![]()

Chapter 1

Native North America Before European Contact

Artist’s rendition of Cahokia

Stories Versus Science

Beginnings

We Were Always Here

The Scientific Evidence

Clovis and Folsom Cultures

Changes in the West

California Indians

The Northwest

The Great Basin and the Plains

Agriculture-Based Societies in the Southwest

Cultural Diversity and the Arrival of Maize

The “Chaco Phenomenon”

Hohokam and Mesa Verde Cultures

Eastern Woodlands

Early Eastern Woodlands Traditions

Adena and Hopewell Cultures

Mississippian Chiefdoms

The Iroquois

Stories Versus Science

Pawnees explain their beginnings this way: the first Pawnee man and woman received life from Tirawa, a male spirit of the upper cosmos who held the powers of thunder and lightning. The Pawnee male was represented by the Morning Star of the East, woman by the Evening Star in the West. Long ago, they and their descendants migrated from colder climates, south into the plains of North America. Pawnee origin stories vividly tell of a universe divided into male and female components. The Pawnee farmed and hunted along the Platte, Republican, and Loup rivers that interlocked parts of Nebraska, Wyoming, and Colorado, along the outer reaches of the northern plains. Their settlement patterns and gendered division of labor complemented the Pawnee bond with the stars and earth. This relationship was evident in a rich Pawnee ceremonial, wherein Pawnees set corn medicine bundles next to posts at the center of villages and used the stars and an understanding of four sacred cardinal directions to target fertile lands. Broken into four village divisions aligned with the four cardinal points, each village had corn and medicine bundles of different types to sustain balance between Tirawa and Mother Earth, the female cosmic being of fertility. Mother Maize was the most powerful of the corns. Pawnee gave thanks to Mother Maize through elaborate rituals that included gifts of bison meat. The cosmic balance between the Morning Star and the Evening Star—the original man and woman—was maintained in all facets of Pawnee life.

Origin stories, like the one above, explain how a people came to be. Each Native American tribal group has an origin story, which is the root of the group’s cultural traditions. The numerous and diverse origin stories of Native Americans sharply counter the single origin concept posited by each of the major western religions, and, in so doing, set the stage for conflict once native peoples meet Europeans, a clash of cultures that inevitably shaped the history of the Western Hemisphere. But native origin stories also counter science, as do all religious and spiritual creation stories. The stories reference upper worlds and under worlds, concepts at odds with science. They do not follow linear time as scientists do, and they are often vague about tribal peoples’ patterns of settlement and places of origin. Today, the issue is not that tribal origin stories and western religion creationism are incompatible with one another but rather that traditional native origin stories are incompatible with the archaeological record.

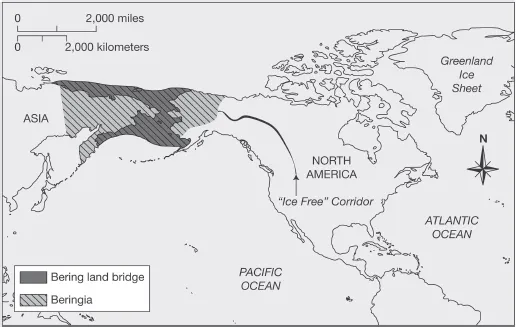

Scientists postulate that an ice-free corridor, the Bering land bridge, opened in successive periods roughly between 30,000 and 13,000 years ago, connecting Alaska and Siberia and allowing for human migration from East Asia into North America. Scientists’ efforts to determine the exact timing and scale of each wave of migration are ongoing. Native Americans, however, believe the Bering land bridge argument has less to do with science and more to do with justifying native land dispossession. If native peoples did not originate in North America, but only migrated there, then they were just one of many waves of colonizers of the Western Hemisphere, making their ownership of the land temporary and subject to shifting sources of power. Moreover, many Native Americans see scientific arguments as unnecessary because they believe their stories tell them everything they need to know about their own beginnings.

Chronology

| 30,000 BCE–13,000 BCE | Bering land bridge open |

| 13,500 BCE–12,900 BCE | Clovis culture |

| 11,000 BCE–6,000 BCE | Folsom culture, expansion of Paleo-Indian hunters on the Plains, and the emergence of agriculture |

| 900 CE–1150 CE | “Chaco Phenomenon” |

| 300 CE–1450 CE | Hohokam tradition |

| 500 CE–1300 CE | Mesa Verde |

| 2200 BCE–700 CE | Poverty Point mound builders |

| 1500 BCE | Reliance on cultigens in the Eastern Woodlands |

| 1000 BCE–200 CE | Adena complex |

| 200 BCE–500 CE | Hopewell culture |

| 700 CE–1200 CE | Mississippian culture and Cahokia |

| 1200 CE–1450 CE | Expansion of Moundville and beginning of Mississippian decline |

| circa 700 CE–European Contact | Natchez, Coosa, and other remnant Mississippian chiefdoms in the Deep South |

| 1000 BCE–European Contact | Growth and concentration of Iroquois cultures |

Key Questions

- How and when did people migrate to North America?

