![]()

1 Second Language Learning

Key Concepts and Issues

1.1 Introduction

This preparatory chapter provides an overview of key concepts and issues which will recur throughout the book. We offer introductory definitions of a range of terms, and try to equip the reader with the means to compare the goals and claims of particular theories with one another. We also summarize key issues, and indicate where they will be explored in more detail later in the book.

The main themes to be dealt with in following sections are:

- 1.2 What makes for a “good” explanation or theory

- 1.3 Views on the nature of language

- 1.4 Views of the language learning process

- 1.5 Views of the language learner

- 1.6 Links between language learning theory and social practice.

First, however, we must offer a preliminary definition of our most central concept, “second language learning” (SLL). We define this broadly, to include the learning of any language, to any level, provided only that the learning of the “second” language takes place sometime later than the learning by infants and very young children of their first language(s) (i.e. from around the age of 4).

Simultaneous infant bilingualism from birth is of course a common phenomenon, but this is a specialist topic, with its own literature, which we do not try to address in this book; for overviews see, for example, Serratrice (2013) and Nicoladis (2018). We do, however, take account of the thriving research interest in interactions and mutual influences between “first” languages (L1s) and later-acquired languages, surveyed, for example, in Cook and Li Wei (2016) and Pavlenko (2011); aspects of this work are discussed in later chapters.

For us, therefore, “second languages” are any languages learned later than in earliest childhood. They may indeed be the second language (the L2) the learner is working with, in a literal sense, or they may be his/her third, fourth or fifth language. They encompass both languages of wider communication encountered within the local region or community (e.g. in educational institutions, at the workplace or in the media) and truly foreign languages, which have no substantial local uses or numbers of speakers. We include “foreign” languages under our more general term of “second” languages because we believe that many (if not all) of the underlying learning processes are broadly similar for more local and more remote target languages, despite differing learning purposes, circumstances and, often, the quantity and nature of experiences with the language. (And, of course, languages are increasingly accessible via the internet, a means of communication which cuts across any simple “local”/“foreign” distinction.)

We are also interested in all kinds of learning, whether formal, planned and systematic (as in classroom-based learning) or informal and incidental to communication (as when a new language is “picked up” in the community or via the internet). Following the proposals of Stephen Krashen (1981), some L2 researchers have made a principled terminological distinction between formal, conscious learning and informal, unconscious acquisition. Krashen’s “Acquisition-Learning” hypothesis is discussed further in Chapter 2; however, many researchers in the field do not distinguish between the two terms, and unless specially indicated, we ourselves will be using both terms interchangeably. (Note, in Chapters 4 and 5, where the distinction between conscious and unconscious learning is central, we will use the terms “implicit” and “explicit” learning, which often broadly align with the distinction between “acquisition” and “learning”.)

1.2 What Makes for a Good Theory?

Second language (L2) learning is an immensely complex phenomenon. Millions of human beings experience L2 learning and may have a good practical understanding of activities that helped them to learn. But this experience and common-sense understanding are clearly not enough to help us explain the learning process fully. We know, for a start, that people cannot reliably describe the language system that they have internalized, nor the mechanisms that process, store and retrieve many aspects of that new language. We need to understand L2 learning better than we do, for two basic reasons:

- Because improved knowledge in this domain is interesting in itself and can contribute to a more general understanding about the nature of language, human learning and intercultural communication, and thus about the human mind itself, as well as how all these affect each other;

- Because the knowledge will be useful. If we become better able to account for both success and failure in L2 learning, there will be a payoff for many teachers and their learners.

