance learning contain some common elements, there is inconsistency in the ways different people use these terms (Moore, Dickson-Deane, & Galyen, 2011). Organizations such as the Online Learning Consortium (OLC) are attempting to develop common definitions to aid practitioners, researchers, and policy makers as the field advances (Mayadas, Miller, & Sener, 2015). Online learning can range from learning environments where individuals work primarily independently, experiencing little or no interaction with an instructor or other learners, to courses where students are highly engaged in interactive learning with the instructor and peers. Here we describe some of the attributes of various types of online learning as presented by the OLC.

The amount of time spent in a physical classroom versus time spent in online activities is a consideration when labeling various types of courses. A web-enhanced course utilizes technology as a minor supplement to traditional classroom activities—usually no more than 20%.

Synchronous distributed courses provide real-time classroom learning experiences to individuals who are off-campus. These courses can allow interaction between students meeting face-to-face with an instructor in a physical classroom and students at a remote location.

Blended or hybrid classroom courses and blended or hybrid online courses retain some face-to-face elements, but a large portion of instruction may take place online. The amount of face-to-face versus online contact is largely determined by individual institutions, who may use blended courses for a variety of reasons, including freeing classroom space to offer more course sections or allowing some flexibility for students.

In contrast to the types of online learning described above, a true online course consists of no face-to-face contact; all learning takes place via the Internet. Removing geographical barriers allows learners to interact with others from any location worldwide. A learning environment that is entirely online may be completely asynchronous, meaning all activities take place when the learner chooses. There may be time constraints on when work must be completed (e.g., one-week learning units, project or discussion forum due dates) but within those constraints the learner can schedule the time required for completing work. In contrast, synchronous learning environments require that all learners be online at designated times. Depending on the learning context, this mode can impede participants. A synchronous environment may not be an issue when learners have compatible schedules and are in geographical proximity; however, working professionals with family and other obligations may find it difficult to be online at a prescribed time, and differences in time zones may make synchronous sessions occur at inconvenient times for others. If synchronous scheduling is planned, offering choices to accommodate learners is suggested.

The concepts presented in this book are applicable for many online learning environments; however, we define online learning as taking place in a completely online environment, with no face-to-face interaction. When learning is totally online, designers and instructors must rely more completely on delivery mechanisms and instructional strategies. We believe our examples that address this potentially most challenging mode can easily be applied to the other forms of online learning. In the next section, we examine the growth of online learning in several areas. Understanding how to design meaningful online learning environments is critical as this type of learning becomes commonplace in a wide variety of settings. Knowing how to align instructional strategies, learning activities, and the technologies that support them will lead to meaningful learning outcomes that are needed for learners in diverse situations.

Higher Education

Although enrollments in higher education institutions are decreasing overall, distance education enrollments have grown. Universities that formerly offered only on-campus undergraduate courses are increasingly turning to online courses to meet greater demand from students, offer additional course sections, and solve shortages of classroom space (Poulin & Straut, 2016). The 13th and final annual “Online Report Card” noted that distance education has become mainstream, with more than 25% of higher education students taking an online course (Allen & Seaman, 2016). Online learning has enabled continuing education for adults pursuing graduate degrees as its flexibility allows individuals to fit coursework into their schedules in a way that works best for them. In addition to traditional degree programs, certificate programs that focus on a specialized area or build advanced skills can enhance one’s current credentials or equip one to explore new positions.

Potential students have many choices to consider when exploring options for higher education in online environments. Some institutions are entirely online; others are traditional public or private colleges and universities who have added online course options and/or whole degree programs to their traditional offerings. While non-accredited schools may provide a high-quality educational experience, some organizations are primarily in the business of making money, rather than focusing on student learning.

Online learning for students in higher education typically involves courses with a limited number of participants. In contrast, the massive open online course (MOOC) movement is defined as “A course of study made available over the Internet without charge to a very large number of people: anyone who decides to take a MOOC simply logs on to the website and signs up” (Oxford Dictionaries Online). MOOCs can expand access to highly credentialed instructors and expertly crafted content from top-level universities and enable global learning communities where participants share experiences and resources (Bonk, Lee, Reynolds, & Reeves, 2015).

K–12 Education

Although online learning began primarily in higher education, it has also become widespread in K–12 education. Like higher education, the roots of K–12 online learning lie in distance education that utilized print, CD-ROMS, video conferencing, and other pre-Internet resources (Evergreen, 2015). In the United States, the first online private school opened in 1991, followed in 1994 by the first online public school (Barbour, 2014). In the mid 1990s, the Florida Virtual School and Virtual High School were developed, which continue to be major forces in the field of K–12 online education. Since that time, many states and school districts have begun offering online coursework, with varying degrees of state and federal support. Free, publicly funded charter schools are another type of online learning environment for K–12 students. Over 2.2 million K–12 students are estimated to be taking approximately 3.8 million online courses (Evergreen, 2015). Instructional products and courses may be developed locally or outsourced to suppliers and vendors, who offer courses and related services for schools to license or purchase.

