eBook - ePub

Political Ideologies and the Democratic Ideal

Terence Ball, Richard Dagger, Daniel I O'Neill

This is a test

- 426 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Political Ideologies and the Democratic Ideal

Terence Ball, Richard Dagger, Daniel I O'Neill

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

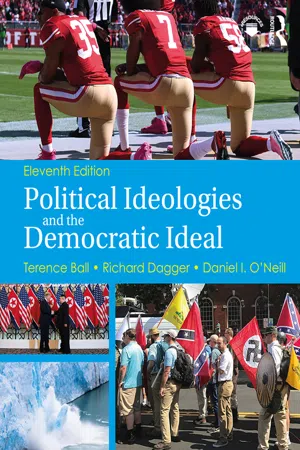

Political Ideologies and the Democratic Ideal analyzes political ideologies to help readers understand individual ideologies, and the concept of ideology, from a political science perspective. This best-selling title promotes open-mindedness and develops critical thinking skills. It covers a wide variety of political ideologies from the traditional liberalism and conservatism to recent developments in liberation politics, the emergence of the Alt-Right, and environmental politics.

NEW TO THIS EDITION

-

- Focus on the recent rise of populism and an "illiberal democracy" and how this poses a real challenge to the pillars of Western Liberal democracy;

-

- A look at early Conservatives and the idea of "natural aristocracy" with focus on the thoughts of Edmund Burke;

-

- A new discussion on whether Donald Trump is really a conservative, and if so, to what extent this is true;

-

- An expanded look at Stalinism and the apparent rebirth of "Mao Zedong thought" in China through "Xi Jinping thought";

-

- A more in-depth look at the rise of Hitler and the Nazi Party and how "myth" was crucial to legitimizing both the man and the party;

-

- New section on the history of American Fascism, from its origins to the recent emergence of the "Alt-Right";

-

- Expansion of the discussion around the recent protest movements Black Lives Matter, and #MeToo, along with the repercussions of these movements;

-

- Discussion on the obstacles facing transgender people implemented in recent years, including the bathroom laws and the ban from US military service;

-

- Account of how Donald Trump has galvanized the environmental movement like never before, through his ardent anti-environment policies and appointments;

-

- In-depth look at how the effects of climate change are increasingly turning people into "environmental migrants" and how the presence of these people has fueled far-right movements across Europe and the US;

-

- Additional photos throughout;

-

- An updated, author-written Instructor's Manual and Test Bank.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Political Ideologies and the Democratic Ideal an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Political Ideologies and the Democratic Ideal by Terence Ball, Richard Dagger, Daniel I O'Neill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Ideologies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Ideology and Democracy

Chapter 1

Ideology and Ideologies

It is what men think, that determines how they act.

John Stuart Mill, Representative Government

On a warm June evening in 2015, a prayer service was beginning at “Mother Emanuel”—the Emanuel AME church in Charleston, South Carolina—when a 21-year-old white man entered and asked the black worshipers if he could join them. They welcomed him warmly. After nearly an hour of praying with them (or perhaps pretending to), the young man took out a newly purchased pistol and began to shoot the congregants without regard to age or sex and with regard only to the color of their skin. While shouting racist epithets and slogans, he killed nine people, including the pastor, and wounded another before fleeing into the night. Arrested the next day, he told police that he had hoped to start a “race war.” The investigation that followed showed the shooter to have been a racist, a white supremacist, and a neo-Nazi sympathizer. Photos posted on his Facebook page showed him holding weapons, flanked by a Confederate flag; in another photo he is burning an American flag. He had also written a 2,500-word “manifesto” denigrating African-Americans and defending white supremacy. The FBI deemed the crime an act of “domestic terrorism.” And, far from starting his hoped-for race war, the shooter’s murderous attack backfired. The conservative Republican governor and a majority of the Republican-led state legislature agreed to remove the Confederate flag from the state capitol grounds, where it had flown for decades. In the scale of things, this is a somewhat positive outcome of a negative act. Yet his was hardly the only instance of home-grown terrorism.

The annual Boston Marathon is a joyous occasion, attracting the best runners from across the country and around the world. But the 2013 Marathon, which had begun so happily on a sunny New England morning, ended abruptly and violently at 2:49 in the afternoon as two homemade bombs exploded near the finish line, killing three onlookers and grievously injuring 264 others. The bombers, two brothers who were self-radicalized Islamists, saw themselves as defenders of their faith, engaged in a jihad, or “holy war,” against its Western, and especially its American, enemies. Violent and deadly as they were, however, the Boston Marathon bombings pale in comparison to an earlier terrorist attack.

