A History of the Muslim World since 1260

The Making of a Global Community

- 578 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

A History of the Muslim World since 1260

The Making of a Global Community

About this book

A History of the Muslim World since 1260 continues the narrative begun by A History of the Muslim World to 1750 by tracing the development of Muslim societies, institutions, and doctrines from the time of the Mongol conquests through to the present day. It offers students a balanced coverage of Muslim societies that extend from Western Europe to Southeast Asia. Whereas it presents a multifaceted examination of Muslim cultures, it focuses on analysing the interaction between the expression of faith and contemporary social conditions.

This extensively updated second edition is now in full colour, and the chronology of the book has been extended to include recent developments in the Muslim world. The images and maps have also been refreshed, and the literature has been updated to include the latest research from the last 10 years, including sections dedicated to the roles and status of women within Muslim societies throughout history.

Divided chronologically into three parts and accompanied by a detailed glossary, A History of the Muslim World since 1260 is a perfect introduction for all students of the history of Muslim societies.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

PART ONE

Mongol Hegemony, 1260–1405

| CHRONOLOGY | |

| 1210–1236 | Reign of Iltutmish, founder of Delhi Sultanate |

| 1219–1222 | Campaigns of Chinggis into Muslim world |

| 1240s | Batu founds Saray, begins to administer the Golden Horde |

| 1250 | Mamluks seize power in Egypt and Syria |

| 1253–1260 | Hulagu’s campaign |

| ca. 1250–ca. 1290 | Career of Hajji Bektash |

| 1260 | Mamluks defeat Hulagu’s army at ‘Ayn Jalut |

| 1260–1265 | Hulagu is first ruler of Il-khanate, establishes Maragha observatory |

| 1261 | Byzantines regain Constantinople from Latin Kingdom |

| 1269 | Marinids replace Almohads in Morocco |

| 1271–1295 | Marco Polo’s adventures in the Mongol Empire |

| ca. 1280–1326 | Career of Osman, founder of Ottoman dynasty |

| ca. 1280–1334 | Career of Shaykh Safi al-Din |

| 1291 | Mamluks capture the last crusader castle in Syria |

| ca. 1290–1327 | Career of Ibn Taymiya in Mamluk Empire |

| 1310–1341 | Third, and most successful, reign of Mamluk ruler, al-Nasir Muhammad |

| 1313–1341 | Reign of Uzbeg and the Islamization of the Golden Horde |

| 1325–1351 | Reign of Muhammad ibn Tughluq of Delhi |

| 1325–1349 | Ibn Battuta’s journey east; serves Ibn Tughluq seven years |

| 1326–1362 | Reign of Orhan of Ottoman Sultanate |

| 1334 | Schism in Chaghatay Khanate, Transoxiana is lost |

| 1335 | Collapse of Il-khanate |

| ca. 1335–1375 | Career of Ibn al-Shatir |

| 1347 | First wave of plague |

| ca. 1350–1390 | Career of Hafez |

| ca. 1350–1398 | Career of Baha al-Din Naqshband |

| ca. 1350 | Consensus has been achieved in most madhhabs that, theoretically, ijtihad is no longer permitted |

| 1359–1377 | Civil war in Golden Horde; Toqtamish secures control |

| ca. 1360–1406 | Career of Ibn Khaldun |

| 1368 | Ming dynasty overthrows Yuan dynasty of the Mongols in China |

| 1370 | Timur’s career begins in Transoxiana |

| 1381–1402 | Timur’s campaigns from Ankara to New Saray to Delhi |

| 1405 | Death of Timur |

CHAPTER 1

The Great Transformation

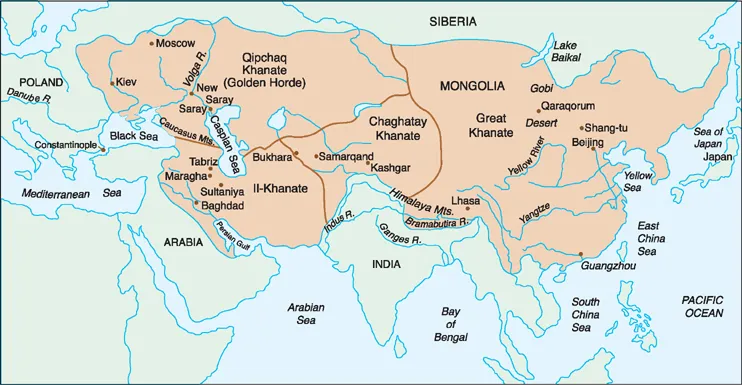

The Mongol Khanates

The Golden Horde

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Maps

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Note on Transliteration, Dating, and “the Muslim World”

- Introduction The Making of a Civilization, 610–1260

- Part One Mongol Hegemony, 1260–1405

- Part Two Muslim Ascendancy, 1405–1750

- Part Three The World Turned Upside Down, 1750–Present

- Glossary

- Index