Forensic Entomology

The Utility of Arthropods in Legal Investigations, Third Edition

- 620 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Forensic Entomology

The Utility of Arthropods in Legal Investigations, Third Edition

About this book

Forensic Entomology: The Utility of Arthropods in Legal Investigations, Third Edition continues in the tradition of the two best-selling prior editions and maintains its status as the single-most comprehensive book on Forensic Entomology currently available. It includes current, in-the-field best practices contributed by top professionals in the field who have advanced it through research and fieldwork over the last several decades.

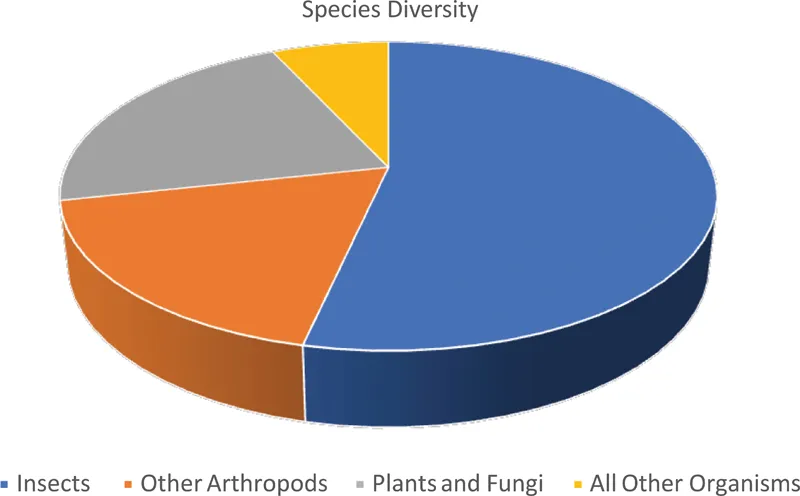

The use of entomology in crime scene and forensic investigations has never been more prevalent or useful given the work that can be done with entomological evidence. The book recounts briefly the many documented historical applications of forensic entomology over several thousand years. Chapters examine the biological foundations of insect biology and scientific underpinnings of forensic entomology, the principles that govern utilizing insects in legal and criminal investigations. The field today is diverse, both in topics studied, researched and practiced, as is the field of professionals that has expanded throughout the world to become a vital forensic sub-discipline.

Forensic Entomology, Third Edition celebrates this diversity by including several new chapters by premier experts in the field that covers such emerging topics as wildlife forensic entomology, microbiomes, urban forensic entomology, and larval insect identification, many of which are covered in depth for the first time. The book will be an invaluable reference for investigators, legal professionals, researchers, practicing and aspiring forensic entomologists, and for the many students enrolled in forensic science and entomology university programs.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

