- 480 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Introduction to Development Economics

About this book

Charged with analyzing and criticizing the way economies develop and grow, development economists play a vital role in attempting to reduce inequality across the world. The fourth edition of this classic textbook introduces students to this vital field. All of the popular aspects of earlier editions are retained with new additions such as the intro

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Introduction

1.1 Introduction

The problems of the economic development of the poor countries of today's world is one of the most widely discussed topics of our time. Experts in various fields such as economics, politics, sociology and engineering have held different views about the nature of underdevelopment and poverty, its causes and its remedies. It has now been fully recognized that the nature and causes of the ‘poverty of the nations’ are very complex and the remedies are neither easy nor quick. The understanding of the problem of underdevelopment requires a good knowledge of certain basic characteristics of the less developed countries (henceforward to be referred to as LDCs). The analysis of these characteristics will shed some light on the peculiar economic and social conditions of production, consumption and distribution of income and wealth in the LDCs, which will help us to draw some policy implications.

1.2 Characteristics of the less developed countries

1.2.1 Low per capita real income

Low per capita real income is generally regarded as one of the main indicators of the socioeconomic conditions of the LDCs. A comparison with the economically developed countries (DCs) is striking (see Tables 1.1–5). It shows very clearly the difference between the DCs and the LDCs. If the per capita income of the United States and India are considered, it is clear that an average Indian earned about 1.5 per cent of the income of an average American in 1999. Most of the LDCs exhibit this very low ratio of income to population. It shows the relatively low level of national income in most LDCs, or a high level of population, or both. Low per capita real income is a reflection of low productivity, low saving and investment and backward technology and resources, while the level of population is determined by complex socioeconomic factors. Hence, the importance of population in relation to national income in the LDCs can hardly be overemphasized, and this is discussed in the next section.

1.2.2 Population

Most LDCs generally experience a high population growth rate or, where the population growth rate is not very high in comparison with other LDCs, the size of the population may be very high (e.g. China and India). LDCs usually experience high birth rates but the advancement of medical science has led to a significant reduction in the death rates (except in some African countries). This has engendered a situation which has been generally termed ‘population explosion’. One of the main implications of such population explosion has been the growth of the proportion of people who live on the subsistence level or ‘poverty line’, defined as the line of minimum calorie intake to stay alive in LDCs. Another aspect of population growth has been the growth of the proportion of unemployed people in the LDCs who tend to migrate, chiefly from the villages to the cities, in search of a livelihood.