On the morning of September 11, 2001, nineteen terrorists hijacked four American airliners bound for California from the East Coast and turned them toward targets in New York City and Washington, D.C. The hijackers crashed two of the airplanes into the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York and a third into the Pentagon in Washington. Passengers in the fourth plane, which crashed in a field in Pennsylvania, thwarted the hijackers’ attempt to fly it into another Washington target. In the end, nineteen al-Qaeda terrorists had taken the lives of nearly 3,000 innocent people. Fifteen of the terrorists came from Saudi Arabia; all nineteen professed to be devout Muslims fighting a “holy war” against Western, and particularly American, “infidels.” Condemned in the West as an appalling act of terrorism, this concerted attack was openly applauded in certain Middle Eastern countries where al-Qaeda’s now-deceased leader, Osama bin Laden, is widely regarded as a hero and its nineteen perpetrators as martyrs.

These terrorist attacks were not the first launched by radical Islamists, nor have they been the last. Since 9/11, Islamist bombings have taken more than 200 lives in Bali, more than 60 in Istanbul, more than 190 in Madrid, and more than 50 in London, to list several prominent examples. And in Syria and Iraq, ISIS (or Islamic State) has used social media to broadcast the beheadings and burnings-alive of its captives. How anyone could applaud or condone such deeds seems strange or even incomprehensible to most people in the West, just as the deeds themselves seem purely and simply evil. Evil they doubtless were. But the terrorists’ motivation and their admirers’ reasoning, however twisted, is quite comprehensible, as we shall see in the discussion of radical Islamism in Chapter 10 of this book.

Nor, as the racist church shooting in South Carolina with which we began this chapter demonstrates, should we think that all terrorists come from the Middle East or act in the name of Allah or Islam. For additional evidence to the contrary, we need only look back to 9:02 on the morning of April 19, 1995, when a powerful fertilizer bomb exploded in front of the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. One hundred sixty-eight people, including nineteen children, died in that act of terror by American neo-Nazis. More than 500 people were seriously injured. The building was so badly damaged that it had to be demolished. The death and destruction attested not only to the power of the bomb but also to the power of ideas—of neo-Nazi ideas about “racial purity,” “white power,” Jews, and other “inferior” races and ethnic groups. At least one of the bombers had learned about these ideas from a novel, The Turner Diaries (discussed at length in Chapter 7). The ideas in this novel, and in contemporary neo-Nazi ideology generally, have a long history that predates even Hitler (to whom The Turner Diaries refers as “The Great One”). This history and these ideas continue to inspire various “skinheads” and militia groups in the United States and elsewhere.

These are dramatic, and horrific, examples of the power of ideas—and specifically of those systems of ideas called ideologies. As these examples of neo-Nazi and radical Islamic terrorism attest, ideologies are sets of ideas that shape people’s thinking and actions with regard to race, nationality, the role and function of government, the relations between men and women, human responsibility for the natural environment, and many other matters. So powerful are these ideologies that Sir Isaiah Berlin (1909–1997), a distinguished philosopher and historian, concluded that there are

two factors that, above all others, have shaped human history in [the twentieth] century. One is the development of the natural sciences and technology. … The other, without doubt, consists in the great ideological storms that have altered the lives of virtually all mankind: the Russian Revolution and its aftermath—totalitarian tyrannies of both right and left and the explosions of nationalism, racism, and, in places, of religious bigotry, which, interestingly enough, not one among the most perceptive social thinkers of the nineteenth century had ever predicted.

When our descendants, in two or three centuries’ time (if mankind survives until then), come to look at our age, it is these two phenomena that will, I think, be held to be the outstanding characteristics of our century—the most demanding of explanation and analysis. But it is as well to realise that these great movements began with ideas in people’s heads: ideas about what relations between men have been, are, might be, and should be; and to realise how they came to be transformed in the name of a vision of some supreme goal in the minds of the leaders, above all of the prophets with armies at their backs.1

Acting upon various visions, these armed prophets—Lenin, Stalin, Hitler, Mussolini, Mao, and many others—left the landscape of the twentieth century littered with many millions of corpses of those they regarded as inferior or dispensable, or both. As the Russian revolutionary leader Leon Trotsky said with some understatement, “anyone desiring a quiet life has done badly to be born in the twentieth century.”2

Nor do recent events, such as 9/11 and subsequent terrorist attacks, suggest that political ideologies will fade away and leave people to lead quiet lives in the twenty-first century. We may still hope that it will prove less murderous, but so far it appears that the twenty-first century will be even more complicated politically than the twentieth was. For most of the twentieth century, the clash of three political ideologies—liberalism, communism, and fascism—dominated world politics. In World War II, the communist regime of the Soviet Union joined forces with the liberal democracies of the West to defeat the fascist alliance of Germany, Italy, and Japan. Following their triumph over fascist regimes, the communist and liberal allies soon became implacable enemies in a Cold War that lasted more than forty years. But the Cold War ended with the collapse of communism and the disintegration of the Soviet Union, and the terrifying but straightforward clash of ideologies seemed to be over. What President Ronald Reagan had called the “evil empire” of communism had all but vanished. Liberal democracy had won, and peace and prosperity seemed about to spread around the globe.