For K–12 students, online learning offers opportunities for taking supplemental courses. High school students may enroll in advanced courses not available in their home school districts or enroll for credit recovery to retake a failed course. Students with exceptional needs may benefit from learning in an online environment where learning may be personalized. Personalized learning begins with a personalized education plan for each student (and is not limited to students with special needs). Adaptive software is then employed to individualize instruction and match learning activities to the student’s current level (Domenech, Sherman, & Brown, 2016). Differentiated instruction in an online environment can also support diverse learners who may be gifted, struggle with traditional classroom environments, have limited English proficiency, or cope with various disabilities (Cavanaugh & Blomeyer, 2007). For other students, online learning can help them to continue their education during illness, frequent moves, participation in athletics or arts, or other conditions that prevent regular school attendance. In all these cases, modules of online learning can be offered as required to allow these learners to move forward relatively independently to meet their needs.

Corporate Education

Online learning has the potential to be flexible, cost-effective, accessible, responsive, adaptable, and to support diversity in learners. These qualities make this type of education very attractive to organizations for training purposes. Corporations are taking advantage of online learning environments to cut professional development costs associated with face-to-face training, where travel, lodging, and meals may be necessary. The challenges of globalization and rapid changes in industry require flexible, quickly formulated strategies that also make online training an attractive option. In the past 20 years, U.S. companies utilizing e-learning have increased from 4% to 77%, with growth expected to continue (Vernau & Hauptmann, 2014). Companies support the need to change quickly by providing education as needed via online training modules that can be easily updated and/or repurposed. Mobile devices facilitate ubiquitous learning and enable microlearning experiences. Microlearning involves just-in-time delivery of small, targeted “nuggets” of specific content. This type of direct performance support can be both effective and efficient. Technologies can support learners in multiple ways, including use of simulations, augmented reality, and gamification. These types of technologies allow for active involvement, individual learner customization, critical thinking, and subsequent transfer of learning and will be addressed further in Chapter 4.

Government Education

Federal, state, and local government agencies are turning to online education to equip workers with a broad range of knowledge and skills. Faced with continuing budget cuts, online training can provide learning that is necessary to meet an agency’s or institution’s educational objectives. For example, ASI Government offers an extensive range of online learning modules covering topics such as federal acquisition, contracting, and certification modules for individuals involved in government contracting and procurement activities and functions. The U.S. military is also looking to online solutions for its forces’ learning needs. The U.S. Army’s Distributed Learning System office developed an e-learning program for basic and advanced IT training, areas of certification, and content for Career Gap Training (Skillsoft, 2015). The military is also moving to mobile learning (mLearning) solutions. mLearning is particularly useful for training in mandatory topics for compliance purposes, with advantages including convenience, low bandwidth requirements, and secure training using protocols for restricted access (Fayad, 2015).

Healthcare Education

Changes in the U.S. healthcare industry have sharpened the focus on provider performance that positively influences patient outcomes. Cervero and Gaines (2014) summarized systematic reviews of continuing medical education’s (CME) effectiveness and found that these reviews substantiated previous research indicating: “CME that is more interactive, uses more methods, involves multiple exposures, is longer, and is focused on outcomes that are considered important by physicians lead to more positive outcomes” (p. 10). Online learning may be particularly effective for this type of CME, with interactive learning modules incorporating a variety of media, technologies, and instructional strategies. Well-designed online CME allows participants to control interactions with learning modules—working at their own pace, revisiting and reviewing previous learning, and engaging in a community of practice. Balmer and McMahon (2015, p. 2) noted that shifting to online education can result in “simulated and actual performance improvement and behavioral change” rather than simple knowledge acquisition.

A study commissioned by the World Health Organization found that e-learning for undergraduates preparing for a healthcare career can be beneficial in meeting shortages of adequately trained workers in this field. Online learning can address a lack of educators to train these students in face-to-face classrooms. Further, online environments that use immersive learning experiences such as 3D, augmented reality may be particularly well suited for health learning outcomes that often include a spatial or visualization component. Further the ubiquitous learnin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

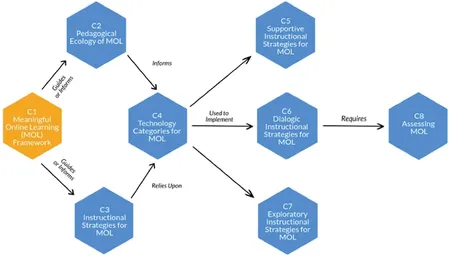

- 1 Meaningful Online Learning: Theories, Concepts, and Strategies

- 2 Pedagogical Ecology of Meaningful Online Learning: Meaningful Online Learning Design Framework

- 3 Instructional Strategies for Meaningful Online Learning

- 4 Technologies to Support Meaningful Online Learning

- 5 Supportive Instructional Strategies for Meaningful Online Learning

- 6 Dialogic Instructional Strategies for Meaningful Online Learning

- 7 Exploratory Instructional Strategies for Meaningful Online Learning

- 8 Assessing Meaningful Online Learning

- Index