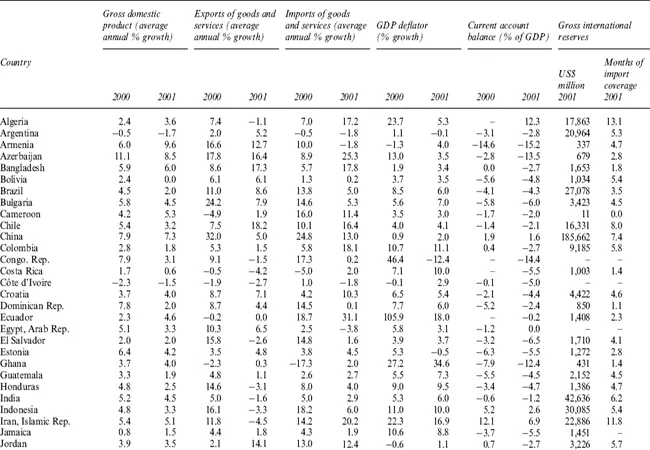

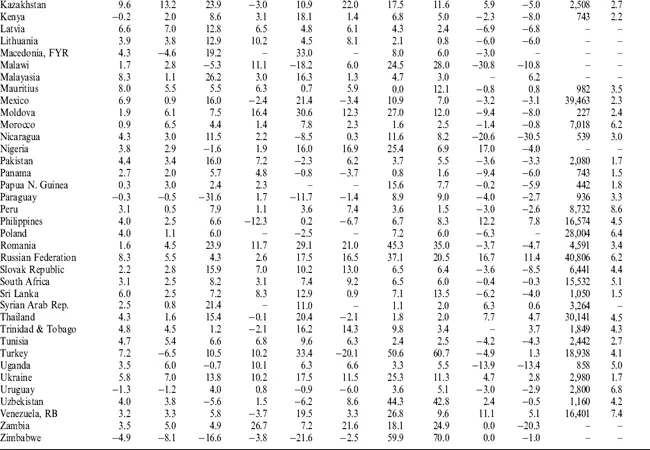

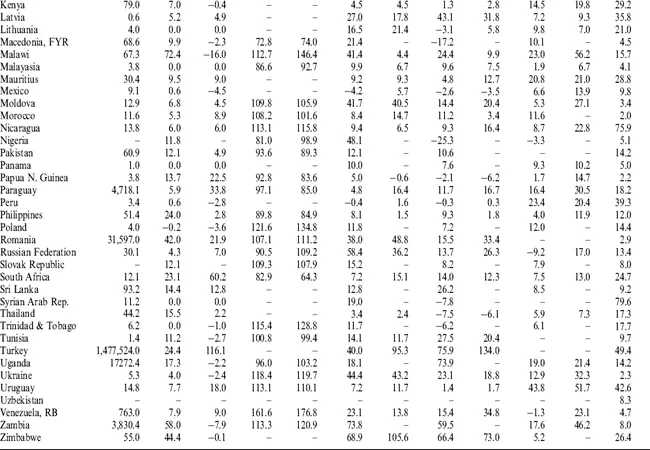

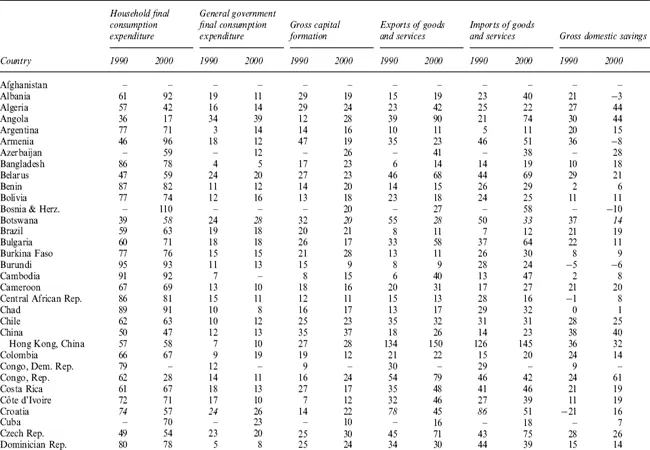

Table 1.1 LDCs' economic performance, 2000–1

Note: Data for 2001 are the latest preliminary estimates, and may differ from those in earlier World Bank publications.

Source: World Bank staff estimates.