Or so it appeared for a short time in the early 1990s. In retrospect, however, the world of the Cold War has been replaced by a world no less terrifying and certainly more mystifying: a world of hot wars, fought by militant nationalists and racists bent on “ethnic cleansing”; a world of culture wars, waged by white racists and black Afrocentrists, by religious fundamentalists and secular humanists, by gay liberationists and “traditional values” groups, by feminists and antifeminists, and many others besides; and a world of suicide bombers and terrorists driven by a lethal combination of anger, humiliation, rage, and religious fervor. How are we, as students—and, more importantly, as citizens—to make sense of this new world with its bewildering clash of views and values? How are we to assess the merits of, and judge between, these very different points of view?

One way to gain the insight we need is to look closely at what the proponents of these opposing views have to say for themselves. Another is to put their words and deeds into context. Political ideologies and movements do not simply appear out of nowhere, for no apparent reason. To the contrary, they arise out of particular backgrounds and circumstances, and they typically grow out of some sense of grievance or injustice—some conviction that things are not as they could and should be. To understand the complicated political ideas and movements of the present, then, we must understand the contexts in which they have taken shape, and that requires understanding something of the past, of history. To grasp the thinking of neo-Nazi skinheads, for example, we must study the thinking of their heroes and ideological ancestors, the earlier Nazis from whom the neo- (or “new-”) Nazis take their bearings. And the same is true for any other ideology or political movement.

Every ideology and every political movement has its origins in the ideas of some earlier thinker or thinkers. As the British economist John Maynard Keynes observed in the mid-1930s, when the fascist Benito Mussolini, the Nazi Adolf Hitler, and the communist Joseph Stalin all held power,

the ideas of economists and political philosophers, both when they are right and when they are wrong, are more powerful than is commonly understood. Indeed the world is ruled by little else. Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist. Madmen in authority, who hear voices in the air, are distilling their frenzy from some academic scribbler of a few years back.3

In this book, we shall be looking not only at those “madmen in authority” but also at the “academic scribblers” whose ideas they borrowed and used—often with bloody and deadly results.

All ideologies and all political movements, then, have their roots in the past. To ignore or forget the past, as the philosopher George Santayana remarked, is to risk repeating its mistakes. If we are fortunate enough to avoid those mistakes, ignorance of the past will still keep us from understanding ourselves and the world in which we live. Our minds, our thoughts, our beliefs and attitudes—all have been forged in the fires and shaped on the anvil of earlier ideological conflicts. If we wish to act effectively and live peacefully, we need to know something about the political ideologies that have had such a profound influence on our own and other people’s political attitudes and actions.

Our aim in this book is to lay a foundation for this understanding. In this introductory chapter, our particular aim is to clarify the concept of ideology. In subsequent chapters, we will go on to examine the various ideologies that have played an important part in shaping and sometimes radically reshaping the political landscape on which we live. We will discuss liberalism, conservatism, socialism, fascism, and other ideologies in turn, and in each case, we will relate the birth and the growth of the ideology to its historical context. Arising as they do in particular historical circumstances—and typically in response to real or perceived crises—ideologies take shape and change in response to changes in those circumstances. These changes sometimes lead to perplexing results—for instance, today’s conservatives sometimes seem to have more in common with early liberals than today’s liberals do. Such perplexing results would not occur, of course, if political ideologies were fixed or frozen in place, but they are not. They respond to the changes in the world around them, including changes brought about by people acting to promote their political ideologies.

That is to say that ideologies do not react passively, like weather vanes, to every shift in the political winds. On the contrary, ideologies try to shape and direct social change. The men and women who follow and promote political ideologies—and almost all of us do this in one way or another—try to make sense of the world, to understand society and politics and economics, in order either to change it for the better or to resist changes that they think will make it worse. But to act upon the world in this way, they must react to the changes that are always taking place, including the changes brought about by rival ideologies.

Political ideologies, then, are dynamic. They do not stand still, because they cannot do what they want to do—shape the world—if they fail to adjust to changing conditions. This dynamic character of ideologies can be frustrating for anyone who wishes to understand exactly what a liberal or a conservative is, for it makes it impossible to define liberali...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- BRIEF CONTENTS

- CONTENTS

- PREFACE

- TO THE READER

- Part One Ideology and Democracy

- Part Two The Development of Political Ideologies

- Part Three Political Ideologies Today and Tomorrow

- Glossary

- Name Index

- Subject Index