We can only pursue a better understanding of L2 learning in an organized and productive way if our efforts are guided by some form of theory (Hulstijn, 2014; Jordan, 2013; VanPatten & J. Williams, 2015). For our purposes, a theory is a (more or less) abstract set of claims about significant entities within the phenomenon under study, the relationships between them, and the processes that bring about change. Thus, a theory aims not just at description, but at explanation. Theories may be embryonic and restricted in scope, or more elaborate, explicit and comprehensive. They may deal with different areas of interest; thus, a property theory will be primarily concerned with modelling the nature of the language system to be acquired, while a transition theory will be primarily concerned with modelling the developmental processes of acquisition (Gregg, 2003; Jordan, 2004, Chapter 5; Sharwood Smith, Truscott, & Hawkins, 2013). One particular property theory may deal only with one domain of language (such as morphosyntax, phonology or the lexicon). Likewise, one particular transition theory itself may deal only with a particular stage of L2 learning or with the learning of some particular subcomponent of language; or it may propose learning mechanisms that are much more general in scope. Worthwhile theories are collaboratively produced and evolve through a process of systematic enquiry in which the claims of the theory are assessed against some kind of evidence or data. This may take place through hypothesis-testing through formal experiment, or through more ecological procedures, where naturally occurring data are analysed. In addition, bottom-up theory development can happen, usually through reflections on data (whether naturally or experimentally elicited), from which theories can emerge and become articulated. (There is now a considerable number of manuals offering guidance on research methods in both traditions, such as Mackey & Gass, 2012; Phakiti, De Costa, Plonsky, & Starfield, 2018. We will provide basic introductions to a range of research procedures as needed, throughout the book and also in the Glossary.) Finally, the process of theory building is a reflexive one; new developments in the theory lead to the need to collect new information and explore different phenomena and different patterns in the potentially infinite world of “facts” and data. Puzzling “facts” and patterns that fail to fit with expectations in turn lead to new, more powerful theoretical insights.

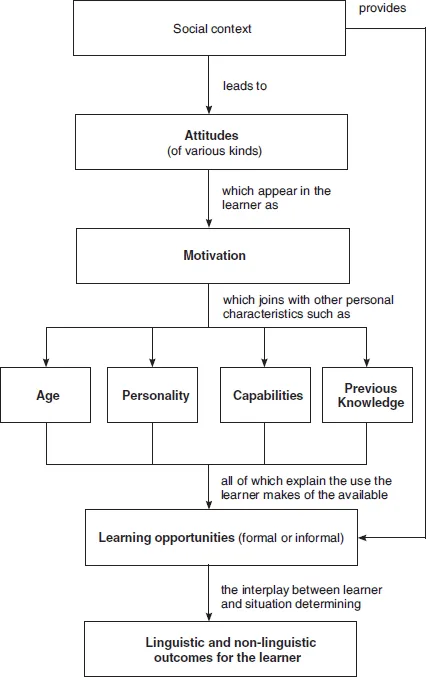

To make these ideas more concrete, an early “model” of L2 learning is shown in Figure 1.1, taken from Spolsky (1989). This model represents a “general theory of second language learning”, as the proposer described it (p. 14). The model encapsulates this researcher’s theoretical views on the overall relationship between contextual factors, individual learner differences, learning opportunities and learning outcomes. It is thus an ambitious model, in the breadth of phenomena it is trying to explain. The rectangular boxes show the factors (or variables) which the researcher believes are most significant for learning, that is, where variation can lead to differences in success or failure. The arrows connecting the various boxes show directions of influence. The contents of the various boxes are defined at great length, as consisting of clusters of interacting “Conditions” (74 in all: 1989, pp. 16–25), which make language learning success more or less likely. These summarize the results of a great variety of empirical language learning research, as Spolsky interprets them.

Figure 1.1Spolsky’s General Model of Second Language Learning

How would we begin to evaluate this or any other model, or, even more modestly, to decide that this was a view of the language learning process we could work with? This would depend partly on the extent to which the author has taken account of evidence and provided a systematic account of it. It would also depend on rather broader philosophical positions: for example, are we satisfied with an account of human learning which sees individual differences as both relatively fixed and also highly influential for learning? Finally, it would also depend on the particular focus of our own interests, within L2 learning; this particular model seems well adapted for the study of the individual learner, for example, but has relatively little to say about the social relationships in which they engage, the way they process new language, nor the kinds of language system they construct.