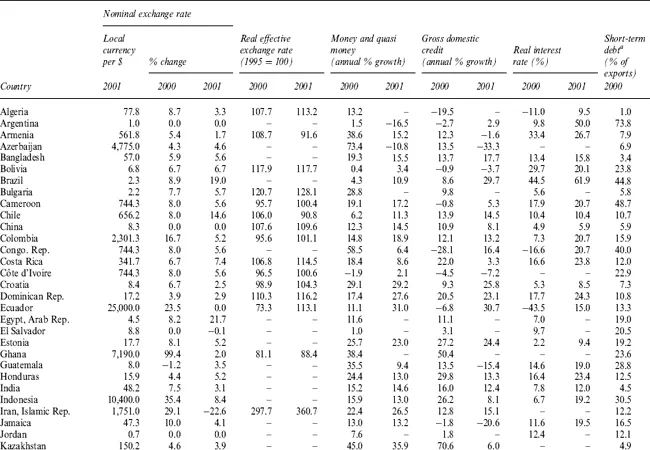

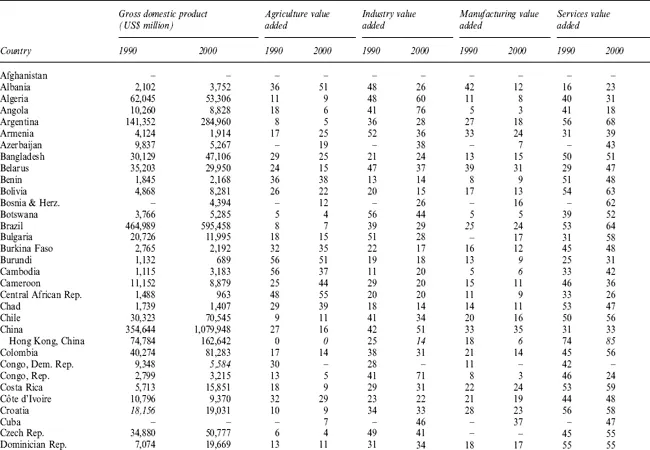

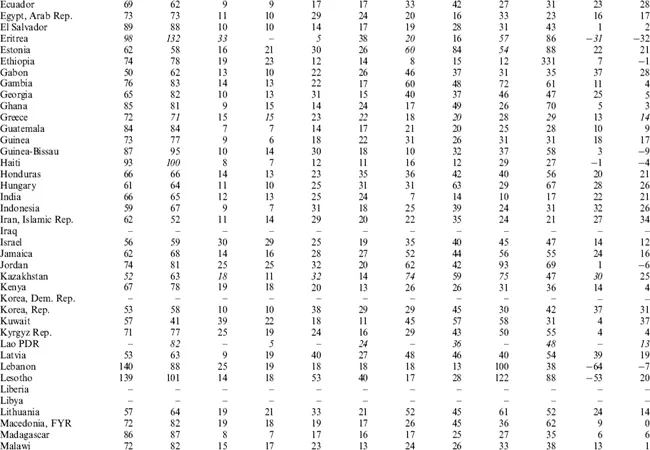

Table 1.2 Key macroeconomic indicators

Note: Data for 2001 are preliminary and may not cover the entire year. a More recent data on short-term debt are available on a Web siite maintained by the Bank for International Settlements, the International Monetary Fund, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, and the World Bank: www.oecd.org/debt.

Source: International Monetary Fund, International Financial Statistics; World Bank, Debtor Reporting System.

