The Question

What Does this Introduction to Global Politics Do?

This is a textbook, but it is more than that. It is a guide for students to the questions about global politics that puzzle all of us. There are no easy answers to be had, and none of the chapters pretend that there are. There are only difficult and challenging questions – that lead to more difficult and more challenging questions. We think this is because the difficulties of global politics reflect the difficulties of ‘life, the universe, and everything’. This makes this book in some sense a sort of hitch-hiker’s guide. We don’t give you answers, not even Douglas Adams’ (1979) answer – you will need to read his Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (if you haven’t already) if you want to know his answer – but we do try to give you a guide to how other people have formulated questions and how they have attempted to respond to them. Many textbooks behave as if the ‘great minds’ have come up with the answers: they haven’t. The questions remain open and intractable, there for each new generation to formulate and tackle for themselves. This section of the introduction explores what questions we address, and discusses how the approach this book takes relates to that taken by other textbooks of global politics or international relations.

Figure 1.1 Martin Freeman as Arthur Dent and Mos Def as Ford Prefect in Touchstone Pictures’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Ronald Grant Archive

So, instead of starting from the sorts of explanations of global politics that ‘great minds’ have given (as those textbooks do that start from ‘theories’) or starting from some problem in global politics (as those textbooks do that start from ‘issues’), in this book we start with questions. As we have been teaching global politics, our students have asked us very intriguing questions. Often we have found that our students’ curiosity is motivated by the same sorts of questions that stimulate our own interest in global politics. In this book we have tried to put together a set of these questions. Each chapter starts by introducing its main question. So this book tackles twenty-five main questions. But often when we start thinking about one particular question we realise that it raises a number of other questions. Each chapter therefore focuses on one main question – the one you see in the chapter heading – but it will also discuss related questions and make reference to other chapters and their questions. We sometimes use a feature called ‘marginal comments’ to alert you to how the discussion in one chapter links to the question or explanation in another.

The way we plan to use comments in the margins of the textbook is explained here.

Let us briefly explain what we mean by questions being related in this way.

You might, for example, wonder why people can’t freely decide where they want to live (Chapter 10). Some of you may indeed have encountered this problem when you applied to a university: you may have wished to go to a university that is not in the country of which you are a citizen and this might have set off a series of problems. You may have had to apply for a visa and pay higher tuition fees, and you may at the same time be ineligible for (some of the) available scholarships and find it difficult to acquire the right paperwork to be able to get a part-time job. Your citizenship has a material impact on how you can live your life.

Figure 1.2 ‘Have you ever tried pushing a piece of string?’ Cartoonist: Flanagan, Mike. Cartoonstock ID: mfln6314

So, in some way, you know the answer to the question: people can’t move freely because states can decide who may and may not legally live within their borders. But how is it that states have this right? And why is the world divided into states in the first place (Chapter 11)? As you think about this you may notice that we often talk of this division in terms of ‘nation-states’. But how and why have nations and states come to be related in this way? Does our allegiance to a particular nation overlap with our relation to a state (Chapters 12 and 13)? You have now started thinking about how we think about our identity. So now you need to figure out who we think we are (Chapter 5) and how we even begin to think about the world. For example, in determining how we behave towards others (say, whether we should give them financial assistance), does it matter how we think about their relationship to us (Chapter 2)? Or whether we think they are risky or dangerous (Chapter 23)? If how we think about the world has an impact, then what about particular ways of conceptualising the world and our place within it, such as religious beliefs? How do they affect politics (Chapter 6)? And how do we come to believe what we believe in the first place? In order to understand that, perhaps we need to know how we find out what’s going on in the world (Chapter 8). And, come to think of it, did we start in the best place to think about global politics? We started with you: as good a place as any, you may think. But is there not more to the globe than the people that live on it? As we increasingly worry about climate change, we might wonder whether there is not more to existence than human concerns (Chapter 3).

So, you see, many of our questions are connected with each other. We invariably start with a particular question or concern, and often we may not even realise that it is related to global politics. But as we pursue ways of thinking about and responding to the question we find that new questions are raised, often questions that concern global issues.

Illustrative Example

How Do We Use Illustrative Examples?

What you will find in this book are a lot of fascinating, and at times moving, accounts of what is going on or has gone on in particular places at specific historical points in global history. Sometimes these stories will be large-scale histories and at other times they will recount the experiences of maybe one person and their life. You will get to know a lot about many different places: this section of the introduction will map some of them for you.

The book contains many illustrative examples. We tell you here what we mean by that, and why we think they are important.

Figure 1.3 A Syrian boy in the rebel-held town of Douma in Syria’s eastern Ghouta region, 2017. Photograph: Hamza Al-Ajweh/AFP/Getty Images

When we just explained why questions are often related to each other, we did not have space to say very much about why we are asking the question or who might be affected by it. We briefly showed you how you yourself might have been affected by citizenship regulations, but we did not go into any detail. In each of the chapters, however, the authors tell you at some length about a particular context in which the question they examine has arisen. We call this an illustrative example. It’s an example because for each question there will be many other cases that one could look at in relation to the question and, of course, another case may highlight different issues. But the example chosen will illustrate what issues arise when we explore the question in a particular context. It will show you why the question is important, who is affected by it and what is at stake in responding to it one way or another. You will, of course, have realised that in order to cross a border legally you need the right documentation. And you probably know that many people in different regions of the world attempt to enter countries without the appropriate papers and often they risk their lives in the process. But by looking at the particular example of the US–Mexico border, the author of Chapter 10, Roxanne Doty, is able to show how the US border enforcement policies of the 1990s led to a sharp increase in deaths along the border and how these