- How did Indian life change in the West after the Clovis and Folsom cultures died out?

- Describe and analyze the different phases of social and cultural development in the Southwest.

- What kinds of societies and cultures developed in the Eastern Woodlands?

Beginnings

Many Native Americans insist that their people populated North America long before the dates postulated by the Bering land bridge theory. They may be right. Many Pacific coast peoples have oral traditions of great floods that carried them to the lands on which they resided. In the Bella Coola story, “When the water rose to the top of the mountain,” they tied up their boats, placed their ceremonial masks on the land, and planted their villages. “The masks are still there and turned to stone,” referencing the rock cliffs along the coast. The Bella Coola, like their neighbors, may have experienced flooding when the glaciers receded at the end of last Ice Age, during a period known as the Wisconsin Glaciation, when the land bridge opened between 30,000 BCE to 11,000 BCE (before the common era). If coastal peoples witnessed the rising tides of glacial warming, then they could have been in North America long before the supposed Bering corridor ever opened (see Map 1.1).

We Were Always Here

Prominent Native American scholar and activist Vine Deloria Jr. argues that native stories are “geomythology.” If geologists who study the earth can use sophisticated core samples of soil to date sediment activity and the expansion of topographical features over time, such geological data should not disqualify native stories as having similar, if not more important, value as a dating technique. In fact, native stories might be as far as people need to look. There are stories that tell of receding glaciers pouring water over the landscape. Hopis and other peoples in the Southwest talk of vast fires, perhaps because of volcanic eruptions dating back hundreds of thousands of years. A few Indian stories contain precise descriptions of existing mountains and craters, possibly a topography that predates the familiar. And Pacific Northwest peoples speak of houses that were once on stilts to ward off mammoths. Students and scholars cannot dismiss all these stories as fiction. Traditionalists among Native Americans put it quite simply: “We have always been here.” If Native Americans were here before the theoretical opening of the Bering land bridge, then the scientific argument that people crossed an open bridge either collapses entirely, needs much more investigation, or must include native origin stories.

Map 1.1 Bering land bridge

The Scientific Evidence

Scientists do not know the precise details of the first population movements to the Western Hemisphere. Many paleoanthropologists (scientists who study the origins of human beings) believe that people from northeastern Asia crossed the Bering Strait using a land bridge that connected Asia to what is now Alaska. Samples of soil drilled from the seabed between Alaska and present-day Siberia confirm that the Bering land bridge once existed. There is general agreement that hunter-gatherers crossed the bridge by migrating through a narrow ice-free corridor. Still, questions linger. When, how, and in what numbers did these people, known as Paleo-Indians, migrate?

One recent discovery narrows the time frame. In 2013, excavations of an 11,500-year-old encampment in the Tanana River Valley of Central Alaska unearthed from a burial pit the skeletal remains of what appears to be a six-week-old girl. Named “Sunrise Girl-Child” by the team of scientists, the youngster belonged to a subgroup of migrating people who opted not to continue their journey and instead established a small community that eventually failed. A complete DNA analysis was finally completed in January 2018, and scientists at the University of Alaska and the University of Copenhagen found that about half of the child’s DNA is that of Northern Eurasians, or Siberians, while the remainder is consistent with the DNA of Native Americans. This finding fits well into recent scholarship regarding the Bering Strait Theory of native origins. Most of the Canadian-Alaskan-Siberian stretch was covered completely in ice until about 12,500 years ago, note scientists at the University of Copenhagen, and therefore “incapable of sustaining human life” at any earlier time. “The land was completely naked and barren” and could not provide for migrating herds of bison for hundreds of years. The combined discoveries of ice sheets across the region and the finding of Sunrise Child-Girl certainly places humans along the path of the Bering Strait migrations and restricts their travel to an age more recent than the theory initially offered.

There are additional wrinkles to the long-accepted Bering Strait argument. What explains the presence of 12,000-year-old human remains found in an underwater Mexican cave in the early twenty-first century? The bones of a teenage girl were discovered in a 100-foot-deep water-filled pit called Hoyo Negro, or Black Hole. Her mitochondrial DNA indicated an Asian lineage, a trait exhibited by about 10 percent of the Native American population. The Bering Strait land bridge timeline now generally accepted does not mesh with the discovery of this teenage girl’s bones. Meadowcroft Rockshelter, near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, gives archaeologists a glimpse into the lives of the earliest people of the Eastern Woodlands, a commonly used designation for the territories east of the Mississippi River, running from present-day Canada to the Gulf Coast. Skeptics have claimed that t...