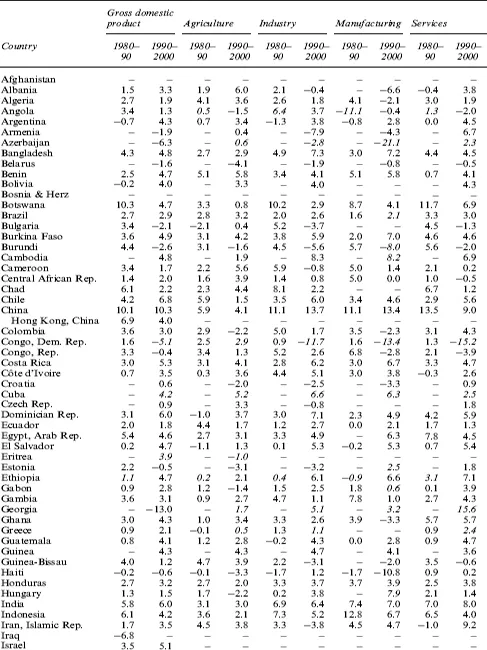

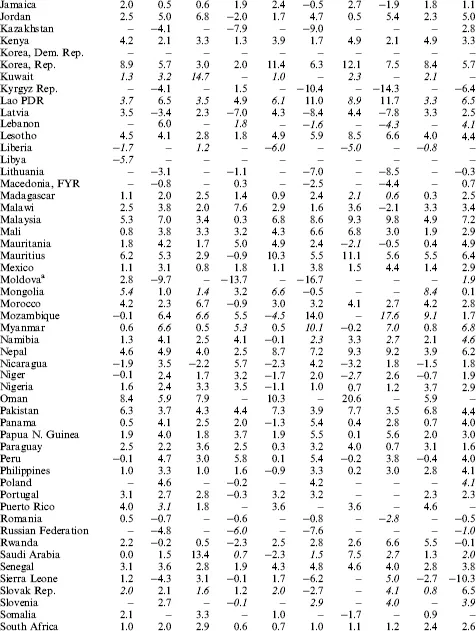

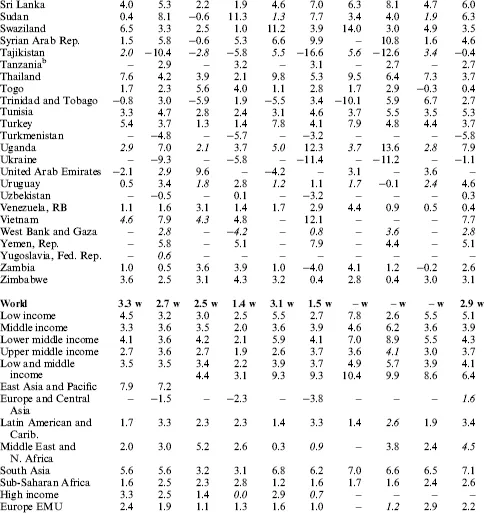

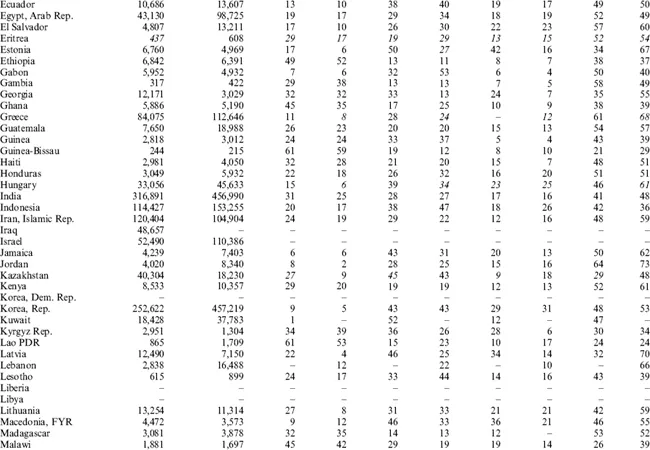

Table 1.3 Growth of output, 1980–90 and 1990–2000 (average annual %)

Notes: a Excludes data for Transnistria. b Data cover mainland Tanzania only. Italic figures indicate slightly different period.

Source: World Bank 2002.

1.2.3 Unemployment, underemployment and disguised unemployment and low productivity

Large-scale unemployment is a common feature of most LDCs. Factors like population pressure, the absence of job opportunities, either because of the low level of economic activity or because of the poor growth rate or both, the choice of techniques which are capital rather than labour intensive, education which is unrelated to economic needs, rigid wages set without much regard to the social opportunity cost of labour and lack of investment could all explain such unemployment problems. The phenomenon of underemployment noticed in many LDCs is a situation whereby the type of employment has not much relation to the qualification of the employees, wages are above the marginal productivity of labour and a large portion of labour-hours remains unused. Disguised unemployment is supposed to occur when the employment of an additional unit of labour does not add anything to production. The reason for employment could be, say, family considerations rather than profit maximization. Reliable information about actual unemployment in the LDCs is difficult to obtain, but most data suggest that the proportion of unemployment in the LDCs varies between 8 per cent and 35 per cent (Turnham and Jaegar 1971). The unemployed and the underemployed together in the LDCs would probably be about 30 per cent of the total work force (Todaro 1981). However, most data on labour utilization in the LDCs are rather weak, particularly in the rural areas. Both the quantity and quality of information are better for industrial employment which in most LDCs varies between 5 per cent and 25 per cent. Substantial difficulties are involved in the measurement of the actual level of underemployment and disguised unemployment in LDCs in the light of the production conditions and objective functions of these economies. Owing to the nature of the agricultural production cycle, work is sometimes available for six months in a year when labour shortage rather than labour surplus may be observed, particularly during the sowing and harvesting seasons in agriculture. Such seasonalities must be accounted for in the estimation of unemployment. Also, if family income or output rather than profit maximization is regarded as the objective condition, then the comparison between the marginal product of labour and wages becomes less meaningful.