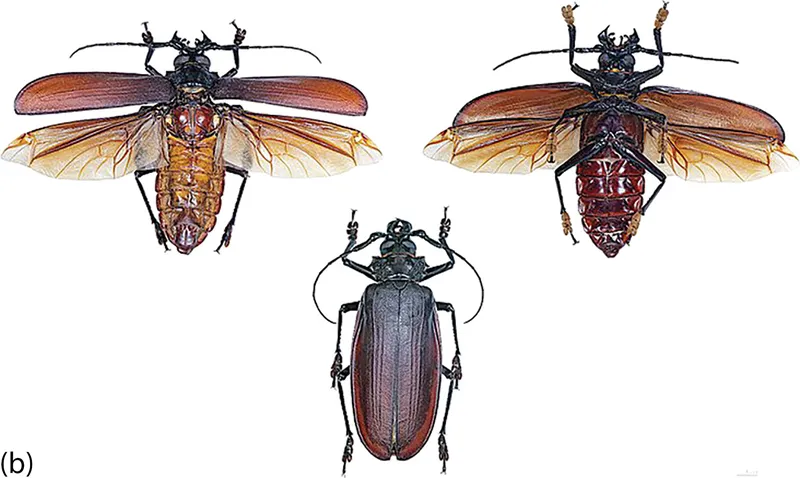

GENERAL ENTOMOLOGY AND BASIC ARTHROPOD BIOLOGY

Adrienne Brundage

INTRODUCTION

ARTHROPOD AND INSECT CLASSIFICATION

Arthropoda

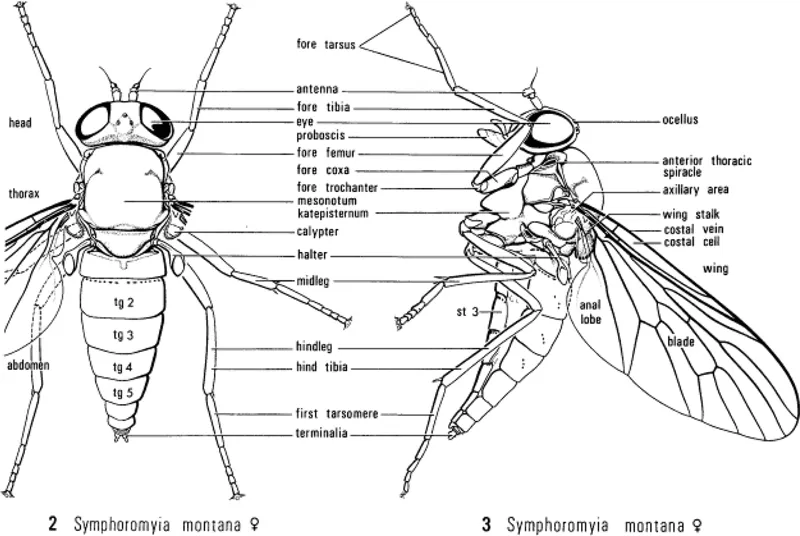

Basic Insect Anatomy

Overall Body Form

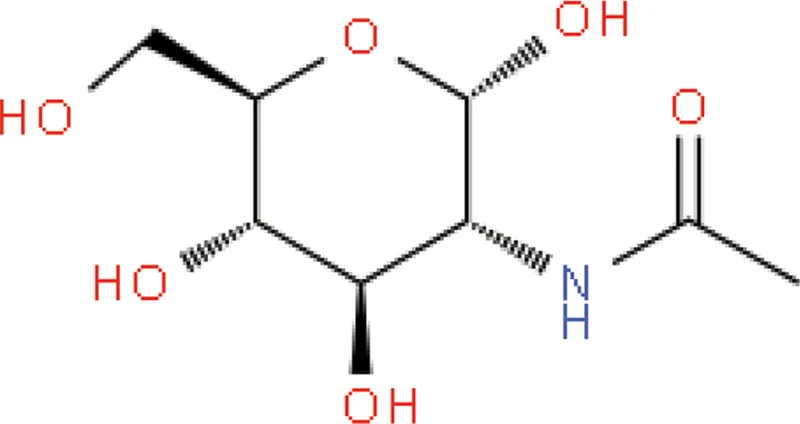

THE EXOSKELETON

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- In Memoriam

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue

- Editors

- Contributors

- Introduction: Current Perceptions and Status of Forensic Entomology

- Chapter 1 General Entomology and Basic Arthropod Biology

- Chapter 2 Insects of Forensic Importance

- Chapter 3 Entomological Evidence Collections Methods: American Board of Forensic Entomology Approved Protocols

- Chapter 4 Laboratory-Rearing of Forensic Insects

- Chapter 5 Factors That Influence Insect Succession on Carrion

- Chapter 6 Invertebrate Succession in Natural Terrestrial Environments

- Chapter 7 The Role of Aquatic Organisms in Forensic Investigations

- Chapter 8 Recovering Buried Bodies and Surface Scatter: The Associated Anthropological, Botanical, and Entomological Evidence

- Chapter 9 Estimating the Postmortem Interval

- Chapter 10 Insect Development as It Relates to Forensic Entomology

- Chapter 11 Molecular Genetic Methods for Forensic Entomology

- Chapter 12 The Soil Environment and Forensic Entomology

- Chapter 13 Advances in Entomotoxicology: Weaknesses and Strengths

- Chapter 14 Is PMI the Hypothesis or the Null Hypothesis?

- Chapter 15 The Forensic Entomologist as Expert Witness

- Chapter 16 Livestock Entomology

- Chapter 17 Ecological Theory of Community Assembly and Its Application in Forensic Entomology

- Chapter 18 Forensic Meteorology: The Science of Applying Weather Observations to Civil and Criminal Litigation

- Chapter 19 Entomological Alteration of Bloodstain Evidence

- Chapter 20 Keys to the Genera and Species of Blow Flies (Diptera: Calliphoridae) of America, North of Mexico

- Chapter 21 The Use of Entomological Evidence in Analyzing Cases of Neglect and Abuse in Humans and Animals

- Chapter 22 Acarology in Crimino-Legal Investigations: The Human Acarofauna During Life and Death

- Chapter 23 Wildlife Forensic Entomology

- Chapter 24 The Role of Decomposition Volatile Organic Compounds in Chemical Ecology

- Chapter 25 Forensic Entomology and the Microbiome

- Chapter 26 Urban Entomology

- Chapter 27 Larvae of the North American Calyptratae Flies of Forensic Importance

- Chapter 28 The Professional History of Forensic Entomology

- Chapter 29 Practical Considerations for Teaching Forensic Entomology

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app