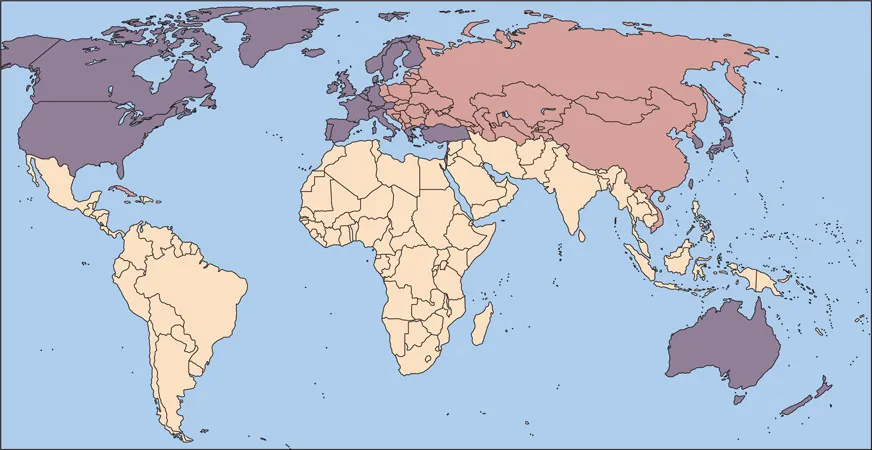

Box 1.1 The Third World

The term ‘third world’ was first coined in 1952. At that time, during the Cold War, the world seemed to be made up of three groups of countries: the ‘modern’, liberal, industrialised countries of the ‘West’ (US, UK, and other European states, Japan, Australia, Canada, and so on), the communist states of the USSR or Soviet Union, and the ‘underdeveloped’ or non-industrialised states: states in Africa, Asia, South America. These groups were seen as making up the first, second, and third ‘worlds’, respectively. The term ‘third world’ was problematic, not only because this picture of the world was oversimplified from the start and became increasingly so as countries in Asia for example began to industrialise rapidly, and later when the communist regimes of the Soviet Union collapsed, but also because of the implicit hierarchy of ‘first’, ‘second’, and ‘third’. Alternative terminologies have been suggested: ‘developing world’, ‘emerging countries’, or the division North–South, for example, but none of these are satisfactory either and the term ‘third world’ remains in use.

Figure 1.4 The three ‘worlds’. Public domain

policies were linked to larger developments in economics and security. And in Chapter 2, Véronique Pin-Fat examines the dangers refugees from Syria face in some detail.

For many people the question of which country they are authorised to live in is one of life and death. We think it is important to acknowledge this when we ask why people cannot simply choose where they wish to live. This is also the case with the other questions explored in the book. When we ask how we can move beyond conflict, we need to understand why a conflict had arisen in the first place (Chapter 24). The precise circumstances matter. And when we do decide that we want to do something, say to work for the overthrow of a regime we find oppressive, as people in Egypt did in 2011, or to get people not to waste resources, we need to think about how exactly we intend to go about it. Do we march and demonstrate or do we work through non-governmental organisations (NGOs) (Chapter 4)? How do we actually organise our activism (Chapter 9)? What you will come across in the chapters of this book is a series of detailed accounts, sometimes heart-rending, of things that have happened or are happening in particular places at particular times. This means that as you read the book, you will learn quite a bit about different places across the globe, the places where ‘global politics’ happen. We’ll try to map some of these places in this section of the introduction.

What counts as a ‘global’ issue is not obvious, and people will have different views on this. And the terms people use are different too: some people talk of ‘global politics’, as this book does, and others of ‘world politics’. The traditional term is ‘international politics’ or ‘international relations’ but we don’t use either of these traditional terms here, since they seem to limit global politics to relations between states or nations.

Some chapters explore phenomena that are obviously global in scope, such as climate change (Chapter 3), but they might still affect people in different places differently. This is important in order to understand the politics: those people who are in danger of losing their livelihoods and homes because of the impact of hurricanes, for example, are likely to think that climate change is a very pressing issue, whereas people living in areas not so affected might not want to assign resources to avoiding environmental change. Similarly, while there is inequality across the globe and within each country, what this means, and what it means to be poor, depends on where you live. Chapter 19 examines developed countries in Europe, North America and Japan, but also developing and emerging countries such as Brazil, Russia, India and China.

You will also learn about many other places and how they relate to each other, creating what we call global politics and responding to it. Asia, for example, is prominent in this book. Chapter 12 looks at Chinese identity and how the Chinese state regards so-called Overseas Chinese. Chapter 16 examines how colonialism worked in India. We have already noted that Chapter 19 gives you information about inequality in Japan, India and China. Chapter 20 examines responses to poverty in South Asia, Bangladesh in particular. Chapter 21 discusses the situation of women in Afghanistan. Chapter 24 takes you to a different part of Asia, North Korea and South Korea, and looks at the difficult relations between these two countries and how they relate to wider issues in global politics, especially the Cold War. We often need to understand what happened earlier to better understand global politics today. The question of colonialism in India cannot be understood without a discussion of how Britain benefit...