Labour in the LDCs is relatively abundant in relation to capital and the productivity of labour is usually low in most LDCs in comparison with such productivity in the DCs. Such low productivity is the outcome of the paucity of capital and other resources, backward technology, lack of proper education, training and skill, and poor health and nutrition.

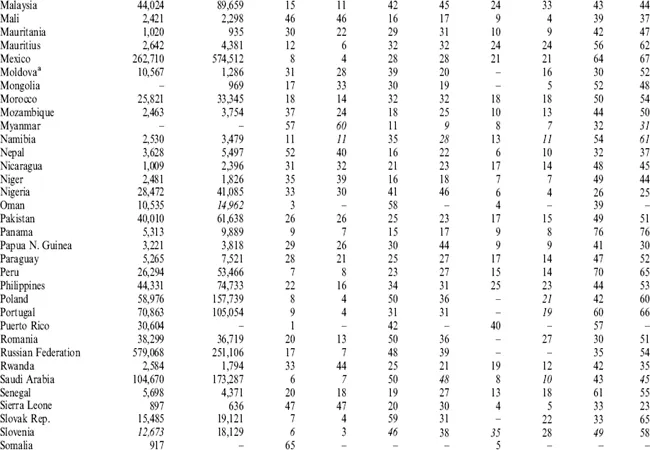

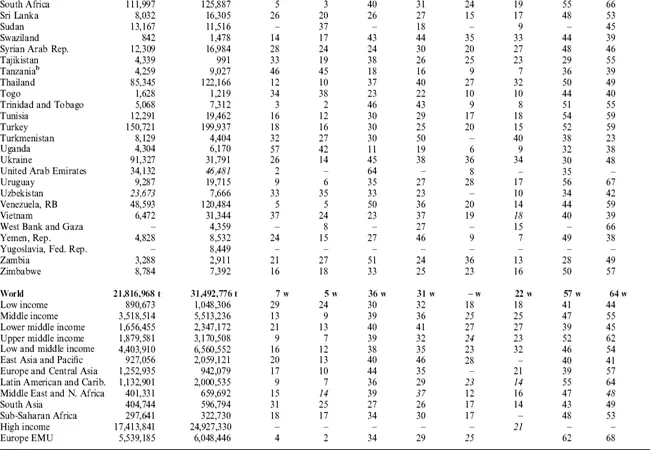

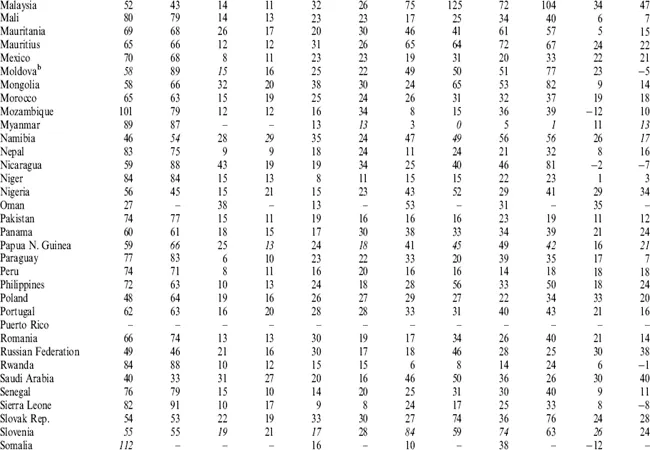

Table 1.4 Structure of output, 1990 and 2000 (% of GDP)

Notes: a Excludes data for Transnistria. b Data cover mainland Tanzania only. Italic figures indicate slightly different period.