Since at least the mid 1990s, there has been debate about the adequacy of the theoretical frameworks used to underpin research on L2 learning. One main line of criticism has been that L2 research (as exemplified by Spolsky, 1989) has historically been too preoccupied with the cognition of the individual learner, and sociocultural dimensions of learning have been neglected. From this perspective language is an essentially social phenomenon, and L2 learning itself is a “social accomplishment”, which is “situated in social interaction” (Firth & Wagner, 2007, p. 807) and discoverable through scrutiny of L2 use, using techniques such as conversation analysis (Pekarek Doehler, 2010; Kasper & Wagner, 2011). A second—though not unrelated—debate has concerned the extent to which L2 theorizing has become too broad. Long (1993) and others argued that “normal science” advanced through competition between a limited number of theories, and that the L2 field was weakened by theory proliferation. This received a vigorous riposte from Lantolf (1996) among others, advancing the postmodern view that knowledge claims are a matter of discourses. From this point of view, all scientific theories are viewed as “metaphors that have achieved the status of acceptance by a group of people we refer to as scientists” (p. 721), and scientific theory building is all about “taking metaphors seriously” (p. 723). For Lantolf, any reduction in the number of “official metaphors” debated could “suffocate” those espousing different world views.

These debates about the nature of knowledge, theory and explanation have persisted up to the present. It is probably fair to say that the majority of L2 researchers today adopt some version of a “rationalist” or “realist” position ( Jordan, 2004; Long, 2007; Sealey & Carter, 2004, 2014). This position is grounded in the philosophical view that an objective and knowable world exists (i.e. not only discourses), and that it is possible to build and test successively more powerful explanations of how that world works, through systematic programmes of enquiry and of problem-solving. Indeed, this is the position we take in this book. However, like numerous others ( Jordan, 2004; Ortega, 2011; Rothman & VanPatten, 2013; Zuengler & Miller, 2006), we acknowledge that a proliferation of theories is necessary to make better sense of the varied phenomena of SLL, the agency of language learners, and the contexts and communities of practice in which they operate. We believe that our understanding advances best where theories are freely debated and challenged. As later chapters show, we accommodate a range of linguistic, cognitive, sociocultural and poststructuralist perspectives. But in all cases, we would expect to find the following:

- Clear and explicit statements about the ground the theory aims to cover and the claims it is making;

- Systematic procedures for confirming/disconfirming the theory, through data gathering and interpretation: the claims of a good theory must be testable/falsifiable in some way;

- Not only descriptions of L2 phenomena, but attempts to explain why they are so, and to propose mechanisms for change, i.e. some form of transition theory;

- Last but not least, engagement with other theories in the field, and serious attempts to account for at least some of the phenomena which are “common ground” in ongoing public discussion (VanPatten & J. Williams, 2015). Remaining sections of this chapter offer a preliminary overview of numbers of these.

(For fuller discussion of rationalist evaluation criteria, see Gregg, 2003; Hulstijn, 2014; Jordan, 2004, pp. 87–122; Sealey & Carter, 2004, pp. 85–106; and for a poststructuralist perspective on theory in second language acquisition and applied linguistics, see McNamara, 2012; S. Talmy, 2014.)

1.3 Views on the Nature of Language

1.3.1 Levels of Language

Linguists have traditionally viewed language as a complex communication system, which must be analysed on a number of levels (or subcomponents), such as phonology, morphology, lexis, syntax, semantics, pragmatics, discourse. (Readers unsure about this basic descriptive terminology will find help from the Glossary, and in more depth from an introductory linguistics text, such as Fromkin, Rodman, & Hyams, 2017.) They have differed about the extent of interconnections between these levels; for example, while, e.g., Chomsky argued at one time that “grammar is autonomous and independent of meaning” (1957, p. 17), another tradition initiated by the British linguist Firth claims that “there is no boundary between lexis and grammar: lexis and grammar are interdependent” (Stubbs, 1996, p. 36). (See also our discussion of O’Grady’s work in Chapter 4.)

In examining different perspectives on SLL, we will first of all be looking at the levels of language which they attempt to take into account. (Does language learning start with words or with pragmatics?) We will also examine the degree of integration or separation that the theories assume, across various...