Source: World Bank.

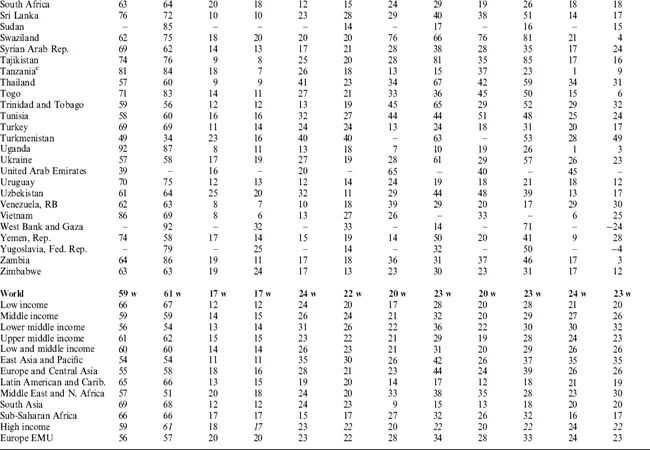

Table 1.5 Structure of demand, 1990 and 2000 (% of GDP)

Notes: a Data on general government final consumption expenditure are not available separately; they are included in household final consumption expenditure. b Excludes data for Transnistria. c Data cover mainland Tanzania only. Italic figures indicate slightly different period.

Source: World Bank.

1.2.4 Poverty

Evidence from the LDCs with regard to the level of poverty suggests that a very significant proportion of their populations earn a level of income which varies between $50 and $75 per annum at 1990 prices. This income is regarded as the minimum level for bare survival in the LDCs. It has been estimated that about 1.4 billion people, which accounts for about 35 per cent of the world's population, lived at ‘subsistence level’ by the end of 1990. This figure is staggering and more recent evidence may well suggest that the present situation might have deteriorated further. People who live on the poverty line in the LDCs usually reside in the rural areas. This raises the problem of income distribution not only among the rich and the poor countries but also within the LDCs themselves.

1.2.5 Income distribution

The pattern of income distribution within the LDCs shows considerable variation. In general, there is evidence to suggest that the pattern of income distribution tends to be more unequal in most LDCs in comparison with the DCs (Ahluwalia 1974). However, the hypothesis that the high rates of growth of income in the LDCs will always have an adverse effect on relative equality has been rejected on the basis of some evidence from the LDCs (Ahluwalia 1974). But this evidence does not alter the proposition that many LDCs experience severe inequalities in income distribution although some suffer less than others. In any case, evidence from forty-four LDCs suggest that, on average, only about 6 per cent of national income accrues to the poorest 20 per cent of the population, whereas 30–56 per cent of national income is obtained by the highest-paid 5–20 per cent of the population. In some LDCs such inequalities are extreme. For instance, in Jamaica the poorest 20 per cent of the population obtain only 2.2 per cent of national income, whereas the highest-paid 20 per cent obtain about 62 per cent of such income. In Iraq, Gabon and Colombia, the share of the poorest 20 per cent and richest 20 per cent in national income...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Introduction to Development Economics

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface to the fourth edition

- Preface to the third edition

- Preface to the second edition

- Preface to the first edition

- Acknowledgements

- 1 INTRODUCTION

- PART I The economic theory of growth and development

- PART II Investment, saving, foreign resources and industrialization in less developed countries

- PART III Sectoral development and planning

- PART IV A new deal in commodity trade?

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Introduction to Development Economics by Subrata Ghatak in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.